Juggling a house full of kids, a full-time job, volunteer work, and a social life. These are the unique struggles of 21st-century parents, right? Maybe not.

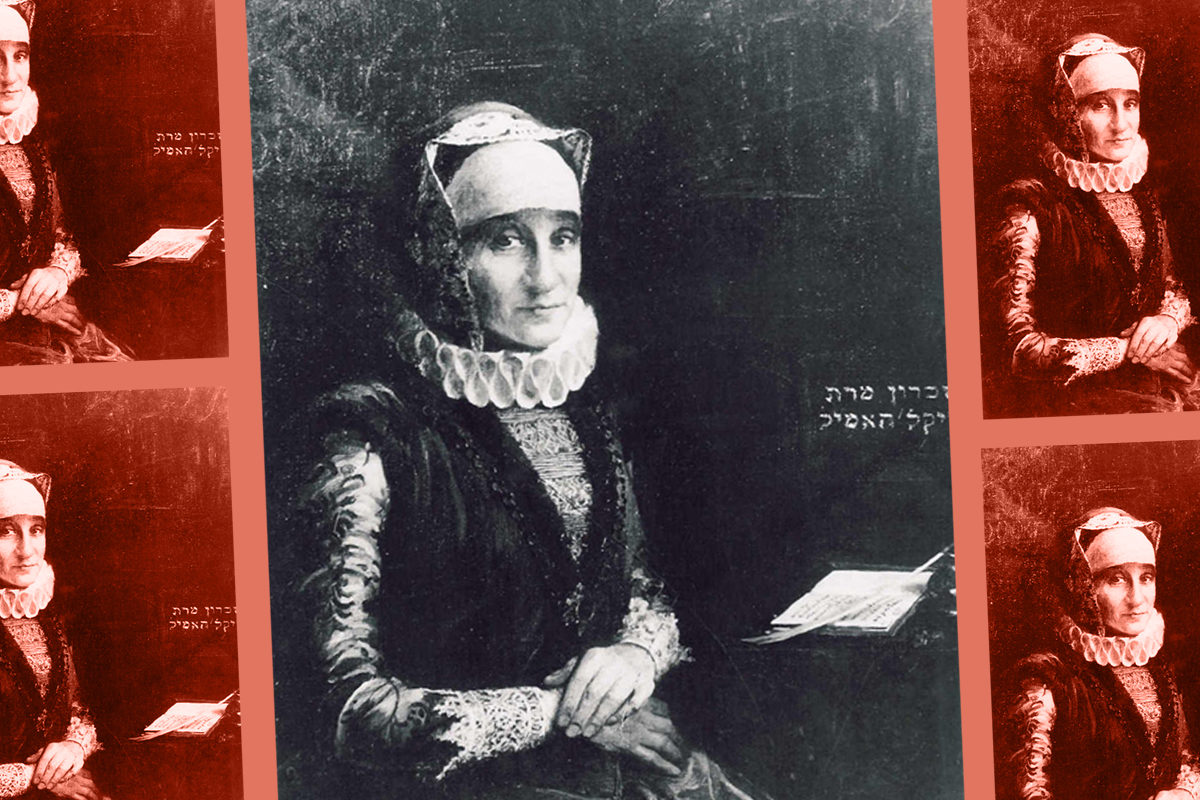

Glückel of Hameln — or, more accurately, Glikl bas Judah Leib, the Yiddish name she herself used — was “leaning in” more than three centuries before Sheryl Sandberg coined the phrase.

Way back in 1690 — not a typo! — this 44-year-old single mother of 14 kids ran a business and found time to write a memoir, all this in an era when most women couldn’t read.

She left us a record of Jewish history and a priceless snapshot of women’s lives — the only pre-modern Yiddish diary written by a woman, in fact. Incredibly, aside from the lack of technology and modern conveniences, her life doesn’t seem all that different from our own.

