Albert Einstein, as we all know, was one smart dude. His brilliance and IQ have long piqued people’s curiosity about how his scientific mind played out in real life. Einstein absolutely was an interesting character, but that isn’t exactly how I know him. And I do know him — sort of. I carry the same last name and share some space on the extended Einstein family tree. Being related to such an icon (we are cousins) has aroused more than just a little curiosity from others.

Both his birthday in March, and the day of his death in April, always bring world headlines and remembrances of his enormous scientific and mathematical contributions. Albert Einstein was able to significantly expand and dispute known theories of physics introduced by earlier scientists. For example, Einstein’s “photoelectric effect” was a phenomenal discovery that detailed how electrons were emitted from all matter. Among his most recognizable contributions — and least understood by the general public — was E=mc2, a formula known as the “theory of relativity,” which dealt with energy, mass, and the speed of light.

Although he had failures and setbacks along the way, Einstein’s work began to be published and recognized by the scientific community in the early 1900s. Then, as now, the name Einstein became synonymous with greatness and intellect — a great source of pride for me as one of many in his line of ancestors.

When I meet people for the first time, they are incredibly taken by the fact that my name is Einstein — even if it is wedged between my first and married name. During an introduction, I see their minds go from idle to amazed, and then I watch as they try to determine if I am pulling their leg or telling the truth. “I’ve never met an Einstein,” they invariably say. And just like that, the possibility of a stagnant conversation, or one mired in superfluous small talk instantly disappears. Instead, they fire off the first of many questions faster than Usain Bolt can run 100 meters. Are you related to Albert?

“Yes,” I promptly respond and hold my hands up as if I am drawing on an invisible chart to demonstrate where Albert and I fall on the same family tree. He is on one side and I am a little to the right. (Some of my research suggests that Albert is the husband of the niece of my second great uncle, but it is much easier to just say that we are cousins, just a touch removed.) Interestingly, some people almost always want to reach out and touch me — as if by some magic or fairy dust, the act of touching might give them an extra boost of smartness. I wish I had that power.

And then it happens: a full-on barrage of questions and a distinct shift in body language. While I was just an ordinary person a mere five minutes before we started chatting, now I am treated almost like a queen. That would be wonderful if the adulation lasted, except that it never does. It only lasts as long as I answer questions about the man himself and my relationship with him.

Do I know “the theory”? They ask, as though hearing it would change everything.

“Oh, you mean the one that starts with E=mc2 and has something to do with light beams and relativity?” I say as they nod.

“No,” I respond with a laugh. “The theory of relativity is … well … I have no idea.” At that point, I launch into some ridiculous word play about Einstein’s theory of relativity having something to do with all his relatives. A bit snarky, perhaps, but effective. Of course, one has nothing to do with the other, so everyone laughs and groans.

Honestly, I am not sure why people think I could possibly know anything about his theory based solely on my last name. He is a physicist and it took him years to figure these scientific theorems out. Meanwhile, I never even took physics in high school.

Next, people want to know if I have ever met Albert. I wish the answer was affirmative. But, no, meeting Albert in person would have been impossible for me, as he died in 1955, several years before I was born. It’s possible that my own German grandparents met him, but it’s doubtful, as our families didn’t live in the same town.

However, I once met an elderly Einstein cousin, who had lived in Germany at the same time as Albert, and he had met him when he was a boy. He said that Albert was a very nice man, amicable and actually playful with him. He said that no one in the family gave much thought to his fame but everyone was proud of his accomplishments. After my cousin moved to the United States, he, too, had people questioning him about the Einstein connection. “I always smiled,” he whispered, “and told them that smartness was in our genes. I left it at that.” It was good advice.

As the conversation continues with those who are most curious, I know the final questions will come — and they always do, never disappointing me. Am I as smart as Albert? Do I love science? And how are my math skills? Surely, no one really wants to know. But when they press for an answer, I follow my relative’s advice: I admit, with the straightest of faces, that I am as bright as Albert. Why not? I did get good grades in school and I like science. (I am also a darn good tennis player; I’ve finished a couple of triathlons; I was also a nurse and now I’m a freelance writer — none of which I believe Albert was into at all.) Then they laugh and probably wish they had never asked the question in the first place. After all, a dumb Einstein? That would be an oxymoron of epic proportions and just wouldn’t do.

