Anita Diamant is something of a literary Renaissance woman. Known the world over for her bestselling novels The Red Tent and The Boston Girl — among others — she is also an award-winning journalist and the author of popular Jewish guidebooks like “The Jewish Wedding Now” and “The New Jewish Baby Book.”

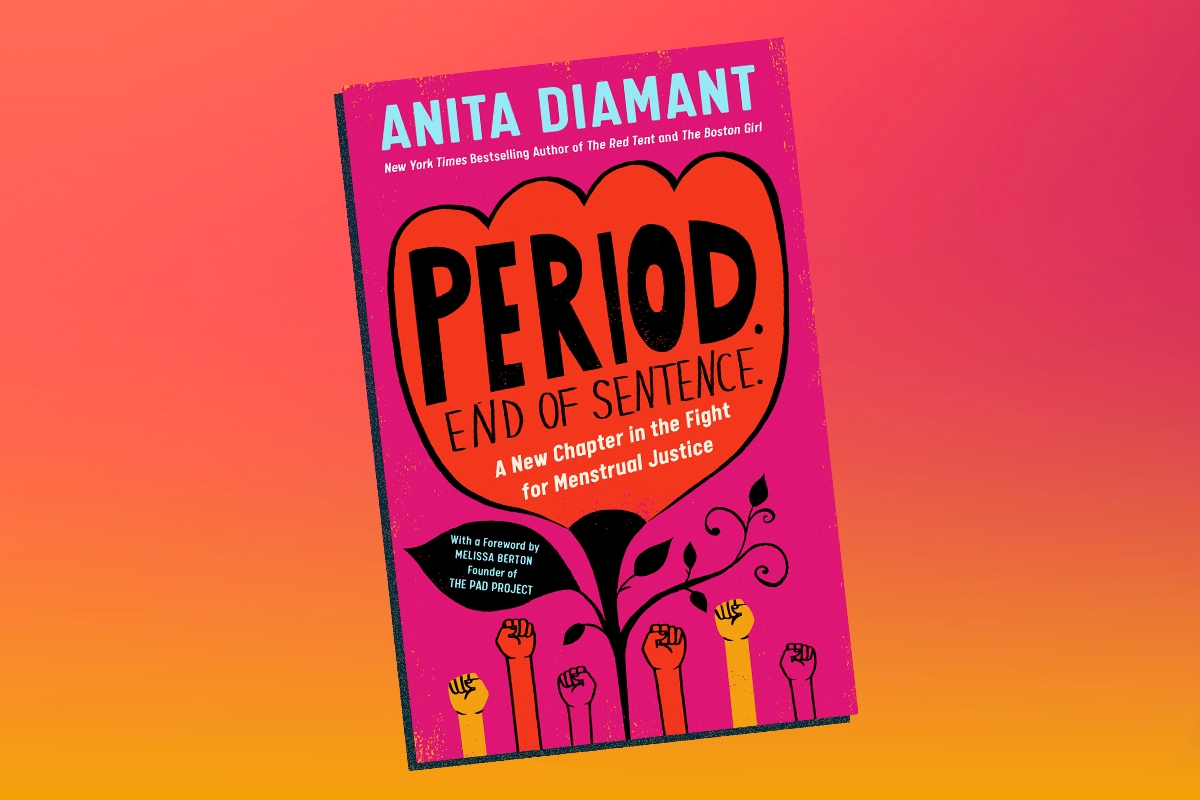

Her latest work, Period. End of Sentence., published in May, is a stirring collection of essays, interviews and testimonials that examine the ways menstrual injustice affects us all. Echoing the theme of female empowerment that makes her novels so compelling, Diamant challenges the belief that menstruation must be a shamefully kept secret. “Menstruation is not the curse,” she writes, “shame is the curse.”

Anita Diamant. Headshot via Gretje Fergeson.

I talked to Diamant about menstrual injustice, celebrating first periods, and how destigmatizing menstruation is a Jewish issue in more ways than one.

This interview has been condensed and lightly edited.

The Red Tent is such a symbol of female empowerment. It seems like a natural progression that you would come to write Period. End of Sentence. What was the inspiration behind this book?

I am not sure it’s a “natural progression.” I wrote the book because the creators of the Oscar-winning documentary “Period. End of Sentence.” asked if I was interested in writing a book inspired by the film. Of course, they asked me because I wrote a best-selling novel that centered on women’s lives, where they considered menstruation a positive, normal part of life — a source of life.