Glückel’s memoir, which survived thanks to a copy made by her son, Moses, was originally published in 1896 by David Kauffman. (He is the one who dubbed her “Glückel of Hameln,” in order to match German naming conventions.) In 1932, Marvin Lowenthal published the first English edition, and another translation by Beth-Zion Abrahams followed in 1962. Despite its age, Glückel’s timeless story demonstrates that today’s busy parents aren’t facing unprecedented challenges, and that there have always been multiple ways of being a mom. Even three centuries ago, women had complicated lives full of difficult decisions.

Of motherhood, Glückel writes: “I was tormented with worries as everyone is with a little house full of children, God be with them! And I thought myself more heavily burdened than anyone else in the world and that no one suffered from their children as much as I.” Update the language, and this sentiment would be perfectly at home in a contemporary motherhood memoir or blog. Parenting is tough, full of anxiety, and we often feel alone. And yet we can find comfort in Glückel’s words, knowing that this has pretty much always been the case.

By sharing her experiences, Glückel speaks to us about dilemmas we still grapple with: How do we juggle all that’s demanded of us? Should we feel guilty for working outside the home? How much should we do for our grown kids? And are we ever doing enough for our kids? Even if there are no concrete answers, it’s reassuring to know that we are far from the first generation to fret over these issues.

Glückel married young, as was common at the time, but she was no passive 17th-century stay-at-home mom. By age 25, she and her husband, Chayim, were running a successful business, buying and trading precious and semi-precious stones, mostly pearls. Chayim, she says, “took advice from no one else, and did nothing without our talking it over together.” It seems they had a more egalitarian marriage than we might assume (#RelationshipGoals).

Before Chayim died in 1689, he was asked for any final instructions. Rather than appoint a male guardian for the business or the children, as was common, he said, “My wife knows everything. She shall do as she has always done.”

Glückel was left with eight of their 12 living children at home to care for, two of them still toddlers. She was responsible for feeding all of them, keeping a roof over their heads, and planning their futures. Her husband died heavily in debt — yet somehow she managed to have it all paid off within a year. It’s a wonder that she ever found the time to write anything down.

And yet, somehow she did. (Through, she says, “many wakeful nights.” Perhaps this is the most relatable thing about her?) Glückel relays her anxieties about leaving her children while she travels for business: “after twelve weeks’ absence found my children and all the family, praise God, in excellent health.” Other stressors include managing the household, educating her children, arranging their marriages and planning weddings, fulfilling her obligations to the community, and fears about political events erupting around her.

Despite being a Renaissance Wonder Woman, she still worried about how others judged her as a woman and a mother. She details the struggle she had with one older son in particular: “I saw my son Loeb, a virtuous young man, pious and skilled in Talmud, going to pieces before my eyes.”

Today, Gluckel might be accused of being a “helicopter parent.” She’d been bailing Loeb out for some time, paying his debts to avoid embarrassment. Finally, she says to him, “Alas, I see nothing ahead of you. As for me, I have a big business, more indeed than I can manage. Come then, work for me.” Like so many of us, she was willing to do whatever she could to help her kids, even at great personal cost.

Gluckel’s account also assures us that, like us, harried moms in history made mistakes too, like the time everyone showed up for her daughter’s fancy wedding and she realizes the ketubah hadn’t even been written.

And amidst all of this chaos and daily grind, Glückel suffered multiple tragic losses in her family, as well as a few close calls. During an outbreak of the plague, her young daughter was sent away for fear that she’d contracted the deadly disease. Thankfully, she had not, but the ordeal was agonizing.

On top of all that, Glückel traveled frequently to conduct business; risking pirates, thieves, and lands where simply being Jewish was dangerous in itself.

It was many years before Glückel reluctantly remarried. Unfortunately, that marriage wasn’t as joyful as the first. In fact, her second husband ran her business into the ground and squandered her dowry. Her diary pauses for the entirety of that union, until he, too, passes away. Then she resumes writing in order to finish the account she started 15 years earlier. Though it took longer than intended, she did record her entire story.

It’s been 300 years since she put down her pen, and Glückel is still not forgotten. Perhaps because we can still see so much of ourselves in her.