In her new novel “The Possibilities,” novelist, and one of my favorite people, Yael Goldstein-Love tells a genre-busting story about a missing baby and his heroic mother who must travel through parallel worlds in order to save him.

So often the existential crisis of new motherhood is presented as being about whether or not a woman wants to be a mom. In this book, the existential crisis is about the thorny, heady struggle to figure out how to love and care for another being, personal baggage in place. Love, even when you want to love, ain’t easy.

I spoke with Yael (my friend who I text 200 times a day) about the role maternal anxiety, particularly Jewish maternal anxiety, plays in her book. We also discuss what it was like being raised by nervous Jewish mothers — so many pu pu pus — and whether we are ones ourselves.

Elissa Strauss: In “The Possibilities,” you take Jewish maternal anxiety to places I’ve never seen. Gone is the daffy, misguided, obsessive palm-rubbing mother, whose devotion to her children metabolizes into illogical neurosis. (A caricature of course, and one almost always penned by a man.) In her place we have Hannah, a mom whose anxiety provokes deep metaphysical and psychological questioning, leading her on a journey that provides the narrative and emotional arc for the book.

Where did this idea, to turn Jewish mother overdrive into a hero’s quest, come from?

Yael Goldstein-Love: My son almost died during birth — the birth scene that begins the book is his birth pretty exactly — and for over an hour afterward they couldn’t tell me whether he would make it. He did make it, but that terrifying experience took the normal vigilance of new motherhood up several notches for me.

I felt as though my son had come too close to dying during his birth for him to be totally safe. Almost as though that other reality, in which he’d died, was also real and was threatening our cozy reality in which he was very alive, very loud, a terrible sleeper. I was falling in love with my baby while also half-believing that at any moment he’d be yanked right back out of existence. The experience could have broken me, but luckily at some point I began to find it fascinating because it let me see more clearly than I would otherwise be able how much bravery it requires to love someone in the way a parent loves a child.

Allowing yourself to love someone so fully, so protectively in the face of uncertainty, is such a deep and interesting part of the human experience. I mean talk about high stakes! And it struck me as odd that no one writes adventure stories about this kind of heroism. No one thinks of caretaking as heroic at all, except maybe in the sentimental vein of “motherhood is the hardest job in the world,” but in that vein we call motherhood heroic in order to avoid having to really think about what motherhood involves in any realistic way. I wanted to write about motherhood in a way that made it impossible to ignore what a fascinating, infinitely varied, deep human experience the transition to motherhood is, as worthy of chronicling as any traditionally male hero’s quest.

ES: While writing it, were you conscious of playing with, if not outright subverting, the concept of the nervous Jewish mom?

YGL: I wasn’t explicitly thinking about the Jewish mother trope when I wrote the first draft. But I named Hannah after the prophet Samuel’s mother, so clearly Jewish mothers were on my mind. Hannah prays for a son and promises that, if God grants her deepest desire, she’ll dedicate the child to divine service. To me this feels like a rich metaphor for how all parents have to surrender themselves to the uncertainty of bringing a person into the world and then just letting them be a person, whatever person they turn out to be, with whatever uncertain future awaits them.

Even under the best of circumstances this is hard to do, and Jewish mothers have for centuries been going about this task not under the best of circumstances, always with an eye toward whether it was safe to be a Jewish person right here, right now, whether the seeming stability of the home they were providing for their children was about to crumble into chaos and danger — exile, pogroms, worse. Our scanning and planning for all possible threats to our children is a vigilance born of generations of trauma, and what a raw deal we get in return. We hold all that fear, and we’re made into a punchline for it.

When I was working on the second draft of the book, I started to think about my character Hannah in this light. I was paying more attention to the relationship between Hannah and her husband and what might be behind their very different ways of coping with their fear for their son when the crazy events of the book start unfolding. It made me think about my own ways of coping with my maternal worry in light of my family’s long legacy of Jewish mothering, generations of mothers going back who knows how long learning again and again that the world is unsafe, that people can’t be trusted, and then passing this message down in how they mothered their kids. It also made me think about how much contempt there is in my own voice when I accuse myself of being a nervous Jewish mother. I don’t like that contempt. I wanted to interrogate it.

Once I started to think explicitly about Hannah as a Jewish mother, I did take some pleasure in turning the stereotype on its head and making a superpower out of her vigilant attention and active imagination. She’s a heroic badass because she’s a nervous Jewish mom.

ES: Do you consider yourself a nervous Jewish mom?

