The man, the mystery, the bard Bob Dylan is the subject of the new biopic “A Complete Unknown,” starring Jewish actor Timothee Chalamet. Dylan has endorsed the movie on X and praised Chalamet, who he called by the nickname Timmy, as “a brilliant actor so I’m sure he’s going to be completely believable as me. Or a younger me. Or some other me.” He also recommended that anyone who watches the movie read the book it is based on, “Dylan Goes Electric,” by Jewish author Elijah Wald.

Dylan was born Robert Allen Zimmerman — a fact that Monica Barbaro’s Joan Baez discovers in the movie. He was given the Hebrew name Shabtai Zisl ben Avraham, grew up in an observant home among a tight-knit Jewish community in a small town in Minnesota, and went to Jewish summer camp (Camp Hertzl in Wisconsin). Yet all of that was, well, completely unknown when he burst onto the music scene as folk star Bob Dylan, and some people are still surprised to hear that the iconic musician is Jewish to this very day. Bobby Zimmerman couldn’t be an all-American folk music legend, but Bob Dylan could.

Dylan did famously become a born-again Christian in the late ’70s, and released multiple Christian-themed albums during that time, yet you can also find many traces of Dylan’s Jewish identity in his music, the early albums especially.

While recording his second album in 1963, Dylan recorded an outtake called “Hava Nagila Blues.” In it, the singer jests “here’s a foreign song I learned while in Utah,” and then slowly sings “ha-hava na-na-nagila” before yodeling to the sound of the harmonica. He could have just been fooling around in the studio, or he could have been trying to repaint the Jewish folk song as deeply American. Either way, the audio was only released in 1991 on his album of studio outtakes, “The Bootleg Series, Vol 1-3,” making clear that the song, which is part of so many Jewish celebrations, remained a part of him even after he abandoned his Jewish last name.

