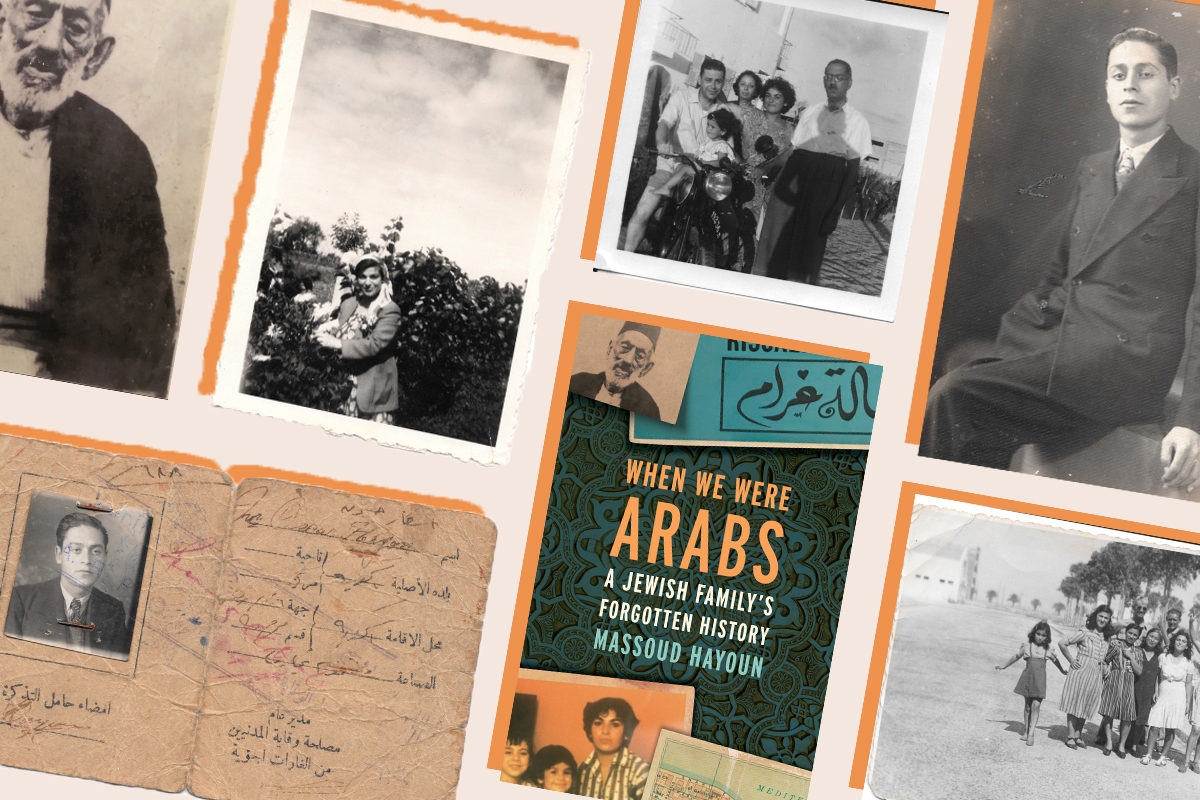

Journalist Massoud Hayoun identifies as a Jewish Arab. This identity — which is not Mizrahi, and not Sephardi — is an important claim.

“The fact that there are multiple terms to allow us to avoid the use of the term ‘Arab’ is one of the reasons why I use it,” Hayoun, 32, tells Kveller. “People who disagree, or are offended by its use, should ask themselves what about the word ‘Arab’ upsets them. And is the cause for that discomfort possibly to related to — or actually fueling — the environment of intense hatred suffered upon international Arab and Muslim communities in these times?”

Hayoun wants to reclaim the Jewish Arab identity. In When We Were Arabs: A Jewish Family’s Forgotten History, he tells the story of his family — specifically, the stories of his maternal grandparents, who raised him. His grandfather, Oscar, was born in a Moroccan and Egyptian Jewish family in Egypt; his grandmother, Daida, was from a Tunisian Jewish family in Tunis. They both left their home countries, met in France, and ended up in Los Angeles, where Hayoun grew up.

Hayoun’s memoir started as a collaboration with his grandmother. “Until her death, my grandma was a very lucid and witty person,” he says. “In our discussions, we had ample opportunity to meditate on the ways in which we were Arab, what Arabness meant, and why at various junctures we had distanced ourselves from Arabness.”

Hayoun’s grandmother, Daida (far right), with her family in a horse-drawn carriage in Tunis (Courtsey of Massoud Hayoun)

Hayoun’s family was deeply connected to its Jewish Arab heritage. There’s one passage in the book that details his bar mitzvah — replete with a belly dancer, Arabic pop music, fried Arabic food, and a shot of traditional Tunisian fig liqueur, boukha. His non-Jewish Arab friends were deeply confused.

Talking with Kveller, Hayoun reminisces on the Shabbats of his childhood. “My mother decided, out of love and deference to her father, that I would start attending Friday evening services with my grandfather when I was around 5 years old,” he says. “And then my grandfather would push me, ad nauseum, to attend Saturday morning services.”