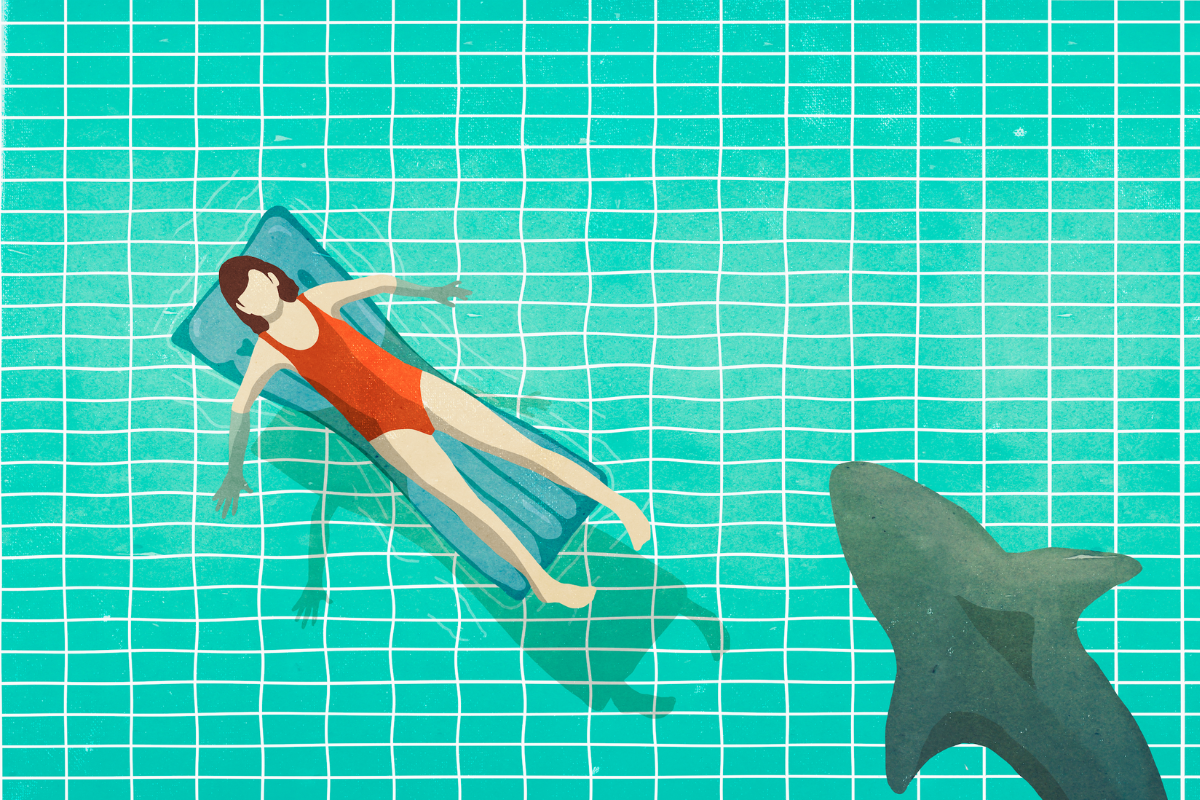

YGL: I’m laughing as I read this question, because we’re on Cape Cod right now and my 6-year-old and I just came in from swimming in the Bay and the whole time we were in the water, I was scanning for shark fins. I was trying so hard to enjoy myself and on the outside I was managing to play the part of the fun mother, but on the inside it was just sharks, sharks, sharks, sharks, sharks. You can put the yeshiva girl on Cape Cod, but . . .

So, yes, I am definitely a nervous Jewish mother in that I am always trying to anticipate the possible dangers of any situation and working through the best response. Once I have a plan in mind — e.g. punch the shark between the eyes — I can relax. Although I think there are layers to the Jewish mother trope beyond just the vigilance, right?

The Jewish mother is also supposed to be very controlling. She mistakes her feeling of danger as fact and so doesn’t let her child explore, get hurt, maybe find out that their experience of the world is quite different than hers. I try very hard not to be a Jewish mother in this way, although who knows how well I succeed.

The only aspect I don’t think fits me is the Jewish mother’s supposed ambition for her kids, her obsession with some very narrow definition of success. I think this, too, comes from the conviction that the world is dangerous and can turn on you at any time. The idea is something like, “Be successful at some lucrative or prestigious career because the economically successful and those they admire have a better chance at surviving.” Or did this particular Jewish mother trope disappear along with the housedress? I know I don’t have it, but maybe that’s because success offers no protection from the kinds of danger I fear — I’m not worried about another Holocaust, I’m worried about school shootings, climate catastrophe, that sort of thing.

But now I’m curious about you. I think of you as a very even-keeled mother, but of course one thing we have in common is that we’re both very playful mothers and that’s the side of you I see most often when we’re together with our kids. Do you consider yourself a nervous Jewish mom?

ES: My mom and grandmother, and her four sisters, and their daughters/ my aunts, all whom we spent a fair amount of time with growing up, were big time worriers (need to note that spellcheck is insisting I change this to warriors which I absolutely love in the context of this conversation!). They all moved from New York City to Los Angeles around the same time, and boy were they not having any of the earthly pleasures the Golden State offers because of the attendant dangers. I remember spending a hot summer afternoon with my grandma and her sisters at the apartment complex where they all lived and there was a big, luscious, teal-blue swimming pool beckoning all of us kids — all very good swimmers.

“No,” my great aunt Mitzi said, “there are sharks in this pool.”

