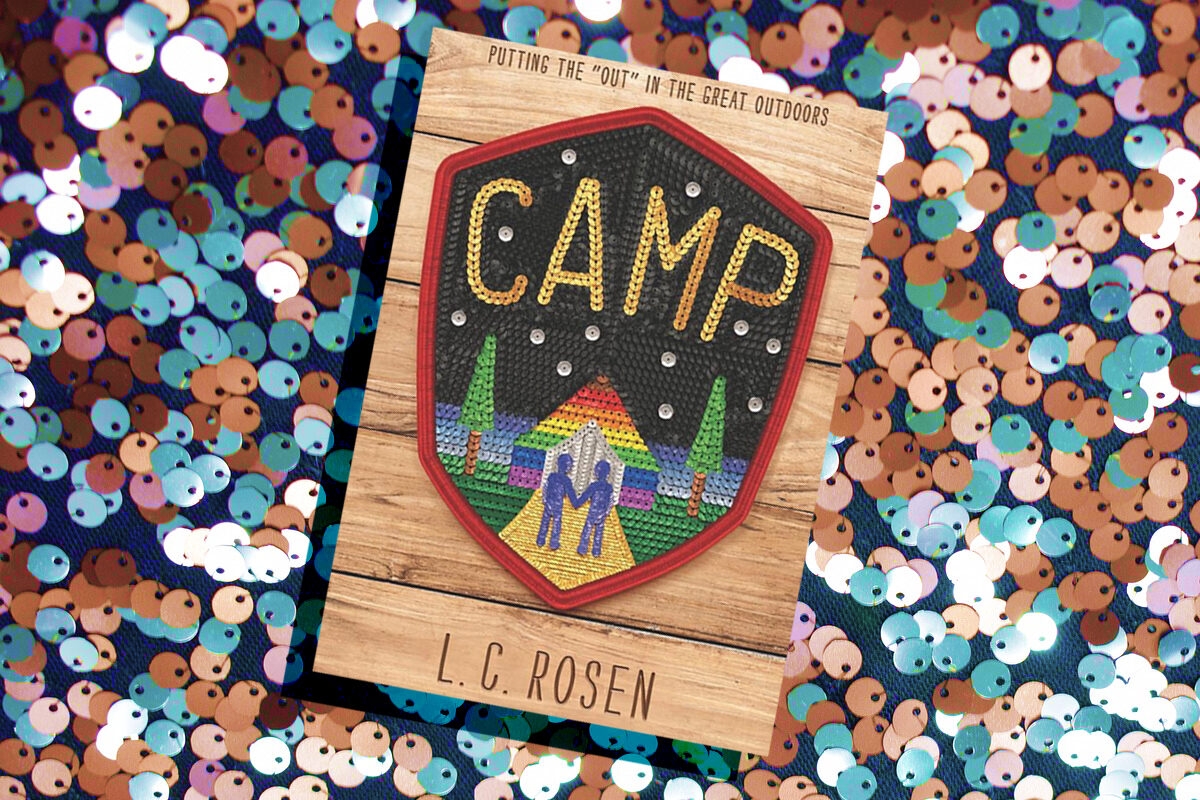

I started reading Camp by L.C. Rosen because of its truly glorious cover, which has a sequined patch featuring a silhouette of two boys walking into a rainbow-hued tent. I don’t know how anyone can resist books with sequined covers — I certainly can’t.

But as I delved into the book — or, rather, as I rapturously devoured it in one sitting — I discovered a nuanced, smart, and uplifting tale. Camp takes place at Camp Outland, an idyllic camp for queer teens where they can just be themselves. But unlike Schitt’s Creek, which imagines a world without homophobia, Camp is a tale about how toxic masculinity can creep into even the safest of spaces. Its hero is Randall “Randy” Kapplehoff, a queer, nail polish-loving Jewish theater kid who camouflages himself into “Del,” a flannel-wearing jock, in order to win over his crush, the handsome and desirable Hudson Aaronson-Lim, who also happens to be Jewish, and who, according to his online dating profile, is “masc4masc” — only attracted to masculine-acting gay men.

L.C. Rosen is the pen name of Lev Rosen, a Jewish queer writer who lives in Manhattan with his husband and very adorable cat (the proof is on Instagram). Rosen manages some pretty great storytelling feats in this refreshing YA novel, his second YA book, and his sixth published tome.

The deception plan at the heart of Camp — inspired by 1950s and 1960s Doris Day and Rock Hudson movies like Pillow Talk — could seem pretty cringe-worthy in less deft hands. But Rosen’s novel is a brilliant commentary on the “drag” everyone wears sometimes — queer people, especially — in order to fit in and to feel that we are worthy of love.

After reading this book and promptly inhaling Rosen’s other YA book, Jack of Hearts, I knew I had to ask Rosen some questions about his process. So I shot him some e-mails with approximately 5,232 questions, and he graciously and wisely answered them.

Your YA books are so wonderfully sex-positive. How did you make that choice?

I think one thing we often don’t consider is where queer kids are learning sex from. Even in liberal schools, sex ed barely touches on queer stuff. Because of that, queer kids often turn to porn and expect that to be a reality. I have no problem with ethically made porn, but it’s fantasy, not reality. If you think the first time you have sex is going to be like a porno, you are going to come out disappointed — not just in the sex, but probably in yourself. Queer kids need to see healthy, realistic sex scenes and also need to get their sex ed from somewhere. I tried to do that in both Jack of Hearts and Camp.