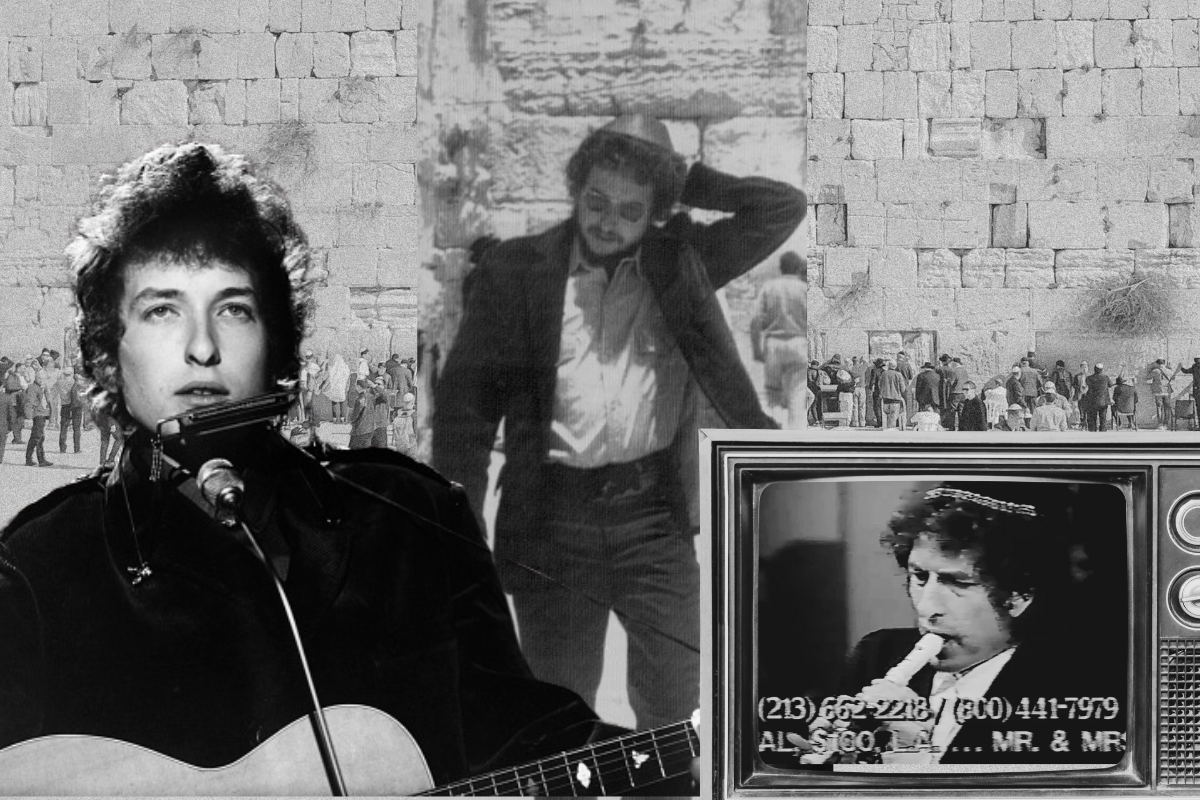

Over two and a half decades later, in 1989, at Chabad’s 25th Telethon, Dylan picked up the harmonica again to play the Jewish folk tune as his son-in-law, Peter Himmelman, an Orthodox musician married to Maria Dylan, and Harry Dean Stanton played the guitar and sang the Hebrew words. For the occasion, Dylan wore a velvet blue kippah over that signature head of curly hair. It marked what some called Dylan’s “mysterious return to Judaism.”

It’s not just “Hava Nagila” that let Dylan’s Jewish roots shine. His songs are filled with biblical allusions and words he learned in his childhood. Most famous of those perhaps is the 1974 song “Forever Young,” which starts with the first line of the Jewish priestly blessing recited over children each Shabbat — “May God bless you and keep you always” — and also features a reference to Jacob’s dream of the ladder: “May you build a ladder to the stars and climb on every rung.”

A Hebrew translation of “Forever Young” by former Israeli prime minister and current Israeli opposition leader Yair Lapid, called “Tzair Lanetzach,” was turned into a saccharine ballad by Israeli singer Rami Kleinstein, which has become a staple in Israeli bar mitzvah parties:

Bob Dylan also famously sang about Israel in his 1983 album “Infidels,” in the song “Neighborhood Bully,” with the lyrics: “Well, the neighborhood bully, he’s just one man/His enemies say he’s on their land/They got him outnumbered about a million to one/He got no place to escape to, no place to run/He’s the neighborhood bully.” Dylan has said the song was not a political one, and not meant to adopt any specific political party’s message about Israel, but just a defense of its existence. Yet the artist visited and performed in Israel on multiple occasions despite pressure to cancel his shows. In 1983, the same year he released “Infidels,” he also visited the country for a very important occasion: his eldest son Jesse’s bar mitzvah at the Western Wall. There was even a time when he considered moving to the Jewish state.

Jesse was Dylan’s oldest son with his first wife, Sara Lownds, born Shirley Marlin Noznisky to a Jewish family in Wilmington, Delaware. Dylan adopted Sara’s oldest daughter, Maria, and they had four more children, Jesse, Anna, Sam and Jakob. The couple divorced in 1977 after over a decade of marriage but continued to co-parent, and as Jakob Dylan asserted in an interview, they did a pretty great job: “My father said it himself in an interview many years ago: ‘Husband and wife failed, but mother and father didn’t’… I’ve got a life that really matters to me, and that’s because of the way I was raised. My ethics are high because my parents did a great job.”

While Dylan and most of his kids are fairly private, both Jesse and Jakob, a successful musician formerly of the band The Wallflowers, have been open about their Jewish identities. Jakob told Howard Stern that he had a bar mitzvah and considers himself Jewish regardless of his parents’ faith. Jesse, who directed a documentary about George Soros, spoke to the Times about antisemitism in 2021: “It’s hard for me to understand antisemitism,” he said. “It’s, like, really, that’s our big problem? I’m Jewish, but the Jewish thing is our big problem?” Both speak effusively of their father as affectionate and present, and Jakob told the New York Times that he idolized him as a child for all the right reasons.

While Dylan’s relationship to Judaism remains, just like the man, a bit of a mystery, it seems that there’s at least a consensus among his children that he is a pretty great dad.