One morning last November, when I went for my 37-week pregnancy checkup, my doctor informed me that I was walking myself straight over to Labor & Delivery for an induction. While I waited to be admitted, my husband ran home to walk the dog and check off items on my birthing “to do” list, which including packing my hospital suitcase.

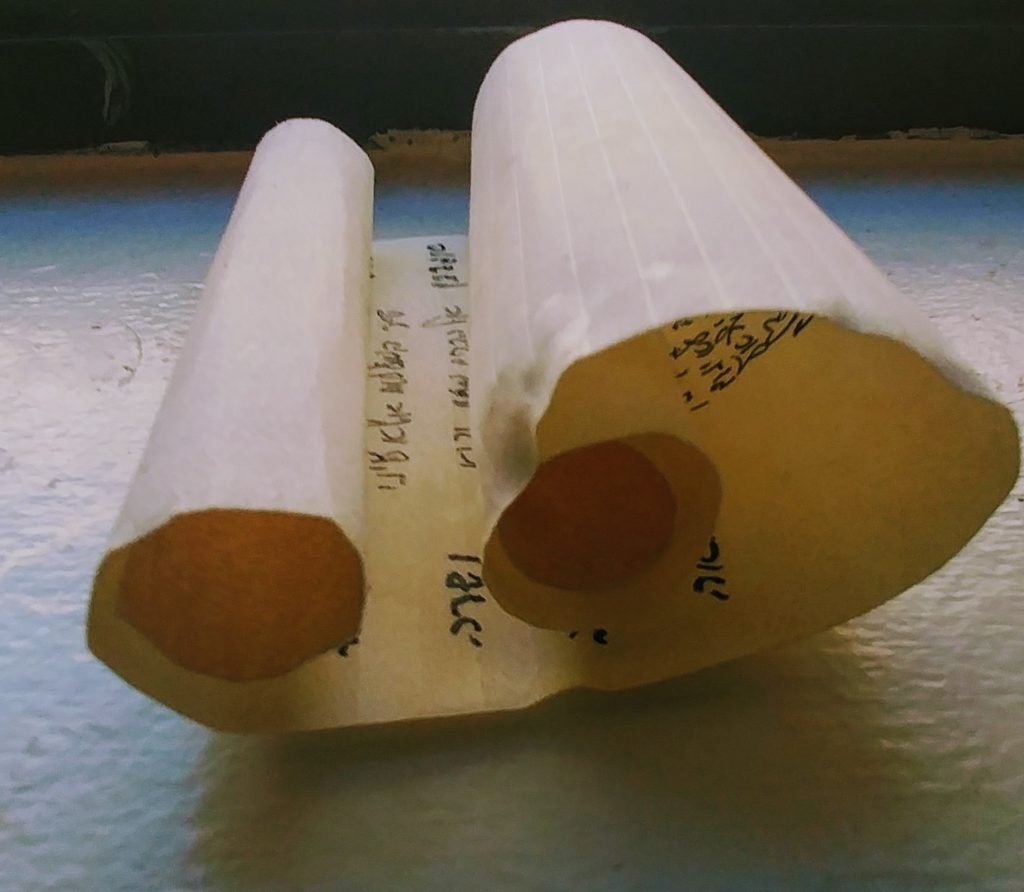

As he frantically completed these errands, he also found time to prepare something else for me: A Hebrew amulet with a protective prayer on it. Perhaps this wasn’t on your packing list, but my husband, a lawyer by day, also trained as a sofer, or Jewish ritual scribe. In his spare time, he is writing a Torah. So, he just happened to have parchment, ink, and quills on hand in our small Manhattan apartment.

Although the word “amulet” makes me think of dragons and “Game of Thrones,” the word — both in English, and in Hebrew (kamea) — really just means a small ornament used to give protection or ward off danger. In fact, many people have amulets without really thinking about it – a chai necklace, with the Hebrew letters for the number 18, which represents “life,” is a kind of amulet; a mezuzah, which Jews are commanded to place on their doorposts, is a kind of guardian for a home’s entrance.

Jewish amulets tend to be, unsurprisingly, a page of text, occasionally with a mystical diagram thrown in. In Eastern Europe, the amulet for childbirth was called a kimpetbrivl, from the Yiddish words kind (child), bet (bed), and briv (letter). These amulets were hung over the crib or over the mother’s bed, to protect the woman and child from evil.

Mothers were especially afraid of the appearance of Lilith, the Biblical Adam’s first wife, who fled Eden and became a demon. According to a 9th-century Jewish text, The Alphabet of Ben Sira — and as dramatized for generations in Jewish folk tradition — Lilith claims her purpose is to kill newborn Jewish children. Fortunately, she becomes powerless if confronted with an amulet bearing the names of the angels Senoy, Sansenoi, and Semangalof.

Jewish folk traditions like the kimpetbrivl were once widespread across the Jewish diaspora. But few examples remain today; most were written on scraps of paper or parchment, which were reused or discarded, or they did not withstand the elements over time. Many of these customs, and the material culture associated with them, simply didn’t survive the Holocaust, which caused a deep rupture of Jewish practices and teachings passed on by mouth.

