As he got older, my father liked to cover his head. He was a fan of the yarmulke, not out of religious conviction, but because he said his head was always cold. There were no yarmulkes at my younger son’s wedding; like my late husband Doug, my son’s wife isn’t Jewish. My dad arrived to celebrate with a health aide, a Yankees cap and a demand.

“I want to stand,” he said. “No one wants to see a picture of an old man in a wheelchair.

My two sons, dressed in tuxedos, held him upright, the boys he helped raise, now raising him. My father could be unsteady on a good day, and this was the end of a hot August. My father grabbed my hand. “These are my boys,” he said.

Five weeks later, at 91, my father was dead.

My father always behaved like someone who didn’t plan to die, and for years I conspired with him in this fiction. I should have known better. Doug had believed the same thing about himself. He was diagnosed with brain cancer in 2001, passing away nine months later at 39. Our sons were 7 and 9.

“We have to keep you healthy for the boys,” my mother said to my father. “No more torn Achilles tendons from JCC basketball.”

To steel himself for the job, my dad gave up basketball, started riding bikes with my boys and took up sports his stickball-on-the-street pals never would have imagined.

At a resort in Pennsylvania, with my sons, my sister’s family and my parents, I watched my 70-year-old dad climb on a horse.

“Do you ride, Dad?” I asked. Dad pointed to his grandsons who were several horses ahead of him. “They do, so now I do,” he said.

He also started fishing again.

“The last time I did this was on an army break in Arkansas,” Dad said, packing up his car with the boys, tackle boxes and rods from a local hobby store. “We’ll grill some trout.”

“What do you mean, Grandpa?” my older son asked. “Daddy never let us keep the fish. We catch them, give them names, say goodbye and throw them back.”

My father also gamely watched the cartoon series my sons loved: “Courage The Cowardly Dog” and “SpongeBob SquarePants.” My boys still laugh about the time that their grandfather asked, “Why doesn’t that guy call himself Bob Sponge? Doesn’t he believe in last names? I guess you can’t expect much from a fella who lives in an underwater pineapple.”

The Caterfino boys probably wished they lived in an underwater pineapple when I told them that after their dad died, there’d be no more Christmas tree in our family room. I made a flimsy excuse about not wanting to string the lights, but Christmas had never been mine. After Doug’s death, we celebrated only in Oreland, PA, with his family. At first our home just felt empty. But as time went on, the man stepping into the void, my own dad, developed paternal traditions of his own.

“When you get taller than I am, I’ll buy you your first beer,” my father promised my younger son when he started middle school. It was a lovely sentiment that my dad followed through on.

Still, for all of us, figuring out how to move through major life experiences without the man we expected by our sides was not an easy proposition.

“You have a father, Mom,” my older son said as he was preparing for his wedding. “You don’t know what it’s like.”

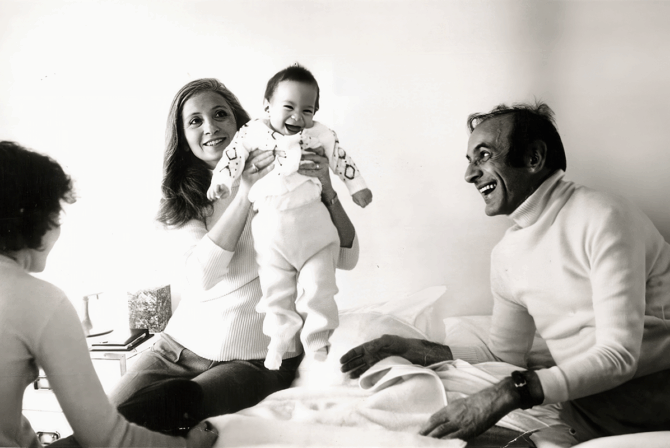

Unlike my sons, I never doubted that my dad would witness the important phases of my life. There he is, doing the hora and an Irish jig at my first wedding. Next, he’s in an NYC hospital room holding his first grandchild, my older son, in his arms. And he is sitting next to Doug and me at Sloan Kettering, watching me take notes as the oncologist describes Doug’s prognosis (a 98% chance of dying within two years). When I look up, I see Dad wiping away tears.

At this point, my sons have lived without their biological dad for 23 years. It took my own father’s death for me to be able to experience firsthand what they had to deal with in elementary school.

At my dad’s memorial service, my younger son summed up his grandfather. “When he taught my brother and me to drive, he told us to avoid the right lane because it was too slow. He thought the left lane was too fast. He said to be wary of the middle ‘cause people were merging in and out.”

After the memorial, both boys were somber. “Losing him is hard, Mom,” my older son said as his wife grabbed his hand. “Like Dad all over again.”

In the weeks after my dad’s death, I wanted to savor who he was. I spent time with old photos and found a page of his computer passwords. The one for his bank, “goddamnedpainintheass!” was classic Dad.

“Back to school,” I had said the Monday after Doug’s funeral. He’s buried in a Jewish cemetery – his choice. Now I can’t imagine how my sons marched off to school two days after shoveling dirt on their dad’s casket.

A few weeks ago, I apologized to my older son for trying to push them back to normal too fast. “Mom, it’s OK,” he said.

Somewhere along the way, my sons’ longing for their dad morphed into acceptance of the granddad who replaced him – and in the process they gained wisdom and maturity. “We know how hard this is,” both kids said after my father died.

As we prepared for the first afternoon of shiva, I watched in amazement as my sons and their wives created order out of the mishmash of family photos I’d pulled from the basement. Using my phone, they photographed the gems and set up a “screen share” on the family room television. My dad in a college graduation cap, looking uncannily like my younger son; him in a yarmulke with my mom and my sister’s family at my second wedding. And finally there is a shot of the unit my father lovingly created after Doug’s death. He’s in his early 70s, newly healed from a hip replacement, with his arm around his two bonus sons. In the photo he’s wearing a Yankees cap.