After watching “Queen of the Deuce,” out now on video on demand on Amazon and Apple TV and in select theaters, I kind of want to start a Chelly Wilson fan club.

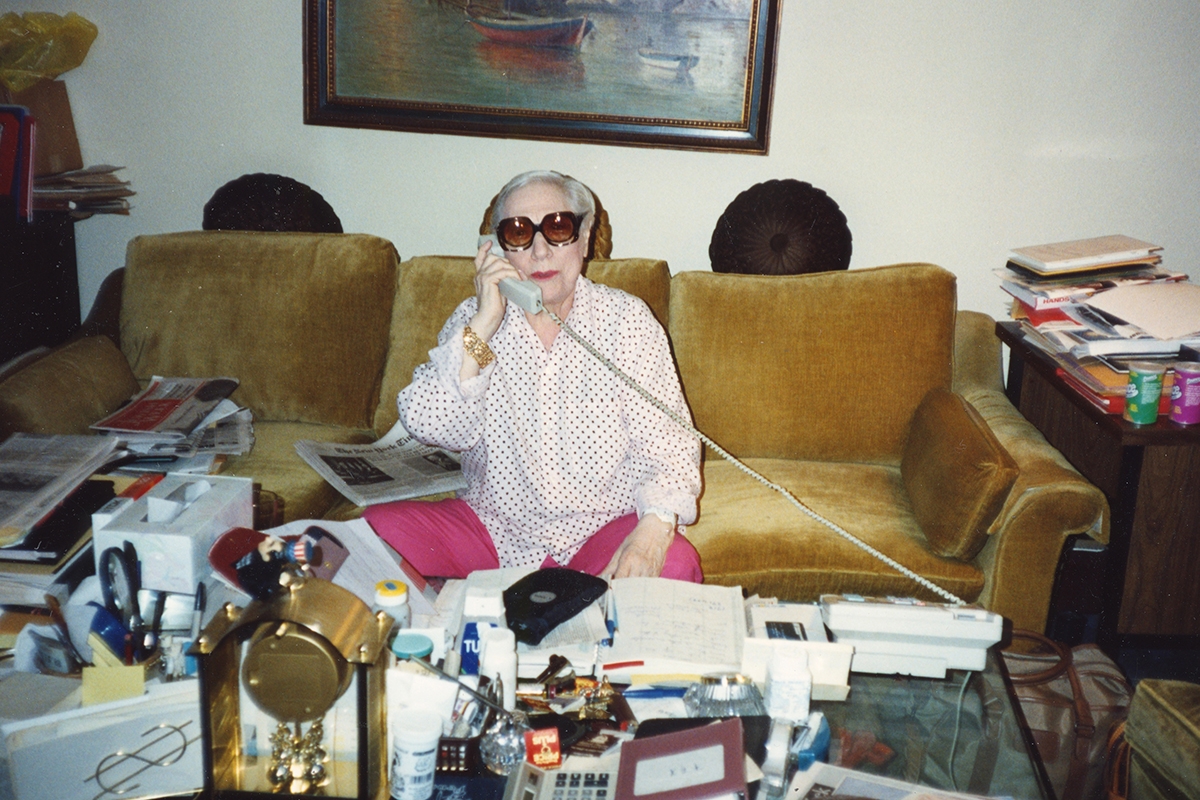

The documentary is all about Wilson, a gruff-voiced Jewish woman with short graying hair and stylish spectacles (including cat-eye glasses, which were invented by a fellow Sephardi Jewish mother) who owned an empire of porn theaters in 1970s New York City — back when the Red Light District of Times Square was called “The Deuce” — with names that all paid tribute to her Greek roots: Eros, Adonis, Venus.

Wilson was an immigrant from Thessaloniki, then known as Salonica, a hub of Jewish life destroyed by the Nazis. She lost much of her family in Auschwitz and managed to escape the country in the nick of time, on the last boat out of Athens before the war. She came to the United States with barely a word of English, started selling nuts and hot dogs on the streets, and ended up becoming a savvy, wealthy business owner. She was a married woman who had female lovers, openly queer and living with her opera singer girlfriend during a time when that was far from the norm. She was a woman who lived by the beat of her own drum and never depended on anyone.

Even before the war, Wilson didn’t fit in with her traditional Jewish family as a tomboy, a theater lover, a young girl with big career ambitions. After having two kids, she divorced the man her father made her marry, left a son with him, a daughter in the hands of a caretaker, Yaya, and worked as a businesswoman in Athens.