“Yeah, it is very dangerous,” Shirley agreed. (Noting that sharks feature in both of our answers. So mythic. Let’s dig into that another time…)

To this day, I have an irrational fear of sharks while swimming alone in pools and, the unexpected twist, I actually cherish that fear because it is a relic of a different time and different sensibility that, overall, I miss. That fear is Esther, Shirley, Mitzi, Irene and Edna, five gals from the Bronx. And it was love. Crazy love, but love. I feel that more and more as I get older and that feeling has become more radiant as that generation of women has passed away. Some people inherit beautiful Shabbat candlesticks. I got an irrational phobia. But it’s mine! From them!

The only safe place for these women was home or a department store, and it is easy to dismiss that as evidence of their frivolity and small-mindedness, but I think the fear you outline so beautifully above has to be taken into consideration. They were unreasonable, sure, but their unreasonability was not actually that unreasonable.

Though I’m hardly living a neurotic-Jewish-caregiver-free life. My mom still keeps the fire burning. (Text me the second you land. Text me the second you get home. Call me the second you leave the doctor’s office.) Now that I have two kids of my own to worry about, I experience this worry less and less as excessive and bananas, and more and more as care.

Which brings me back to your question. Am I nervous? In response to this heavy dose of neurosis, or maybe I should say in relation to this sharks-in-the-pool neurosis, I am not that nervous in the immediate sense. I don’t looove to watch my kids taking physical risks, and am not immune to imagining the worst-case-scenario, but I would never act on it or voice it like my matriarchs (except on the side of a boat or tall building — I have mishegas (or is it?!?!) with people falling off high things). Really, though, my maternal anxiety is so much more metaphysical than existential — very in line with your book. I imagine my kids not existing. Not dying, but not existing. The thought that they couldn’t exist terrifies me. As does global warming, school shootings, etc. But those I can oddly accept as a cost of living — I’m hardly at ease with the state of affairs but it doesn’t consume on a regular basis. Whereas the miracle of life, their lives, overwhelms me with feeling sometimes. The essential fragility of people, my people. It’s a lot.

I think that if a Jewish woman can feel like this, it is good for the Jews, no? To be in a metaphysical crisis rather than an existential one…what a country! What mazel!

How did you experience Jewish maternal anxiety as a child? What did it feel like for you?

YGL: I think my mother tried very, very hard not to let her sense of the world as dangerous limit us or color our own sense of how dangerous the world actually is. My grandmother was a real piece of work in the worry and control departments, and my mom wanted so badly for us to have our own experience of the world, a more expansive and trusting one than she recognized in herself. I think in some ways she succeeded and in other ways she did not.

But I so deeply respect and appreciate the effort, which is one I’m trying my best to emulate. Living it out now with my own kid, I can see how hard she worked at it, and also how doomed the effort is on some level. Like, just to return to the shark example — here I was, letting my kid swim in the Bay despite my fears (and I want to state for the record that great white sharks were recently spotted near here, I’m not being a total Mitzi, Esther, et al.), and I was pretending to be totally cool with it, but probably he could tell that I was scanning because he’s a perceptive kid. So he was getting the same message I got from my mom and she from hers — even in moments of joy, remain vigilant to the sharp teeth lurking beneath the turquoise waters. I wish I weren’t passing along that message.

ES: I grew up with a lot of categoricals like, “Jews don’t ski.” Or, better, things like, “Jews don’t swim in bays where sharks were recently spotted.” We know we can’t follow those rules anymore, that we must leave the department store, metaphorically speaking. But it is hard. I think you are doing a great job at it!

Anyway, in addition to being a novelist and a single mom, you also practice psychotherapy and are pursuing a doctorate in clinical psychology. First, you are a marvel! Second, your interest in maternal anxiety is not limited to the realm of fiction. You are also digging into it academically, trying to better understand how maternal anxiety works and feels for women, and how different it is for all of us. What are you learning, and why is this topic so important to you?

YGL: Before I had a kid I really bought into the cultural narrative that caring for kids isn’t interesting. I’ve been amazed at how interesting it is, both intellectually and emotionally. Caring for a very needy, entirely irrational person, helping them become a person, pushes on all your hidden fears, desires and conflicts, bringing them to light in such surprising ways.

Like with any deep human experience, no two people live out any aspect of mothering in the same way. But we tend to speak of motherhood as monolithic. It’s like this. Well, no, it’s not, not for everyone. By expecting some way it is, we shut down curiosity about our own experience. I think this goes double for maternal anxiety because a worried mom is somehow regarded in our culture as one of the least interesting beings possible.

So not only is maternal worry just a fascinating part of the human experience, but also taking a stance of curiosity toward a mother’s unique experience can in itself do a world of good. When I was conducting research into maternal anxiety, my participants all had such interesting things to say about how they experienced the uncertainty of their childrens’ futures, really brilliant, original observations. But no one had ever treated their maternal worry as interesting before and so they kept surprising themselves with their own insight.

I love to imagine what it might be like if we all treated our maternal anxiety as interesting, the vast insight that might emerge.