In the face of rising antisemitism, choosing a name for your Jewish baby is a radical, and deeply personal, act. If you’re like me, you’ve had a list of potential baby names in various notebooks and devices since middle school. At first inspired by the celebrities gracing the covers of Tiger Beat or starring on reality TV, the list somehow evolved into what can only be described as a Jewish day school’s incoming class roster by the time your mid-20s hit, i.e. Ezra, Avi, Liora, Zev, Tzipporah. And if you’re like me, you’ve always secretly wished your Hebrew name was your only name, because then at least you wouldn’t need to be signified by your last initial. But also, if you’re like me, you’re thankful your name is Rebecca instead of Rivka because sometimes it’s nice to blend in.

Modern Jewish parents are presented with a nomenclator’s catch-22: to loudly proclaim your child’s Jewishness with a distinctly Jewish name, including all that comes with that, or to choose a more ethnically and religiously ambiguous legal name, in hopes of protecting your future child from the possibility of antisemitism. At its core, this conversation begs some questions: What, exactly, is a “Jewish name,” and in terms of experiencing antisemitism or, inversely, communal belonging, does either option make a difference?

As a Jewish child in suburban Pennsylvania, I was one of only a handful of Jewish kids at my public school. My brother and I were definitely the only ones from families who didn’t also celebrate Christmas. As Rebecca Cantor, I had what I lovingly called a “covert Jewish name” — a name that isn’t recognizably Jewish to most, but is instantly pegged as Jewish by a fellow tribe member. It certainly wasn’t different in any linguistic or phonetic way from the names of my Christian classmates.

Even so, I was the butt of Holocaust “jokes” by fifth grade. By junior high, I was known as “Jew” — a nickname, if you can even call it that, that equally makes me cringe and want to cry as an adult. When asked to pick up a penny from the ground during a demonstration in science class — because I was seated closest to where it fell — the class snickered.

These incidents weren’t related at all to my name. They happened because I was a proud Jew. I brought matzah to school during Passover and loudly asked for the coloring page of a menorah instead of Santa as classes slowed down in December. I wore Jewish jewelry daily and strutted around my college campus in an IDF sweatshirt purchased at the shuk, no less. Conversely, I have a friend who has an unmistakably Hebrew name, and she chooses to go by its English counterpart professionally to avoid the risk of antisemitism. According to her, it has worked.

As an adult who married into a decidedly non-Jewish last name, I am now experiencing a feeling of otherness, though mostly internally. For the first time in my life, I know Jews are unsure of my status, and though I know that doesn’t change the facts, it can be uncomfortable. There are many prominent Jewish educators doing the necessary work to challenge the perception of what it means to be Jewish — whether that’s one’s skin color, ancestry or, surely, one’s name. But as a historically closed and endogamous community, both by choice and force, it’s within our nature as Jews to look for these sometimes superficial indications of belonging. On the other hand, an intensely Jewish name could lead to feelings of isolation in larger society. Where does your family, and as follows, your child, spend more of their time: in Jewish community or secular community?

In a reality where Jewish families come in all shapes and sizes, what makes a Jewish name consequently follows suit. As interfaith families are on the rise, Jews are living in areas with smaller communities, and Jews with different ethnic backgrounds have kids, is a Jewish name so easily defined? According to some, a Jewish name is a name that appears in the Torah — though many of those names have been adopted by larger society, and thus, don’t automatically read as “Jewish.” Think: David, Aaron, Rachel, Leah, Noah. To others, Jewish names are heavily Ashkenazi-focused, which brings into the conversation the stereotypical Jewish surnames, a topic that requires an entirely separate analysis. Some Jewish cultures name after the living, some only name after the dead. Other pieces of the ever-evolving definition of a Jewish name are names of famous rabbis and scholars, Jewish leaders, biblical or historically significant places, Hebrew words or simply names that were commonly given to Jewish children during a specific decade. If these are all reasons something can be considered a Jewish name, what about simply the name of any Jewish person? There is no concrete answer, and every family is going to have their own parameters, but aren’t philosophical debates a hallmark of Jewish culture anyway?