Wilson, who passed away in 1994, did have her own fan club of sorts. She was constantly surrounded by people — porn actors and mafiosos, musicians, lovers and admirers, queer and straight, young and old, and her family who loved her. Many of them speak in the documentary, including her daughters Paulette Pomeranz, from her first marriage back in Greece, and Bondi Walters, from her second marriage with British Jewish film producer Rex Wilson. Her grandchildren too all speak of her with a sense of awe.

“She did collect and attract a lot of people. She was like a magnet in that way,” Walters tells Kveller over Zoom.

Director Valerie Kontakos knew Wilson back in the ’70s, a fellow member of the fan club. “I always admired her. And she was always an example of what an independent woman was,” Kontakos tells Kveller. The filmmaker brings Wilson to life with such vibrancy and care in this funny, saucy, and wonderfully full of feeling documentary.

Part of what makes “Queen of the Deuce” so delightful is the animation in it, from Canadian artist Abhilasha Dewan. She animates old recordings of Wilson from an interview she held with Bondi about her life.

“I wanted Chelly to be a character in the film,” Kontankos says. “[But] there wasn’t enough home footage or anything else. I wanted to have animation to bring her to life and make her a character that was there, rather than being seen in archival material, as though it was happening [now].” The animation really gets Chelly’s energy — her chutzpah, and her relentlessness.

Chelly didn’t raise her kids with much Jewishness; in fact, Bondi didn’t even know about that aspect of her identity.

“I had no idea I was Jewish. Everything was on a need-to-know basis,” Walters, who never realized her mother was gay either, says in the documentary, sharing that she wished she knew and could have asked more questions about that part of her identity. The big Jewish story in this documentary is that of Jewish loss: the loss of her family and her community to the Holocaust, and the anger she lived with to her dying day, refusing reparations from Germany. And yet there are little trickles of her Jewish life that make their way to the documentary — a letter in Ladino, a Judeo-Spanish language; a hint of a chuppah that she put together for Bondi’s wedding at the Greek restaurant she owned, The Mykonos; and huevos haminados, Sephardic eggs, which are described as one of her favorite foods.

In hindsight, Walters tells Kveller, she knows her mother fasted every Yom Kippur. They sometimes celebrated Passover, but only much later in Bondi’s life. And despite living among Americans and Greeks most of her life, she still counted in Ladino.

“I found many letters that she had saved that that had been written to her from 1930 to 1934, and what I realized in those letters was that she came from a very Orthodox family,” Walters recounts. When Chelly’s father died, her brother was mad that she didn’t stay for the whole shiva, instead going back to Athens to work.

Wilson wasn’t a traditional maternal figure. Her grandson David Bourla calls her the most “un-grandma” like person you could ever meet. She knew she wasn’t cut out to be a mother, which is why she sent Paulette away to be cared for by her “other mother,” Yaya.

“She definitely was not, you know, the traditional mother. I always wanted somebody else’s mother when I was growing up. I wanted to come home and have the meal cooked or whatever — it was not like that in our house. But we had other wonderful adventures and people on the outside — I didn’t realize it then — always wished that they were in my family. I wanted to hide in the background and be like everybody else,” Walters says. But at the end of the day, Chelly always “did what she had to do,” even if it made her seem to her daughter as cold and unfeeling.

“I think about when she went to pick up my sister after the war,” Walter muses, “and she had to deal with getting my brother off of the boat, who was a stowaway.” Chelly’s eldest son made his way to Mandatory Palestine during the war and had to be smuggled into America by boat while her daugher Paulette was making the journey from Greece. “All she could say was ‘go home. I have to deal with this.’ I would have thought that’s a horrible thing. No hello, no kisses, no anything. Just ‘go home. I have to deal with it.’ And I would have thought oh, she didn’t care. But she did care. She knew that it was terrible but she had to do what she had to do.”

For Walters, watching the documentary now is a chance not only to relish time with her mother, but also her sister, Paulette, who recently passed away. In the documentary, she says the day she first met her sister, then a teen who barely spoke any English, was the “happiest day of my life.”

You can say Wilson was a woman of contradictions — a Jewish grandmother who owned a porn cinema empire, married to a man who was deeply in love with her while she also had affairs with women, a person who embodied the American dream while still immersed in her Greek roots, a Jewish woman who never stopped fasting on Yom Kippur and also celebrated Christmas and Orthodox Easter. A mother and grandmother who didn’t really play those parts in the way society like to envision them.

Yet the image you get of Chelly Wilson from this documentary is so warm, full and alive. The only thing that tortured her was what the Nazis had taken from her. And for both Kontakos and Walters, they hope the documentary reminds its viewers the importance of not only being strong and independent, but of being profoundly true to yourself, as Chelly was.