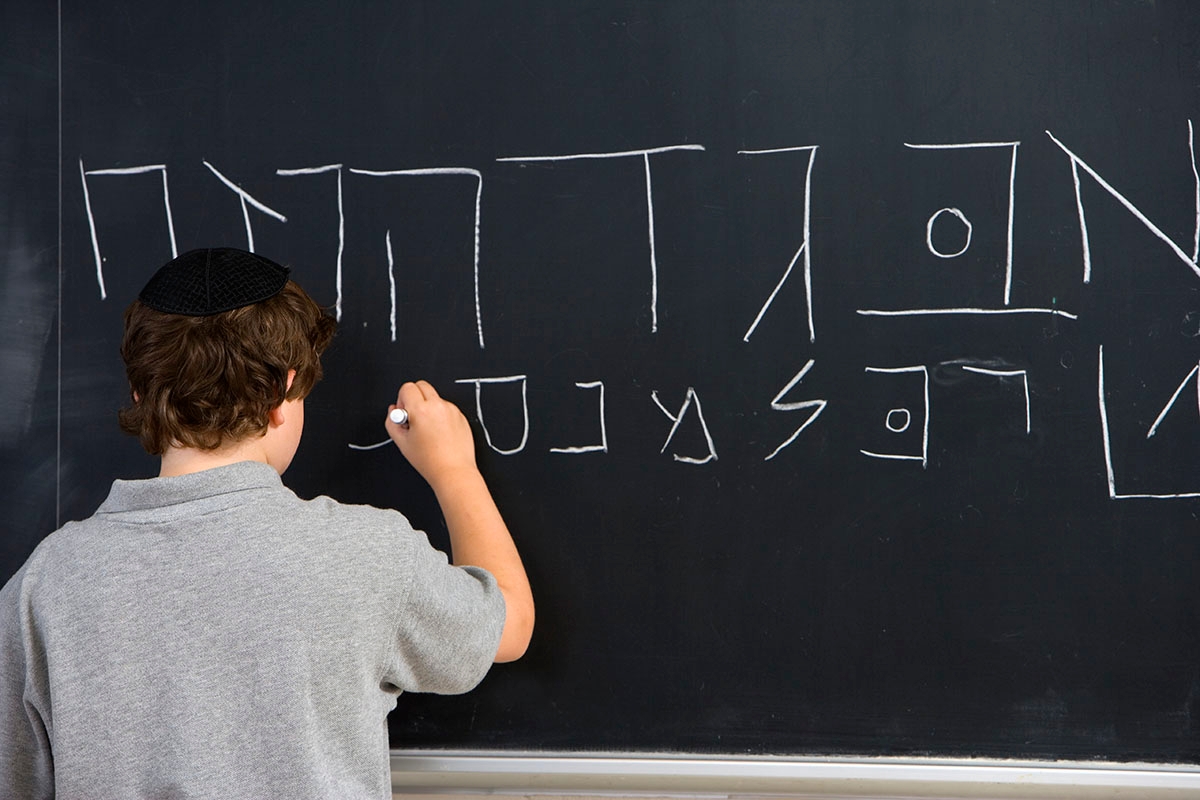

As parents, we are our kids’ teachers. Additionally, as Jewish parents, the V’ahavtah prayer enjoins us to teach God’s commandments to our children.

In Hebrew, the words for parent and teacher are linguistically related and sound almost identical: horeh and moreh, respectively. But what happens when your horeh is also your moreh? I asked my 10-year-old son, Lev, that very question recently before our first day of Hebrew school.

“Oh, God — I totally forgot you’re my teacher,” was his reply. “Crap!”

When I was growing up, my dad, a Reform rabbi, had been my Hebrew school teacher, too, in our New Jersey synagogue. I don’t remember ever having a conversation with him about it before the start of the year — or at any other time, for that matter. But I wish we had discussed how I felt about having him as my teacher, so I wanted to make sure I didn’t make the same mistake with my son. Isn’t that a microcosmic mantra for parenting?

Being an RK — a rabbi’s kid — is a lot like living under a microscope. At synagogue, everybody knows who your parents are, and if you misbehave during services or in Hebrew School, it’s a real shande, the Yiddish word for shame or disgrace.

In many ways, growing up, I never really felt like I had a dad — I had a rabbi who also happened to live in my house. True, being a TK (teacher’s kid) isn’t as all-encompassing as being an RK. Nevertheless, I didn’t want Lev to carry that extra burden of self-consciousness. So, on a recent family trip with many hours in the car to fill, I pursued the conversation further.

“Why aren’t you happy about being in my class?” I asked him.

“Because I can’t get away with everything I usually get away with in Hebrew school, like not paying attention,” he said. “But you know all that stuff and you’ll catch me all the time and I won’t be able to do anything the rest of the day.”

Given my dad’s inability to separate job and home, I suggested we should try and keep home and Hebrew school as separate as possible — a strict what happens at home stays at home, and what happens in class stays in class policy. Lev agreed that was a good idea.

I thought back to being in my dad’s class. I was always painfully self-conscious about him embarrassing me in front of my friends and classmates either by being boring, clueless or spitting when he talked, which he did a lot. I shared that with Lev and asked if he would feel embarrassed by me and, if so, by what specifically. He said yes and that the most embarrassing thing would be me giving an example of something that includes him in it.

I was incredibly grateful he shared that with me, and told him I had already thought quite a bit about that scenario. (Lord knows, I’d used things he and his little brother had done or said as examples in years past.) I promised him that I wouldn’t do that, and he seemed very relieved to hear it.

I took a different tack and asked him to name all of the good things and bad things about being in my class. For the bad things, he basically reiterated everything he’d already said. For the good things, there was only one: “being able to save all the other innocent children from the barrage of puns.” You see, I have a well-deserved reputation at Hebrew school — and, frankly, everywhere — for pun-ishing my students (and, well, I guess the people who read my articles as well?). For example, I implemented and run our synagogue’s Mensch Program, which brings our fourth and fifth graders to a local assisted living facility once a month for fun programs with our senior buddies. At the end of the year, we have a “commenschment” ceremony during which the kids are presented with certificates of “honorable menschen.”

I laughed at my son’s comment and let him know he was probably screwed there. But I threw him a bone: I told him that if this article gets published, I’d give him ten bucks for helping me. (If you’re reading this, this means I paid up.)

Without missing a beat, he countered, “I don’t work for less than $15.”

I didn’t teach him that. That one he learned from his horah/morah — aka his mother.