Growing up, Robin Rosenthal thought of Yiddish as a language of love.

“No one in my immediate family spoke fluent Yiddish, but Yiddish words were integrated into our everyday life,” the children’s book illustrator told Kveller over e-mail. “In our family we never really said ‘head’ or ‘hands;’ it was always ‘keppie,’ ‘keppeleh,’ and ‘henties.'” The Yiddish word for behind — tuchus, and it’s cute diminutives tush and tushie — were also in heavy rotation in the Rosenthal family, lovingly spilling out of the mouth of Rosenthal’s Nanny, her grandmother Edith Goldman, to whom her latest book, “Sweet Babe: A Jewish Grandmother Kvells,” is dedicated.

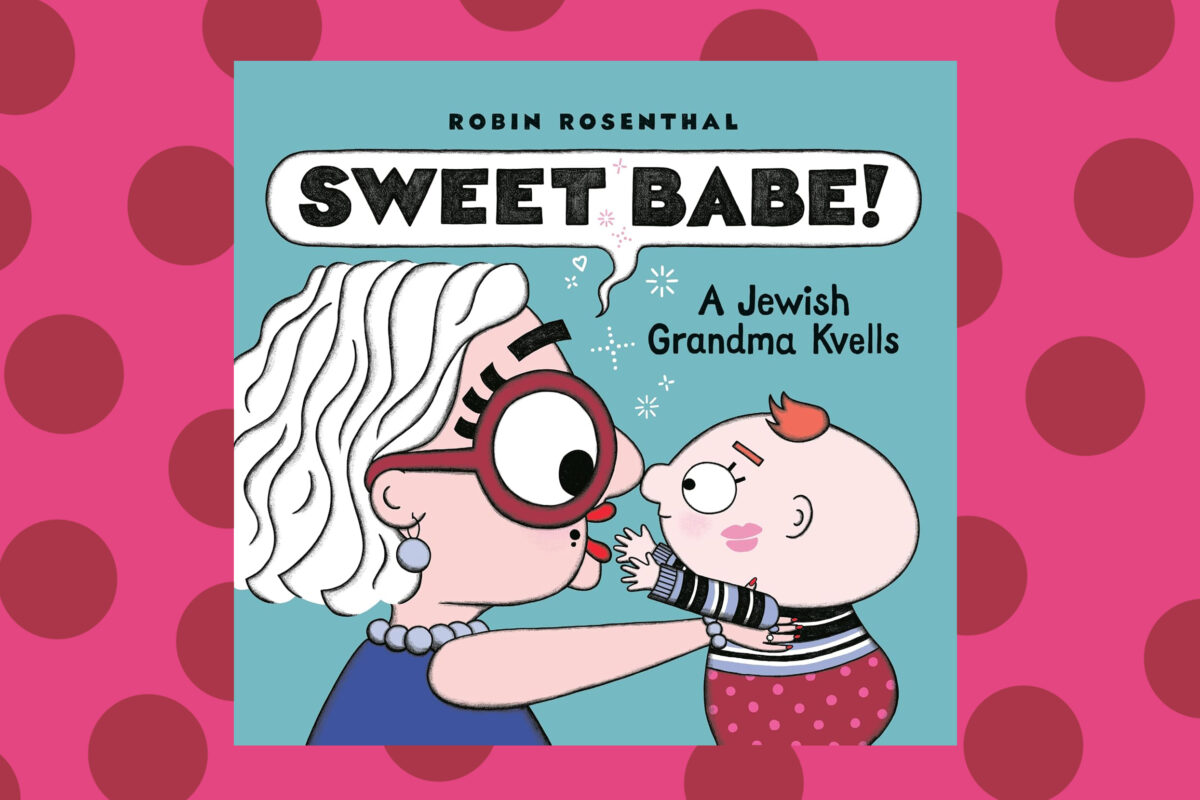

Through its colorful pages, Rosenthal is sharing that language of love with a whole new generation. In it, an effusive grandmother, wearing thick red glasses, dotes on her darling redheaded grandchild with Yiddish-peppered compliments. She admires the bubbeleh’s (sweetheart) punim (face) and keppie (head), “noshing” (snacking) on his delicious pulkies (chubby thighs), all while playing hide and seek with her sweet little babe. The illustrations are wonderfully expressive and adorable. Rosenthal even paid tribute to Jewish Russian constructivist and Dada-ist artists including El Lissitzky (who began his career illustrating Yiddish children’s books) and Henryk Berlewi, responsible for so much iconic Yiddish typography and design, through the book’s hand-drawn lettering.

The last pages of the book offer a delightful Yiddish glossary, in which Rosenthal maps out all the baby’s body parts, and gives us the Yiddish word to call his trusty pup along with other important Yiddish words featured in the book, including, perhaps most importantly, the word kvelling: “bursting with pride.”

Beyond its frequent Yiddishisms, the book embodies the Jewish spirit of kvelling through its big blocky text, a grandmother’s face, brimming with delight and through a very respectable number of exclamation marks — there are 23.

“My family loves their kvelling in a way that feels specifically Jewish, and it’s not just because of the use of some Yiddish words,” Rosenthal tells Kveller, “but also the hyperbole, the emphatic speaking, the passion.”

There is a bit of a shadow of sadness behind it all, as there often is in Jewish tradition: sweetest babies are a reminder of our survival as a people which fuels a particularly Jewish joy when faced with new life. “There is some pathos mixed in with the way Jews respond to new life. There is a sense of loss as a Jewish community and within individual families that makes the sweetness of new life feel sweeter and more poignant,” Rosenthal shares. “I had an older brother who died at age 2 from Tay-Sachs disease before I was born. This is one of the Ashkenazi Jewish genetic diseases that we screen for today but couldn’t back in the ’60s, and this has been something that has always permeated our reverence for life and health in our family.”

While Jewish moms and grandmothers in pop culture are typically overbearing, meddling and constantly worried, Rosenthal’s grandmother in the book is just loving, fearless and in love with her child. It’s an experience many Jewish readers will find familiar, and it’s one that the author and illustrator replicated from her own childhood.

“I grew up in a very demonstratively loving family, and we have an all-encompassing love, awe and fascination with our littlest family members,” she says, especially Nanny, whose voice Rosenthal says she channeled to write this book. “Nanny is directly quoted throughout this book several times and when I read it out loud, it is with her voice.”

The book, she affirms, “is a celebration of Jewish joy, and Nanny’s memory is a blessing.”