One of the most beloved books in modern children’s literature is Maurice Sendak’s “Where the Wild Things Are.” But what exactly is a “Wild Thing,” what does Sendak’s award-winning story actually mean, and what message does it send to children?

A surprisingly Jewish one.

Maurice Sendak was born in Brooklyn, New York in June of 1928 to Jewish immigrant parents from Poland. He declared himself to be deeply affected by the Holocaust and the death of his many family members during that time. Having been introduced to the concept of mortality at such a young age, he self-describes his childhood to have been a “terrible situation.” He found comfort in books and was inspired to illustrate after seeing Walt Disney’s “Fantasia.”

“Disney was one of Maurice’s first storytelling loves,” says Patrick Rodgers, curator of the Maurice Sendak Collection at Philadelphia’s Rosenbach Museum & Library.

When it comes to storytelling, he had multiple inspirations, but one of his most notable ones came from his own father, Philip Sendak. According to Sendak, his father would often retell racy, embellished versions of the tales in the Torah. This would get him in trouble at school but helped to encourage his own wild imagination that was constantly buzzing.

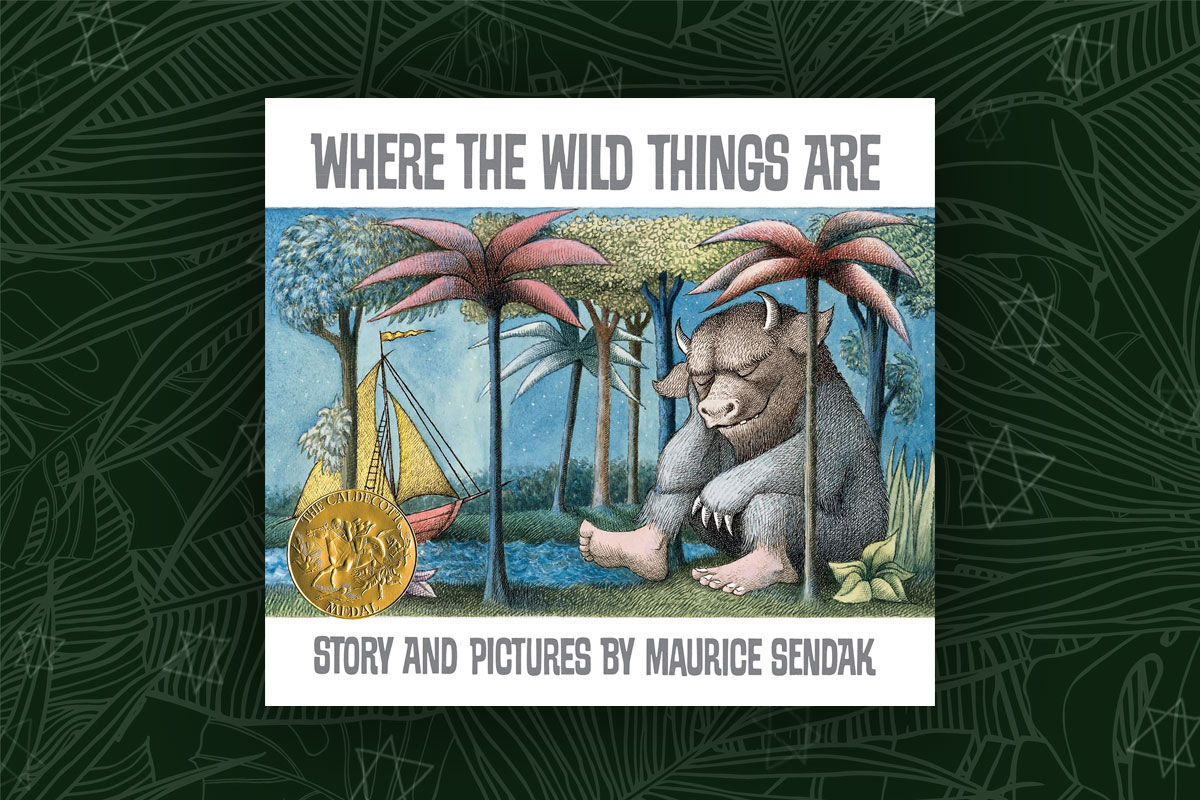

Later into his adult life is when Maurice Sendak came into global fame when he wrote and illustrated “Where the Wild Things Are” in 1963. To this day, it is a popular book to have on the shelves for children around the world. Sendak believed that children were smarter and more aware of hard emotions than many adults tend to believe. This, and his own childhood, inspired the meaning of the story.

The book stars Max, a curious and sensitive boy who feels lonely and misunderstood at home and escapes to where the “Wild Things” are. This escape leads Max to land on an island where he meets mysterious and strange creatures whose emotions are as wild and unpredictable as their actions — much like Max’s own emotions and actions.

Max was a mirror of Sendak’s own life and childhood. He was inspired by his background growing up in Brooklyn and his relationship with his parents. Much like Max, Maurice also went to bed often without supper, was rambunctious and felt like an outsider. And “Wild Thing” actually references a Yiddish term that Sendak heard growing up. When he was a child, his mother often used to call him a “vilde chaya,” meaning “wild animal” in Yiddish.

Sendak took inspiration from his relatives and based the design and drawings of the “Things” off of them, wanting to keep them personal and not look like traditional monsters. He said that he was inspired to write and draw what he saw of his relatives because they would come over every Sunday and “all say the same dumb things.” This is the reason for the iconic quote, “I’ll eat you up, I love you so!”

Using his art and books as a form of self-expression, “Where the Wild Things Are” is rooted in the experiences Sendak had growing up in the shadow of the Holocaust and with his parents who, in his words, “had problems emotionally and mentally.”

Using literature and storytelling as an escape and as a way to express your inner emotions is at the heart of the story. It comes from Sendak’s own experiences of feeling lonely and misunderstood as a child — not only by his parents but by his friends and society. Having lost family members to one of the greatest world tragedies, he didn’t have the same carefree outlook on life that his peers had. Using stories to escape this reality is not unique to Sendak, and is something most children do.

On the topic of using fantasy as a means to escape and heal, Sendak was quoted saying, “Certainly we want to protect our children from new and painful experiences that are beyond their emotional comprehension and that intensify anxiety; to a point, we can prevent premature exposure to such experiences. That is obvious. But what is just as obvious — and what is too often overlooked — is the fact that from their earliest years children live on familiar terms with disrupting emotions, fear and anxiety are an intrinsic part of their everyday lives, they continually cope with frustrations as best they can. And it is through fantasy that children achieve catharsis. It is the best means they have for taming Wild Things.”

“Where the Wild Things Are” serves as a comforting message to all children who feel “othered.” It teaches children that it’s OK to feel sad and angry. But most importantly, it is a love letter from one Jewish child to another, saying, “You are not alone, and everyone has a Wild Thing they are running from.”