I do enjoy how I can break the ice in conversations just by stating my name. At 17, I began a lifelong interest in genealogy and all things Einstein. I wanted to know where on the family tree we both landed, and since everyone else kept asking me about it, I figured I’d do the research. Now that I know, I like to embrace my Jewish namesake. It is part and parcel of my identity and I wouldn’t trade it for anything. Besides, it is rather fun. I celebrate Albert and all the Einsteins who have accomplished many great things. I am amused that people love the “wow” factor of saying they met an Einstein. Fortunately, I can oblige, even if it brings them heightened awareness and a brush with fame for just a few minutes.

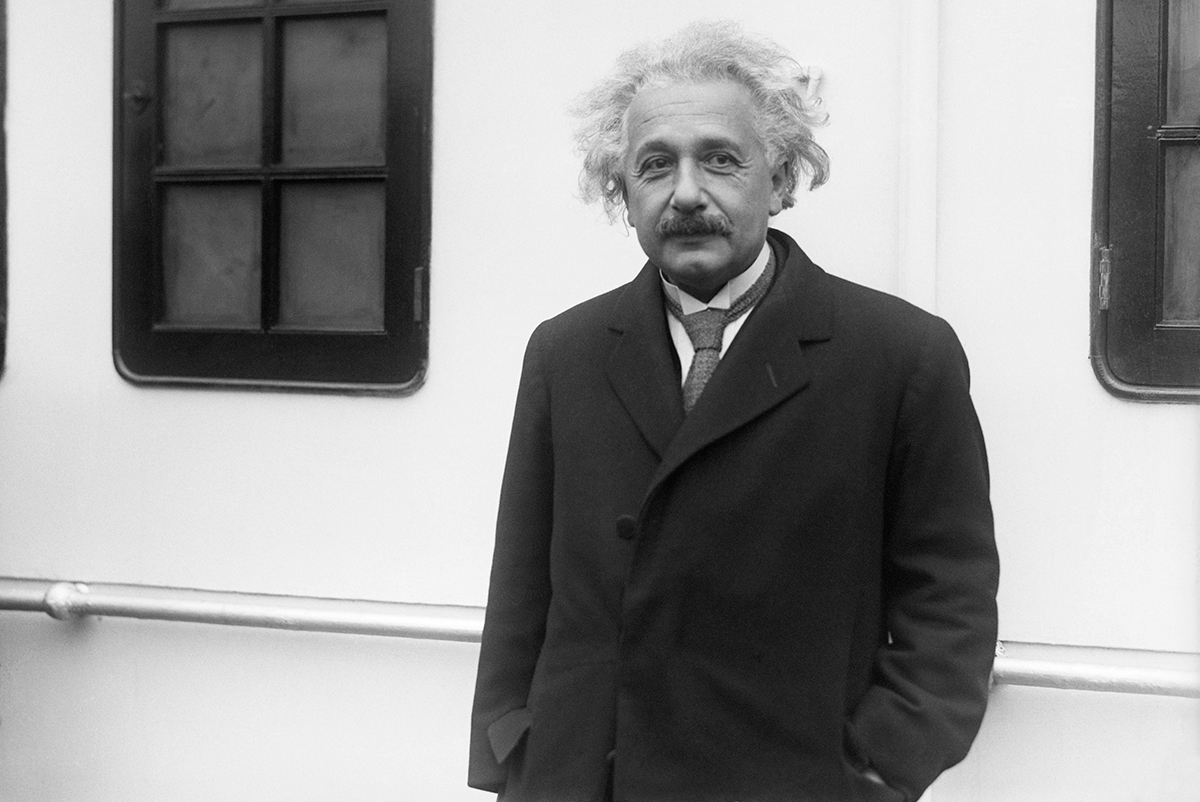

Header image by Bettmann/Contributor/Getty Images