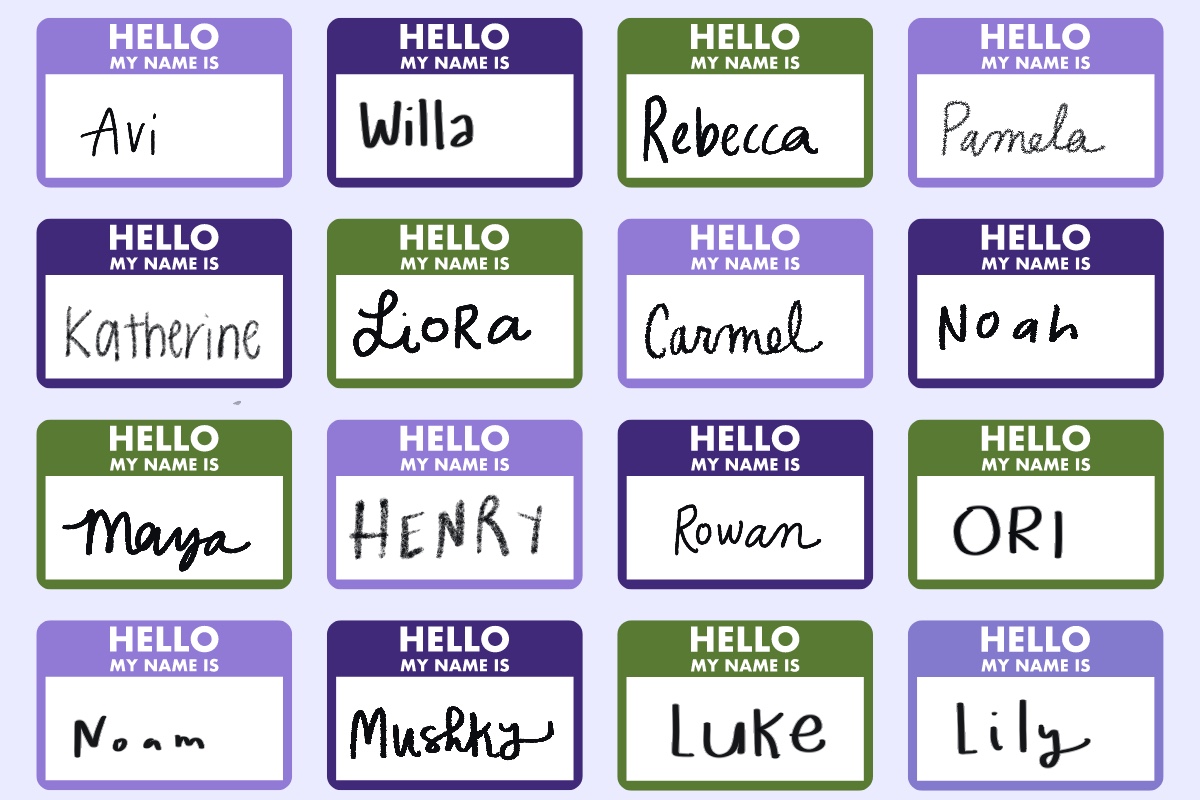

My husband and I decided to name our son Rowan Elijah — in Hebrew, Reuven Eliyahu — and Rowan will be raised to be a loud, proud mensch who will go with me to High Holiday services, bring matzah peanut butter and jellies to school during Passover, understand the miracle that it is to simply be alive and Jewish, and maybe he’ll even get his MD after he finishes law school (joking… just one of those is perfectly fine). In that way, Rowan is as Jewish as a name as they come. We hope our son doesn’t face antisemitism throughout his life, but we also know we can’t protect him from a world that can, at times, be cruel towards Jews. And even though we ended up choosing a Scottish name for our slightly red-headed toddler, we have committed to naming our next two cats Mushky and Moishe, of course.

As I lay to rest my small intellectual exercise into what it means to be Jewish and name a child, I’ve arrived at a conclusion: Every situation is unique, and a name does not a Jewish person make.