Looking back, “I appreciate how that congregation was — the sounds of how we chanted prayers,” he says. “The chants were very meditative. Some prayers were sung to popular Arabic songs from the 40s and 50s. The foods we ate on Shabbat — frequently couscous on Friday nights and foul mudammas on Saturday — were such an expression of our identity.”

And then there was Passover. “For Jewish Egyptians, the irony is that we left Egypt — literally, not just in the spiritual sense — in recent generations,” he says. “Passover felt like our holiday, in the way that Persian friends felt a special closeness to Purim. Our Passover experience was thick inlaid with the gems of our culture. When we performed our ceremony of the Eser Makot (the 10 plagues), two women would pour wine into a bowl for every plague, and then while the rest of the guests remained silent, they would take the bowl to the bathroom, flush the wine and ululate.”

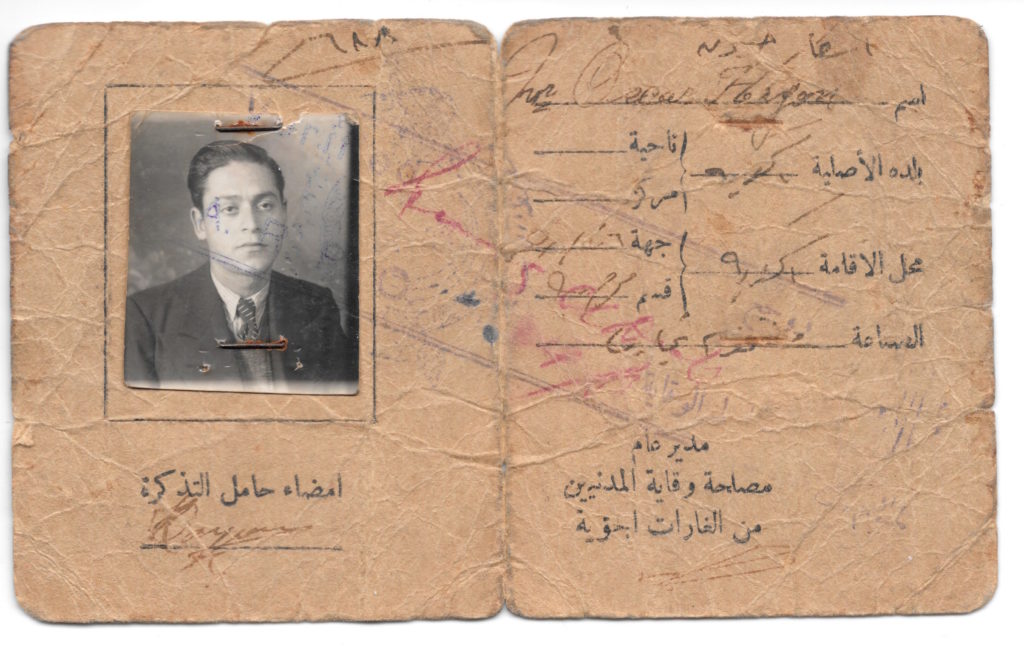

When We Were Arabs also dives into the realities of life for Jewish Arabs, especially after the formation of Israel. In 1948, Oscar — who was then working as a traveling salesman — began to hide the fact he was a Jew.

Oscar’s Egyptian ID, around World War II (Courtesy Massoud Hayoun)

“There was a disillusionment in his voice when he told stories about anti-Jewish discrimination and the dangers our family faced and then, ultimately, how he was forced to sign a contract promising never to return home.” (Which truly happened to many Jewish Egyptians.)

Still, Hayoun says he doesn’t recall his grandfather talking too much about leaving Egypt. “We never discussed any discrimination or hatred they faced. We always tried to keep it light, and then, owing to certain superstition, we never meditated for too long on death or negativity.”

“Maybe,” he adds, “on a deeper psychological level, it was too intense for my grandparents to view themselves as victims of systemic social phenomena like discrimination and racism.”

However, in writing When We Were Arabs, he dives into these systemic issues — connecting the stories of his grandparents to what was happening in the larger Arab world. Hayoun also writes about the racism his family experienced in Israel, detailing his grandfather’s arrival in Israel, where he and his family were promptly sprayed with DDT. As Hayoun writes, many new European arrivals were also sprayed with DDT, but the majority had just survived concentration camps. However, the North African and Middle Eastern Jews were simply “seen as dirty.” (His grandfather would later leave Israel for France, and then the United States.)

Allied soldiers with Daida’s family; Daida (Hayoun’s grandmother) is the second from right (Courtesy Massoud Hayoun)

Ultimately, Hayoun hopes his book will challenge readers “to look at everything — including everything they know to be true about themselves — through a decolonial lens. There’s nothing about these miserable times — the uncertainty of life under the world’s many dictatorships — that we can’t afford to revisit and improve.”

As for Jewish readers, in particular: “I want them to realize that there are populist forces in the world that would like them to have no other simultaneous identity than Jewishness. Please understand that those people don’t just disagree with the existence of Jewish Arabs — they believe that no Jew is truly American or French or Canadian. We need to rage against that.”

“After countless instances throughout history of genocide perpetrated against world Jewish communities, the international community owes us nothing less than genuine commitments to never perpetrate genocide against any people ever again.”

Header images courtesy Massoud Hayoun.