If your kids are of a certain age, they’ve probably read Wonder, the bestselling book about Auggie Pullman, a boy born with facial differences who, after being home schooled his whole life, begins attending a school in 5th grade. It’s on our must-read list of books for kids and adults navigating disabilities and special needs — and it was made into a film in November 2017 starring Julia Roberts and Jacob Tremblay.

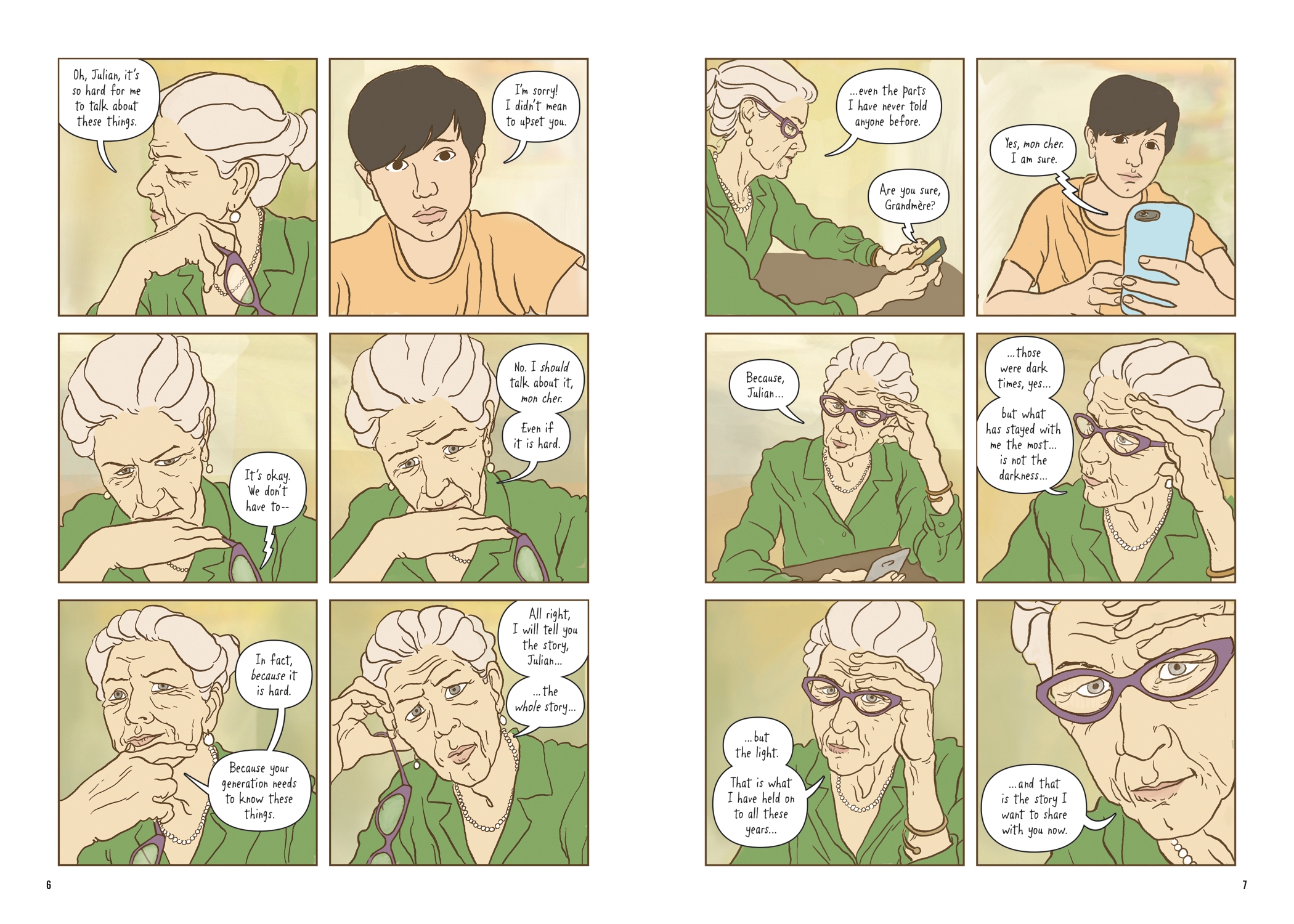

Since Wonder was published in 2012, the author, R. J. Palacio, has written a series of novels within the same universe, including Auggie and Me, a collection of three related stories. One of those stories centers on Julian, the school bully who is the antagonist in Wonder. In Auggie and Me, we learn about Grandmère, Julian’s grandmother, who was a Holocaust survivor. But we don’t get her full story — until now.

White Bird, a graphic novel by Palacio, is a deep dive into what happened to Grandmère — Sara — during World War II, and how she survived as a young Jewish girl in France.

In an interview with Kveller, Palacio explained why she decided to publish this particular story in 2019. “It’s really important for kids to have the historical context with which to [understand] what’s happening now, so that they can make the direct correlations,” she said.

In a wide-ranging conversation, Palacio talks about her husband’s Jewish family, Holocaust education, the 2016 elections, and more.

Even though you yourself are not Jewish, you write in the author’s note about your husband’s family. How much did their story influence White Bird?