When we talk about menstrual injustice, what are some issues that come to mind?

There are so many issues and situations. There are parts of the world where menstruation is seen as pollution and you have to wait it out in separate, often dangerous, conditions. There are places in the U.S. where menstrual injustice is blatant and terrifying, like the adolescent girl who was being held at the southern border, who bled through her clothes and had to wait an unconscionable amount of time to take care of her basic needs.

For menstruators who are incarcerated, guards have exacted money and sex in exchange for tampons and pads. For poor families who must choose between food and rent, period products are a luxury. Imagine trying to concentrate in middle school when you’re worrying about staining your pants. A big part of the problem is internalized shame — expressed in invisibility and silence — which seems to confirm that menstruation is a curse and that you are cursed.

Was the “red tent” of your novel purely imaginary or are there any ancient Jewish traditions that we can look to as we try to move toward a more period-positive culture?

The red tent of my novel was my creation. I knew there were menstrual huts and tents in pre-modern cultures, but that was about all I knew at the time. Most of what I found back then suggested that menstrual sequestration was a kind of punishment. But I decided to characterize it as a place of rest, community and sisterhood.

Mayyim Hayyim, the mikveh [Jewish ritual bath] I helped found 17 years ago, can be seen as an example of using the past as a source of positive period thinking.

Reclaiming the mikveh experience sounds like a step in the right direction. Can you talk more about menstruation, mikveh and Mayyim Hayyim?

Mikveh — the ritual bath — is an integral part of niddah observance, which comprises the laws concerning married couples and menstruation. These laws are about regulating sex, which, according to Jewish law, was to occur only between married, heterosexual couples. The whole system is built around the menstrual cycle and stands on the idea that bleeding women are tamei [ritually unready].

But that status is treated as if it [menstruation] was a kind of infection or curse so potent that even the touch of her hand would make the men around her tamei as well. To become tahor, or pure, women follow a male-created and regulated system of counting days and ritual cleansing in a mikveh. After that, the menstruating woman is no longer a threat to the ritual status of her husband.

Mayyim Hayyim is the community mikveh located in the Boston area that has pioneered the idea of “open mikveh,” providing immersions for those who are becoming Jewish and Jews of all descriptions, genders, and denominations who come for a wide variety of reasons — such as life transitions, endings, and beginnings. Immersions related to the monthly cycle comprise the largest number of immersions annually.

What makes these monthly immersions different?

What is radically different and empowering about monthly immersion at Mayyim Hayyim is that each person has control over the timing, liturgy and practice. For example, everyone chooses whether or not to have a witness or use the traditional blessings. Everyone interprets and performs the ritual in ways that are personally meaningful, breathing life into something that seemed rote to some and completely irrelevant to others.

The truly radical change here is that all menstruators have the agency and power to shape the mikveh experience in harmony with their own beliefs and practices, which at Mayyim Hayyim range from traditional/Orthodox to Reform to “just Jewish,” and everything in between.

In Period. End of Sentence., you talk about ways we officially and unofficially mark menstruation — everything from period parties to bat mitzvahs to “the slap.” As a mom, how did you talk to your daughter about her period, and did you mark it in any special way?

Neither my daughter nor I can remember anything about her first period. I knew there was a good health curriculum in her middle school, taught by a favorite teacher, and I never used euphemisms; she knew what was what. Today, I see that as a missed opportunity to acknowledge it.

Is a belated period party in order?

I’m not sure a party would have been the thing. Lots of mothers are keen to host a group of their friends to give blessings — you can just hear the eye rolls. I might have offered Emilia (my daughter) a choice: A day off from school to go out to lunch together? Her favorite dinner and a pedicure? Something we would both remember with a smile.

Doing research for the book, I found examples in non-Ashkenazi culture I wish I’d known about. For example, a friend from a Sephardic family told me that when she got her first period, her grandmother invited her to afternoon coffee and served all her favorite treats.

Other than reframing our own religion’s perspective on menstruation, is the broader fight against menstrual injustice a Jewish issue?

Injustice — in all its forms — is a Jewish issue. Many of us connect to our Jewishness through the work of repairing the world. American Jewish women in particular, who have long been deeply involved in the fight for gender equity, are now part of efforts to destigmatize this essential function of the human body.

Header image via Simon & Schuster