This article is part of Back to School? a series on pandemic parenting and school reopenings, co-published by Kveller and the Jewish Telegraphic Agency.

A Jewish day school in Oakland, California, is committing to making changes after a local family said the school had declined to accept their gender-fluid child.

Meg Keene, an Oakland mother who runs a prominent wedding planning website, encouraged her thousands of Instagram followers to contact Oakland Hebrew Day School after she said the school told her family it would not admit her son due to his gender expression.

She said that after discussing the situation with the school several times, her family was informed that it would not be able to accommodate her 7-year-old son. The boy, whose name they asked to be withheld for privacy reasons, mostly wears traditional boys’ clothes but at times dresses up in sequined ball gowns and other feminine clothing.

Keene said she was inspired to call out Oakland Hebrew Day by name after hearing about another family who said their transgender child was also not welcomed by the Orthodox Jewish school. Ofra Daniel, an Israeli-born playwright, said she was told her daughter could attend only if she did not discuss being transgender.

“Never in a million years did I think the SCHOOL wouldn’t be up for doing their best,” Keene wrote in an Instagram post Sunday, two days after first informing her followers that her family had received the disappointing news.

“I know that by speaking out I might become a Difficult Jew that no Jewish day school will want,” she wrote. “But it’s worth the risk. Because this isn’t just about my kid. This about other kids being harmed. This is about changing culture. This is about doing better.”

Dozens of Keene’s followers reached out to Oakland Hebrew Day’s board, thrusting the school and the local Jewish community into debate at an already challenging moment, when the head of school is out on bereavement leave and the prospect of in-person learning is uncertain because of the pandemic.

Oakland Hebrew Day administrators say the school “had not completed the admissions process when the family went to Instagram” and indicated that they had not ruled out accommodating children who identify as gender-fluid. In a letter to families sent Wednesday, they also committed to evaluating the school’s policies around gender and offering staff training on gender and LGBTQ inclusion issues.

“While we do not understand the situation to have transpired as it was described in the social media post, we are taking the time to better understand the facts,” the head of school, Tania Schweig, and board president, Jo-Ellen Zeitlin, said in the letter. “We recognize that it is important that we take this moment to reaffirm our commitment to an inclusive educational environment.”

The story in Oakland underscores the complexity of gender issues in the Orthodox world, and sheds light on the complications that can arise when Jewish families and Jewish schools have overlapping but not identical values.

Some Jewish schools, including a now-defunct school in the Bay Area where a student came out as transgender during a bar mitzvah ceremony created for him by the school’s rabbi five years ago, have grappled already with gender and sexuality differences among their students.

But Oakland Hebrew Day is associated with Orthodox Judaism, which does not allow same-sex marriage and in which transgender and gender non-conforming people often face challenges in being accepted.

Still, if any Orthodox school might be open to gender-fluid or transgender students, it would be Oakland Hebrew Day. It’s located in one of the most progressive regions in the country. Some children keep kosher and observe other elements of Jewish law at home, but others do not. The student body includes children of same-sex and interfaith couples.

All of that attracted Keene and her husband, David Mishook, when they began looking for a new school for their children this summer.

Their son and daughter had been attending public school in Oakland but felt isolated, as there were few other Jewish kids in school. The school’s rocky transition to online learning had exacerbated the challenges, and rising anti-Semitism nationally had put the family on edge.

Oakland Hebrew Day, located just five minutes from their home, bills itself as “serving families from the diverse Bay Area Jewish community.” Keene and Mishook thought that would include their family — they most often attend Sha’ar Zahav, the historically gay synagogue in San Francisco — so the family reached out to find out whether there might still be space for their children.

At first, Keene and Mishook said, things felt promising: The school indicated that there might be spots open for this fall, and they had a warm conversation with staff members. But the mood changed, the couple said, at the end of their first Zoom call when they revealed that their 7-year-old son is gender-fluid.

The couple knew that their son’s gender fluidity might present a challenge for an Orthodox school, but they were optimistic. And at first, they said, the administrators seemed open to having their son on campus.

But after several weeks and another conversation, school officials reached out Friday with disappointing news: Mishook said he was told that the school could not accommodate their son due to his gender expression. Shortly afterward, Keene began sharing the family’s story.

Oakland Hebrew Day said the couple’s account is not accurate but did not dispute specific details.

“Our relative silence on the details of this matter should not be taken as defensiveness,” the school said in a statement Thursday. “OHDS has a long and proud record of working with families and students from every background and doing so with dignity, empathy, and respect. This family is at liberty to tell their story in a way that our institution is not. We respect confidentiality and regulations put into place to protect students and families. We will not disclose the content of our interactions with this family or any family.”

Previously, the board president, Zeitlin, said a final decision had not been made about whether to admit Keene and Mishook’s son.

“Gender fluidity was one of several issues the family raised during the admissions process,” Zeitlin said in a statement. “We were unable to fully explore this issue but are confident that we would have exhausted the possibilities for the child to enroll if the family and school agreed it would be a success.”

