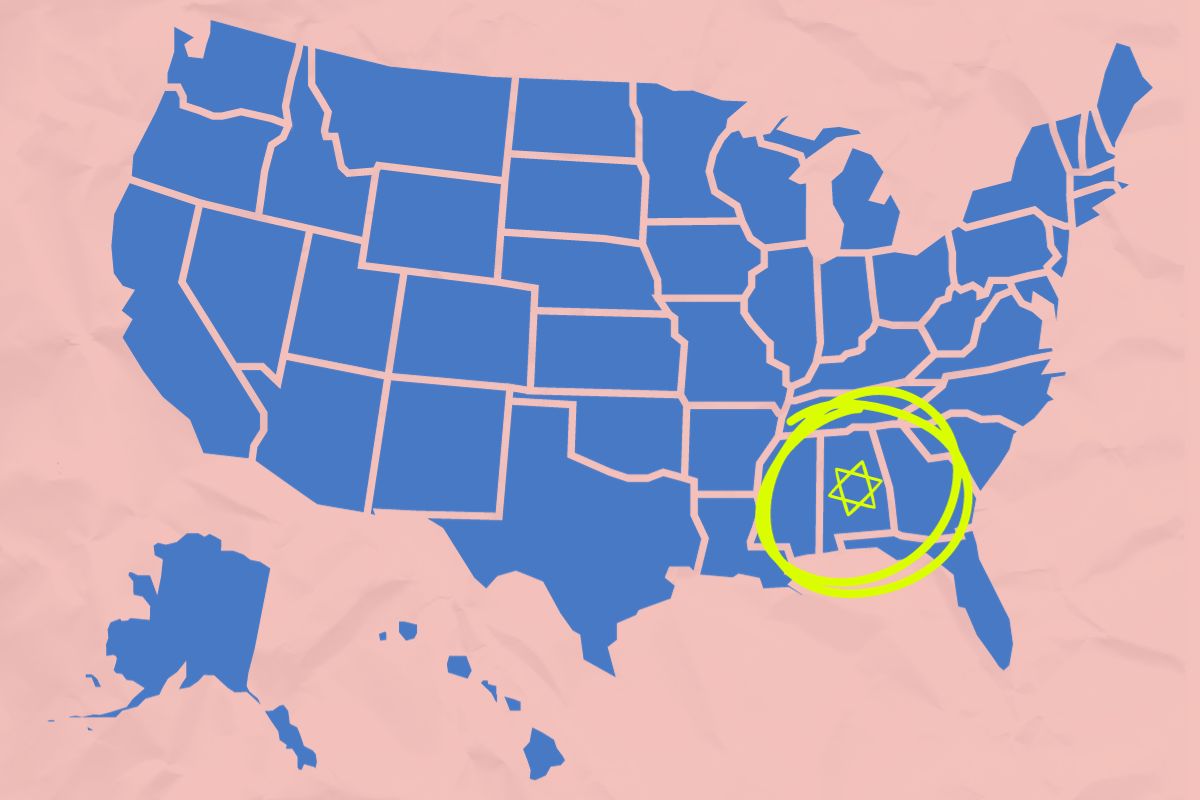

Growing up, I thought that the best way to be Jewish was the way my mother’s family did it: loudly and proudly. My mother was descended from a long line of Jews that had settled in Alabama in the 1800s, first in small towns and then larger cities.

My Southern ancestors belonged to Temple Mishkan Israel, a Selma synagogue that was established in 1870. They were also prominent members of the town, helping to establish a social club, owning businesses and becoming so ingrained in the community that a wedding dress worn by multiple generations of women in my family is now displayed in a museum there.

My mother, one of the women who wore that dress, grew up in Birmingham. Her father and uncle ran a successful business and belonged to the Jewish country club; my mother, her sisters and their cousins attended synagogue and celebrated every Jewish holiday.

When my own cousins held their joint bat mitzvah in that same synagogue, the crowd numbered in the hundreds. It was a loud and joyful occasion, one that I’d think about whenever people in Michigan, where I grew up, expressed surprise that there were Jews in Alabama. I’d remember the soaring ceiling of the sanctuary, the way our voices filled the large space as we chanted prayers, sang songs and rose and sat as one.

My own Jewish upbringing was equally observant, but quieter. My sister and I went to religious school every Saturday morning and my family attended services at the High Holidays, but none of my close friends were Jewish. Indeed, I was often the only Jewish kid in my class.

Perhaps that’s why my mother’s stories about her Jewish childhood and my cousins’ bat mitzvah made such an impression on me: because they represented being a part of a community. The people in those stories and at that celebration knew what it was to smile awkwardly when someone told you “Merry Christmas” and have to make that millisecond judgement about whether to correct them. They understood the sensation of being both within and outside of the American mainstream and what it meant to be part of a group whose existence had been threatened so often. I might have grown up in a more liberal and progressive area, but I envied my Southern family for what they had, for what they represented.

After my daughter was born in 2012, I wanted to make sure that she felt connected to her Southern Jewish heritage and extended family, even though we were raising her in Washington, D.C. My husband and I began taking her to Birmingham more often. It was on one of those trips that my aunt and I went to Kelly Ingram Park, which sits the Birmingham Civil Rights Institute and contains sculptures depicting the city’s civil rights history.

As we walked around the park, my aunt reminisced about living in Alabama during the most violent years of the Civil Rights Era, when my mother was already in college up North. She told me that while my grandparents supported the movement and believed in desegregation, they were afraid to say so publicly. “Being Jewish, especially in small towns like my grandparents were, our family knew how important equal rights were. But Mama and Daddy also knew what could happen,” my aunt said in a quiet voice, which somehow made her Southern accent stronger. I nodded, thinking of what I’d read about white Southerners that had publicly supported civil rights: lost jobs, social stigma and always the specter of a cross burning on the law.

Our conversation complicated the picture of my mother’s parents, both of whom had passed away by the time I was a year old. I’d always known of them as loving and generous people whose religion only enriched their lives. And I have no doubt that all of that is true. But now I also saw that they had had to make choices that they regretted, that they had never imagined that they would make. Choices that stayed with them for the rest of their lives.

I thought about that conversation a couple of years ago, when my family decided to put a pro-choice, pro-Judaism sign on our front lawn. It was the kind of sign that my Alabama grandparents would never have been able to put up without fear; that my family could do that two generations later felt like progress.

My aunt’s words echoed through my mind again earlier this summer, after that same sign was burned by an antisemite and I realized, in a very visceral way, that the calculations and decisions my grandparents had to make were not that far removed from my own life.

My Southern forebearers may not have always been as loud and proud about their religions as I thought when I was younger. Still, their lives have shown me how to be Jewish in a world where we’re a minority at best and targeted at worst. Some of those examples are triumphant, and some are far from that. But they have all taught me to embrace my religion and never, ever take my ability to practice it for granted.