Bear Bergman was a perfect parent before he had actual children.

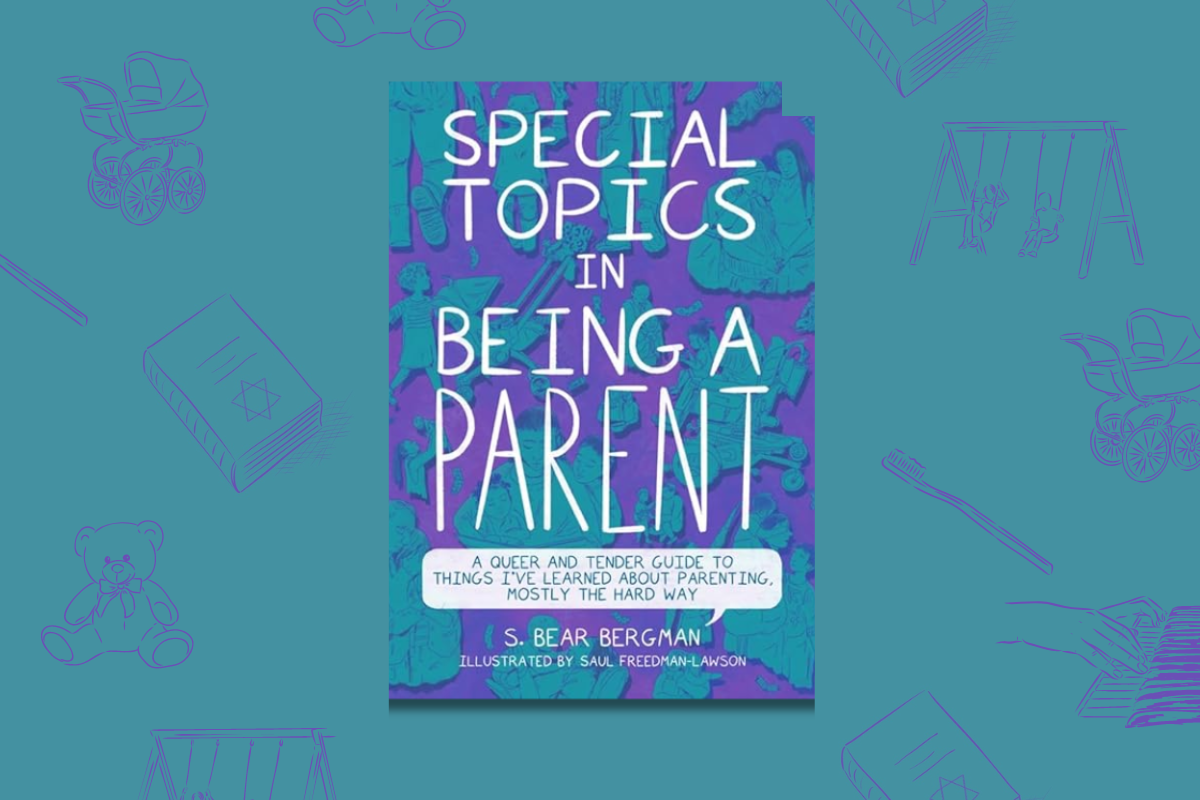

That’s the rather humbling caveat that begins his second illustrated advice book, “Special Topics in Being a Parent: A Queer and Tender Guide to Things I’ve Learned About Parenting, Mostly the Hard Way,” which will be released July 30 in Canada and August 13 in the U.S.

In it, Bergman, who has been formally giving advice for nearly a decade alongside essays, children’s books, theater works, poems and more, gives his trademark compassionate, joyful and at times vulnerable parenting advice on a variety of important topics, from how to discuss non-traditional family structures (the “family garden” as opposed to a “family tree”) to how to introduce new foods to how to deal with big life transitions, along with sweet, slice-of-life “joy recipes” along the way.

In a market saturated with advice geared towards those raising kids, Bergman found that parenting was an arena where much of the existing advice was taken as universal, and, like his previous advice work, he wanted to write a book that takes into account the larger contexts in which we live. He encourages people doing the work of parenting to take their own measure of what is important. And he infuses the Judaism that has been a part of his family’s life into his approach.