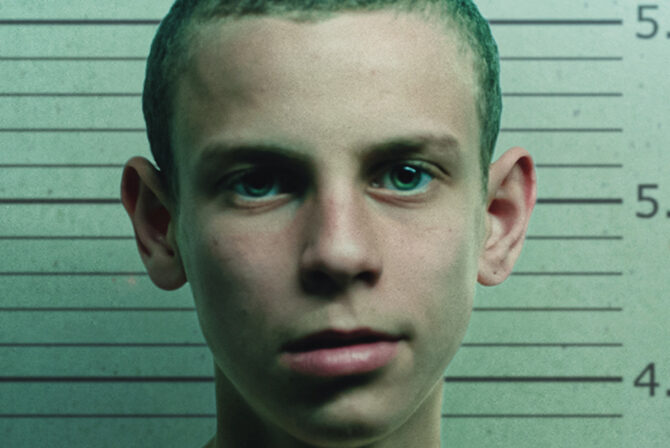

Oakland Hebrew Day School disputed Keene and Mishook’s version of the incident. (Google Street View)

That Oakland Hebrew Day might have struggled with whether to admit a child who identifies as gender-fluid is not surprising, said Rabbi Shmuly Yanklowitz, the founder of Torat Chayim, a rabbinic group for progressive Orthodox rabbis.

“Essentially the educational framework in Orthodox institutions is very gender binary, and the tools and language have not yet been developed adequately to handle a non-binary approach to gender,” Yanklowitz said. “And so I think families and schools in the community don’t yet feel equipped to juggle that complexity while maintaining an authentic commitment to Torah, mitzvot and Orthodox norms.”

But Yanklowitz, who is also the founder and president of the Orthodox social justice group Uri L’Tzedek, said he is seeing an increased willingness in the liberal Orthodox world to challenge those long-held norms.

“There are few issues where I have witnessed such a rapid evolution and thinking as in issues of gender fluidity and thus I remain very hopeful that we will witness progress in our gender-inclusion policies that still maintains our commitment to authentic traditional Judaism,” he said.

Religious private schools such as Oakland Hebrew Day are given wide berth to discriminate in admissions and enrollment as long as the choices are consistent with their religious tenets.

Mishook, who works as a lawyer, said the two Oakland Hebrew Day administrators who relayed the admissions decision to him by Zoom suggested that the school was not opposed to accommodating gender-fluid children in the future. (Keene wasn’t on the third Zoom call.)

“Ultimately they said that they felt like while they could support him this year, they weren’t sure about going forward,” Mishook said. “They said straight out, ‘We feel like we haven’t done the work to support him. That they wanted to do the work and they were going to do the work and effectively. Maybe you can come join us in the future once we feel able to support a gender-fluid child.’ That was sort of their message.”

But according to Daniel, the Israeli-born playwright, the school has had at least one chance already to become more inclusive around issues of gender.

Daniel, who lives in adjacent Berkeley, said she was told last year that her daughter could enroll in sixth grade only if she did not speak about being transgender at school. (Her older son already attended Oakland Hebrew Day.)

“’If she came to us as a girl, we’d take her,” Daniel recalled the school saying. “But we don’t want to expose other kids to transgender.”

Oakland Hebrew Day disputed Daniel’s story, too.

“Our engagement with the family was far more nuanced than presented,” Zeitlin said about the admissions conversation about Daniel’s daughter.

Zeitlin emphasized that the school was welcoming to a wide range of families — including same-sex couples.

“We currently have — and have in the past had — gay and interfaith families in our community,” Zeitlin said. “We welcome families who are looking to provide their children with meaningful Jewish experiences and education.”

As of this week, Schweig and Zeitlin wrote in their letter to families, the school has embarked on a process to create policies on gender issues and educate staff about LGBTQ issues.

“This is a moment for introspection and action,” they wrote. “Our exchanges with [Keene’s] family showed us that we at OHDS still have work to do. … We welcome families, religious leaders, and community-based organizations to partner with us as we begin this important process.”

Keene annotated the school’s letter to families on Instagram.

“This is a pretty good letter. It would be a very good letter if they had backed it up by reaching out to us with empathy to try to change or fix things,” she wrote. “The fact that they haven’t means that right now it’s words without action.”

For her family and for Daniel’s, any changes at Oakland Hebrew Day will come too late. Daniel’s daughter attends a local public school, and Keene and Mishook’s son just started his first week of second grade at his public school, which is operating online only for the foreseeable future. He and his sister are on a waitlist for a different Jewish day school.

“I’m well aware that by going public we may now be a family no day school wants,” Keene wrote Wednesday after posting her annotations of Oakland Hebrew Day’s letter on Instagram. “I know that was the risk I was taking. I decided to do it anyway.”

Her son isn’t aware of what happened with Oakland Hebrew Day.

“I don’t want him to know that he was rejected from a school,” she said. “Life is hard enough for him. He’s also been bullied and hit and stuff like that for gender expression and his current school has not been a safe environment for him consistently. He and his sister are both interested in going to Jewish school, and I don’t want him to know that a Jewish school says he can’t go because of that.”

This piece originally appeared on JTA. Maya Mirsky, a reporter for J. The Jewish News of Northern California, contributed reporting.

Header Image by Kenzie Kate via JTA.