When Sonja Sharp was 29 and pregnant with her first child, she made an appointment with an obstetrician her friends had recommended. But that doctor took one look at the expectant mother’s chart and asked her to leave. “Not ‘congratulations,’ no ‘I’m sorry,’” Sharp recalled. “She said, ‘You are a liability. We cannot see you. There is the door. Goodbye.’”

Sharp quickly realized that the Upper West Side practice was closed to her because, having suffered a spinal cord injury when she was a child, she is disabled. She went on to receive prenatal care at a practice specializing in high-risk pregnancies and had a mostly positive experience. “But I was continuously surprised that there was always testing that I didn’t really consent to,” she said, adding that nobody there talked to her about how she would deliver until she was 30 weeks along.

Six years on, Sharp is a staff writer at the Los Angeles Times and pregnant with her second child. She recently published groundbreaking reporting about the medical and social biases that pregnant people with physical, intellectual and sensory disabilities face. For example, they may be refused prenatal care, questioned about their ability to be caregivers, or faced with intimate questions about their sex lives.

Sharp, 35, an observant Jew who is active in the L.A. Jewish community, spoke with Kveller about the misconceptions people have (and vocalize) about disabled bodies, confronting limitations — every parent has them! — and how communities can better support all families.

This interview has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

Even before you were turned away at that first obstetrician’s office, what messages had you absorbed about mothers with disabilities?

It starts before puberty. You receive a lot of messages about whether or not you’re pretty, whether or not anyone would be interested in you, if that interest is safe or if it can ever be genuine. I have an identical twin sister who is not disabled, and nobody ever asked my sister whether she’s going to become a mother. It was expected.

And for you?

For me, all these questions came out: Can your body do that? Why would you want to be a mother? How are you going to take care of yourself and the baby? There are a lot of fears that even well-meaning, caring family bring to us as disabled women.

I would say two things, from my own experience and from my reporting: 1. Pregnancy is risky for everyone and 2. Many disabled women go into it with their eyes open, knowing I could lose some function for a period of time. I could lose some function permanently. It could be very difficult on my body and I’m willing to do it — and it’s worth it.

And once a visibly disabled person becomes pregnant, they may hear a whole other bunch of uncomfortable questions. What did the women you interviewed say?

Women in wheelchairs got these super-invasive questions, like: How did you get pregnant? Do you have a man? Can you have sex? As disabled people, we are very used to other people feeling entitled to very private information. People on the street will ask: How did that happen? Why do you walk that way? Why do you look that way? But “can you have sex?” is such an incredibly bold thing to say to another person — except if you were about to have sex with them, I guess. As much as many women I spoke with were obviously, like, “Wow, this is inappropriate,” in another way, it forced people to say the quiet part out loud.

What’s the quiet part?

The thing that we, as disabled people, know [what] people believe about us and say about us — not to our faces. Suddenly, when there is clear evidence that this woman had sex, it forced people to say: I don’t think people in wheelchairs have that. I think that’s gross or I think that’s impossible. I’m disturbed that this person could do this thing with their body that a “normal” person does. So it almost forced the conversation.

All parents — and Jewish parents, to be sure — feel guilt about what they can and can’t do for their children. You write that there’s often an extra layer of guilt for disabled parents. Why?

I think our culture pushes mothers to feel guilty about things that are often out of our control. [For disabled mothers], because there are so many places where we’ve been kept out or disqualified from throughout our lives, we’re more trained to see our particular limitations as disqualifying — and also to see them as unique when, in fact, all parents have limitations.

There’s a layer of, God, I’m not able to do certain things we consider so basic to motherhood, even though I can do lots of other things that are basic to motherhood. And I feel both guilty that I can’t do what the mother downstairs from me can do, and a degree of shame in instances when I’ve been out in public and I’m facing these limitations. I’m thinking of the time when my son was old enough to walk on his own but didn’t want to. Someone else would have just scooped up their kid and walked the rest of the way. But because I’m very limited in what I can lift and carry, I had to sit there and negotiate with him. I felt eyes on me.