Bergman has written about Judaism and family before — in “Blood, Marriage, Wine and Glitter,” an essay collection exploring the multifaceted ways families come together, he discusses his family’s Shabbat rituals; in his performance piece “Machatunim,” he shares stories about existing in and creating queer Jewish family. In “Special Topics in Being a Parent,” Bergman dedicates a section on the Jewish concepts of “yetzer tov” (inclination towards good actions) and “yetzer hara” (inclination towards evil actions) and how they frame how he views the behavior of both parent and child.

“I think that Talmud and midrash as an intellectual grounding make a kind of parenting that is much less authoritarian and more authoritative,” he says. “I am open to argument. I don’t necessarily see it as a challenge to me as a parent. I very much value you telling kids not just what but why, and why it’s important. I want them to think about what surrounds a rule rather than just what is the rule.”

Bergman says Jewish cultural values around storytelling, food and hospitality have been important to his family, and that he’s particularly excited by the way his children feel empowered to invite people to family movie nights or other gatherings. Shabbat, both the ritual of having family dinner every week and the idea of Shabbat itself, informs his approach to parenting — whether or not you’re ready for Shabbat, it’s here, and you make it work.

“It’s not always convenient or delightful to stop and make a Shabbat dinner or do political work or do parenting tasks,” Bergman says. “Do I want to drive an hour and a quarter each way to go to the Kite Festival? Not really. But the Kite Festival is now and I can trust that if I do the thing, I will be glad to have invested the time, the feelings will come.”

As Bergman drew from his own wide network of parents and families to inform the guidance in the book, “Special Topics in Being a Parent” echoes a theme through Bergman’s work — that of interdependence and the importance of community. “I love… being able to be there for someone and also have them be there for me or us,” he says. “I lean way into that as a parent. In the moment, sometimes it’s a lot. Do I want to organize my schedule around someone else having major surgery and their children needing additional care and support? Not that much, I’ve got a lot going on. But also, yes, very much, because to me that’s at the root of all the important things that community can do and for me it feels worth it to really reach for those moments. I love the fact that my children also have very similar values about being in community because that’s how they have been raised.”

Bergman’s advice when it comes to building and sustaining that community, especially as a family? Show up, and create events and opportunities for people to participate and come together. It can be intimidating, but Bergman says it’s a lot of “putting yourself out there, over and over again.”

“I think sometimes people have a little bit of a hard time starting because you ask one time, you get one no, your batting average is zero and it feels shitty,” he says. “If you ask a lot, then some people are always going to be into it and some people are going to be and some are in the middle and that’s fine.”

Bergman’s three children are 28, 13 and 8 at the time of writing his latest book, and his own parenting journey, like everyone else’s, is full of joys and challenges. His children, he says, are interesting and thoughtful and clever, and he likes hearing about what they’re thinking (save for Pokémon-related arguments), but the greatest joy is that his children want to spend time with their parents.

“I love that they still want to be together and talk about stuff and go on road trips together and go camping together and come along on errands,” he says. “The hard things are minor in comparison. Having children is just a lot of tasks, and they’re not necessarily tasks that I want to do. It’s easy enough to let those things take up a lot of my parenting feelings if I let them because they’re so constant. I would rather have to remind my children x number of times that it’s their day to take out the trash, but remind them next to me on the couch where they are sitting with their slightly grimy socked feet on my lap reading a book, than have to hunt them down when I want them for dinner.”

To some degree, Bergman says his book is for everyone, but in particular for people who are breaking traumatic cycles or who cannot use their own parents as role models for caregiving.

“I talk to a lot of people, especially queer and trans people, who have trouble imagining themselves as parents because they didn’t feel safe and loved themselves as children,” he says. “I like the idea that in this book, there are some road maps to how to help children feel safe and loved that do not require anyone to have a specific gender or sexual orientation or relationship style.”

Bergman hopes that Jewish families and queer and trans Jewish families will read “Special Topics in Being a Parent” and feel validated and resonate with it. Citing literacy educator Rudine Sims Bishop, who first coined the idea of books being “windows, mirrors or sliding doors” to how people can see themselves or others, he hopes the book will be all three, but is especially excited for people seeking it as a mirror, who are looking for representations of themselves and their communities.

“It’s always about giving people that moment of seeing themselves reflected in a way that is loving and peaceful and positive and joyful and not always ‘your identity is a problem, your family is a problem,’” he says. “If I’ve managed that, I think I will feel satisfied with this book.”