What was the most challenging part of writing Camp?

Well, first of all, there’s the plan: Randy’s plan to give himself a butch makeover and pretend to be someone else is, of course, terrible. It’s a terrible plan and all his friends tell him as much, but I have to make the reader willing to believe that Randy thinks it will work. That was difficult. The other part was Hudson — he’s built up into this dream man in Randy’s mind, but all his friends are telling him he’s not worth it. That was a difficult dissonance to maneuver, but it has to do with this one conversation they had when they were younger, which Hudson has forgotten, where he essentially tells Randy that he should be himself. That’s something no one has told Randy before that moment, and even if Hudson doesn’t mean it quite how Randy interprets it, it makes Randy feel powerful.

Is there a reason why you chose to center this book around Jewish characters?

Well, part of it is because I’m Jewish myself, and while I value that culture and that part of my identity, I’ve never been super Jewish in any sense, so I always like to show characters who have my kind of casual Judaism — an important part of our identity, but not a religion, exactly. The other part of it is because I actually went to a Conservative Jewish summer camp — where I got the bulk of the homophobia I got growing up — and so summer camp is a very Jewish thing to me.

What was your Jewish upbringing like, and what does being Jewish mean to you?

So my family wasn’t part of a synagogue until I was like 11, and my folks were like “oh, gotta get him bar mitzvahed” and so they joined the nearby synagogue, which was Orthodox. This was right around the time I was coming to terms with my sexuality, too, so there’s a lot going on, but we were very Reform Jews going to an Orthodox synagogue, which was all kinds of culture shock.

I went from a very non-religious, cultural Judaism to the rabbi preaching that homosexuals’ names wouldn’t be written in the book of life on Yom Kippur… It was like living in two worlds a lot of the time, and one of those worlds very clearly didn’t want me if I was queer, which I am, so I turned away from it as quickly as I could. I stopped going to synagogue. I haven’t been in years, because to me, the religion of Judaism is one that is homophobic. My parents go to a Reform synagogue now, much more welcoming, fine with my being gay, and I know the community has become much more welcoming overall these past years. But it’s hard to reconcile this new face of Judaism with what I experienced.

It honestly sounds like the Jewish summer camp you went to was the opposite of Camp Outland — did you feel like you had to be in “drag” to attend summer camp? What do you think Jewish camps can do to be more inclusive spaces?

I was actually very out at camp. That’s why I got so much of the homophobia. I think it was me challenging them. I was already the weird kid from NYC (all the other kids were from Connecticut), people already looked at me oddly, so coming out was me being like, “Think that was weird, get a load of this!” And I don’t want to say it was all bad — I have some great friends from that camp, people who stood up to the kids (and sometimes counselors) who called me “fag” regularly, people who had no problem with who I was.

In fact, I worked there. For several years. That was where the homophobia got more insidious — I was pulled aside to make sure I never mentioned my sexuality to my campers. I wore rainbows for pride once and when a camper asked why my boss leaped in and said “he likes them” before I could answer. They were afraid if it got out there was a queer counselor (and usually there was more than one), then they would have trouble with their parents.

I imagine Jewish camps can be more inclusive by letting queer people just exist. Not hiding us because our queerness makes us dangerous. Who was I dangerous to? The kids? The parents? The idea of what a Jew is? I was never sure. I just knew I was dangerous or that they were ashamed of me, and it was because I was queer.

Camp is about to be turned into a movie, congratulations! I love that Kit Williamson, who is a queer creator, is working on this project. Do you feel like that’s important?

Having an all-queer team (the producer, Dan Jinks, is also queer) is part of why I went with them. I was approached by other producers as well, but they were straight and, talking with Dan and Kit, they really understood the book, the importance of the book, and I think that that’s because they’re queer. And of course, having a queer voice to interpret my queer voice, that’s so important, because I know he’s seeing my story as his story, a story for people like us. Which isn’t to say straight people won’t love it (I love plenty of books about straight people), but that the first audience we have in mind is going to be queer folks.

Do you have any favorite Jewish LGBTQIA+ fiction?

It’s a Whole Spiel, the anthology edited by Katherine Locke and Laura Silverman. It’s a collection of Jewish stories, a few of them queer, including a summer camp one I actually avoided reading when it came out because I didn’t want it in my head when I was writing Camp. But it’s a great and diverse group of Jewish voices.

What are you hoping that people will take from this book, especially young queer readers?

That there’s no right way to be queer, and anyone who tells you as much is (intentionally or not) hurting you. That masc and femme are both types of drag, and you should be able to pick one, the other, or some combination of the two to dress yourself in any day. That just because straight kids will often see you as just the queer kid doesn’t mean you can’t be some other kind of kid on top of that — jock, nerd, theater kid, goth, whatever. You get to try on all these identities, same as the straight kids do, and take the parts of them you like the best to assemble who you want to be. You get to be whoever you want to be. Don’t let anyone tell you you don’t. But also — and this is important for teen readers — be who you need to be to keep yourself safe, too. You can keep who you are like a secret inside if you need to. That’s one special talent all queer people have.