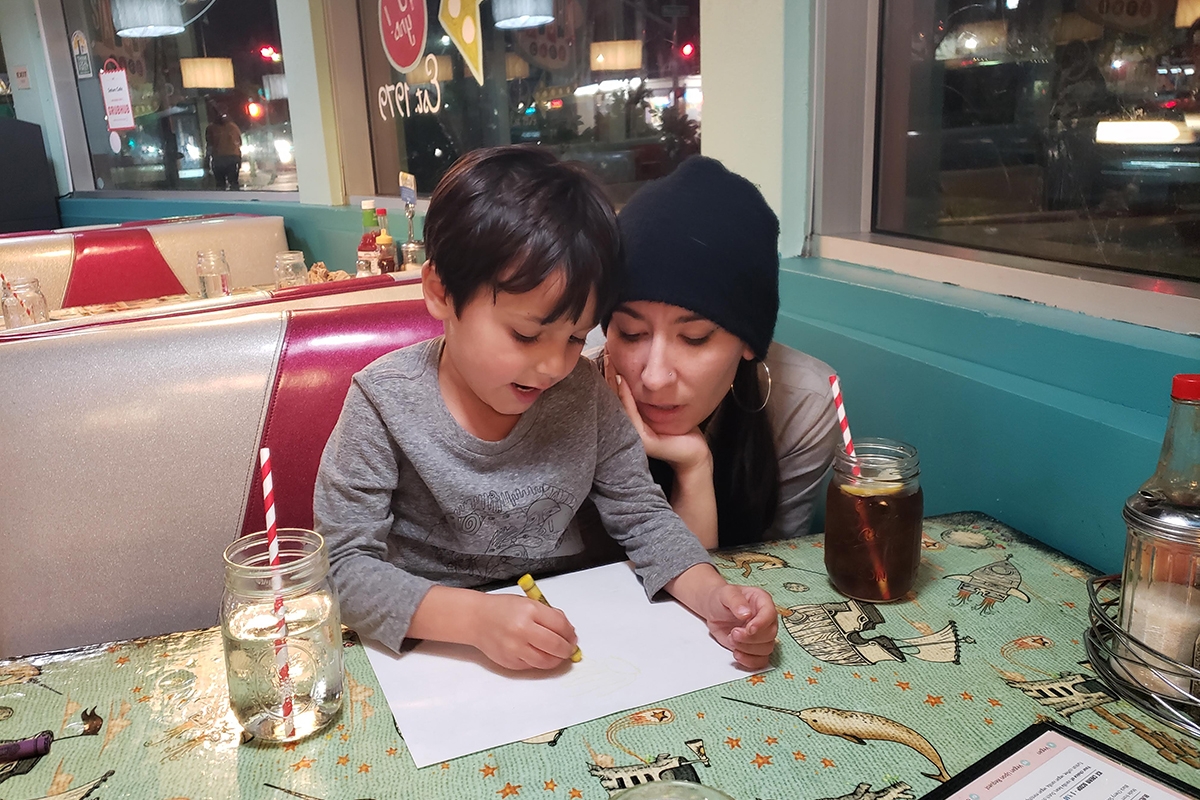

Sonja Sharp and her child

How can non-disabled parents be better allies to disabled parents?

I think a really good concrete step to take, if you are organizing a PTA meeting or even a birthday party, is just to think a little bit about: Do I want to put something on the invitation welcoming people to tell me about their access needs? Is there a way to look at the location ahead of time to make sure that someone would be able to enter and use the bathroom? Simply being aware that if you were going to make an accommodation for a disabled child, you should be thinking about making accommodations for disabled parents — because statistically, you’re more likely to encounter the latter — would be a huge paradigm shift.

And how can the Jewish community foster more of a sense of belonging among disabled adults, including parents?

There are many answers, but one that pops to mind is to consider the spiritual or ritual needs of disabled adults, as well as our physical needs. Not only is the mikveh accessible, or is there a way to ensure an autistic congregant is comfortable at kiddish after services, but if we have a community tashlich at the beach, is everyone who might want to participate able to do so, or even invited to do so? So much of our spiritual and communal life is informal — Shabbat lunches in homes and meetups in parks. Would someone with Crohn’s feel safer to join that activity if they knew for sure there was an open toilet nearby? Would someone with M.S. be more comfortable if we sat in the shade? People typically ask me if I can access something because my disability is visible. But lots of people could benefit from those kinds of questions, whether or not they have a disability we can see.