It didn’t influence the actual, specific events; I was more influenced by when I [lived] in Paris for a year. But it did affect, very much, my passion for the subject. I was very close to my mother-in-law, and she lost much of her family in the Holocaust. Not that she knew them, but still I think, existentially, to have suffered that kind of profound loss, affects generations. I could not stop thinking about her while I was working on this, wishing she could have lived to have seen it, cause I think she would have loved it.

What was your research process like?

I’d always been obsessed with stories in and around the Holocaust. Because A, it’s almost impossible to imagine the suffering that happened and B, it’s even more impossible to imagine that it could have happened, and that people let it happen, that the world let it happen.

I remember reading Martin Gilbert’s book The Rightenous, which were stories about the gentiles who actually tried to shield Jews and rescue Jews, and sometimes Romani, from persecution. I’ve always been very moved by the call to goodness, and the strength it took for people to do the right thing. And those tie in very much to Wonder; Wonder is about kindness, and ultimately, standing up for your neighbors, standing up against intolerance — that’s also an extension of kindness. The kind of kindness that takes a little more courage.

Why do you think it was important to tell Sara’s story?

This is a story about a little girl who was growing up feeling completely ordinary, very much like Auggie in a lot of ways, except she really was ordinary. She had loving parents, a great school, lots of friends, and she was popular. And yet, she, like her friends, was not especially nice or kind to the little boy at school who had polio and walked with two crutches.

Ironically, this is the very boy that ends up rescuing her when Nazis come for the Jewish kids one day. As she gets to know him, she realizes that first of all, she’d been kind of a jerk, but also what they actually had in common was that they were judged for things that were beyond [their] control. There’s a whole learning process for her and evolution for her, as she realizes that she is alive because of the kindness of this boy and his family, who risk everything to shield her.

When there are so many harrowing, real-life survivor stories, why tell a fictionalized one?

Fiction is the world in which I live, and it’s important for me to tell the story within this historical context, but not try to take on a real life story. I don’t feel like I would have been able to do it, and I don’t feel like I would have been the right person to do it. I think people should tell stories about their grandparents and I hope my husband writes the story of his grandparents someday. That’s his story to tell.

Early in Sara’s story, her parents talk to her about what’s happening and the rise of Nazism. How do you talk to your kids about anti-Semitism? Do you have any tips for parents talking to their kids?

I have always taken anti-Semitism to be something that we all need to fight, whether you’re Jewish or not Jewish. It shouldn’t fall on Jewish people to remind people of the Holocaust. It shouldn’t fall on the victims of persecution to remind other people to do something to stop it. We’ve raised our kids always knowing about everything that happened. I encourage parents — I get so much that it’s a difficult subject, it’s so horrific, yet if we don’t teach our children about it, then we are relying on schools to do it, and them somehow imbibing this information from other sources which may or may not be accurate, especially nowadays.

One of the things I found very moving was the epilogue about border separations — particularly the last panel, where Julian holds up a NEVER AGAIN sign. What went into that decision?

I decided to actually do this whole story, to write White Bird, for a couple of reasons. I first introduced Grandmère and her story very briefly in “The Julian Chapter” of Auggie & Me, which was published in 2014 — before Trumpism, before we knew about border separations or anything like that.

I remember it was my husband’s Uncle Bernard, who had been a New York City principal for many years, told me that I should do it as a larger story because it was an excellent first introduction to the Holocaust for younger kids, like fourth and fifth graders. In curriculums across the country, for a lot of kids, it isn’t until the seventh or eighth grade, with the Diary of Anne Frank, that they actually first learn about the Holocaust.

In any case, I thought about [writing Grandmère’s story]… and, then, 2016 happened. And almost immediately, in January 2017 when Trump took office, there was a call for a Muslim ban, and there was a call to kick trans soldiers out of the military. And even before that, we started hearing all this anti-immigrant rhetoric. We started seeing American Nazis marching in Charlottesville. This was all happening very quickly. I could not stop thinking about it — I could not stop seeing all the dots connecting back to 1938 Europe. The rise of intolerance always leads right to anti-Semitism. If you’re a student of history, you know that that’s true.

So what brought you back to this story?

The story that Grandmère told suddenly became very relevant: The story of a little girl who becomes a refugee in her own country, who suddenly becomes illegal and loses her rights, and is facing deportation and mass roundups.

I see the direct connection between what’s happening now and what happened in the events leading up to the Holocaust in Germany and much of Europe. I thought that it was time to do what my husband’s Uncle Bernard had suggested, to tell the story of White Bird, so that kids could have a historical context with which to view what’s happening today, especially since a lot of them — and a lot of readers of Wonder who did not grow up in New York who don’t have Jewish friends, and certainly that’s a big swath of the country — may never have really heard about the Holocaust.

What do you hope kids take away from this?

It’s very important for kids to understand that they have to speak up; they have to sort of have some agency in what’s going on. I feel powerless, so I can imagine how kids must feel right now. Which is why I’m so inspired by Greta Thunberg and the Parkland kids — kids who are saying, “Well, you know what? We have to take this into our own hands because the grown-ups aren’t doing enough.” That’s what I’m hoping, for kids to get inspired and never let [something like the Holocaust] happen again.

This interview has been lightly edited for clarity. Image of R. J. Palacio in header by Heike Bogenberger.