Preparing for childbirth is powerful enough to shake anyone’s belief systems — and awed and terrified as we were about bringing a new person into the world, we figured we could use any extra bit of help. My husband and I don’t follow kabbalah or any other mystical or spiritual practice — I don’t even do yoga. But we decided that writing an amulet for me and our baby was the kind of superstition we would take seriously. After all, why tempt fate? It’s the same reason that we didn’t hold a baby shower, or even put together basic baby items like the car seat and bassinet, until our daughter’s arrival was truly imminent. We didn’t want to alert the evil eye, keyn ayin hore.

Like most traditional birth amulets, my kimpetbrivl included the text of Psalm 121, a prayer often recited to support healing. Next came an odd assortment of phrases meant to invoke protection and ward off danger. This includes a list of all the names of all the matriarchs and patriarchs, written as couplets, such as “Adam and Eve… Abraham and Sarah,” and “Isaac and Rebecca… Jacob and Leah.” On paper, the invocation of these Biblical figures feels powerful, a call out to the ancestors to protect their children’s children.

Most traditional Jewish childbirth amulets also include a quotation from Exodus 22:17, “A witch shall not be suffered to live.” The text is referring to Lilith, but refuses to name her, since that would give her power. As a feminist, I’m sensitive on the subject of Lilith, who, according to traditional texts, refused to accept subordination to Adam, because, as she argues, they were both made from the same earth. I asked my husband not to include this Biblical text on our kimpetbrivl (although we did include the names of the angels that have the power to defeat Lilith, Senoy, Sansenoi, and Semangalof). I’m sure the ghosts of a thousand Jewish women were horrified at this careless and possibly dangerous abandonment of tradition, but I decided to risk it.

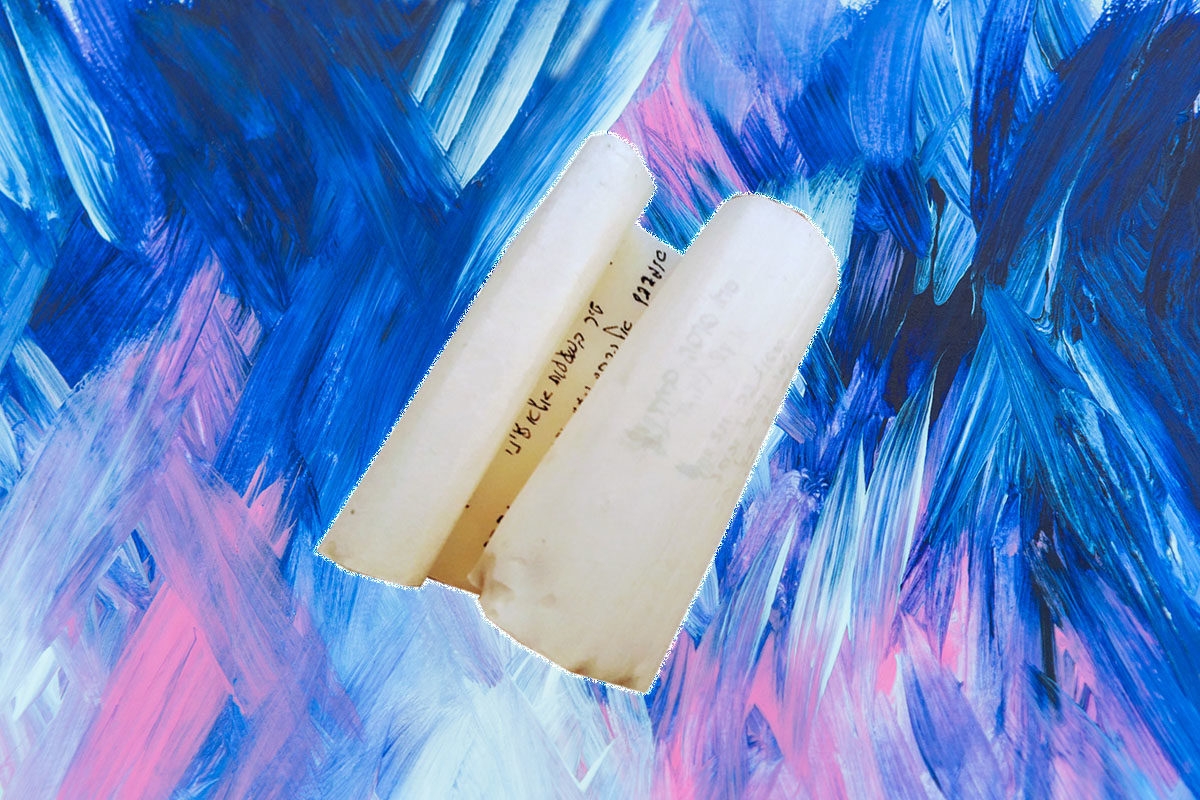

When I checked in at Labor and Delivery, I was assigned a bright, beautiful room overlooking the Hudson River. It felt like an auspicious beginning for our daughter. When my husband met me there, he handed me a wavy, slightly smudged scrap of parchment, the ink still fresh. We placed our amulet on the folding table of the hospital bed, next to the plastic cups and my chapstick. It sat there beside me for the next two days, attracting an inquisitive glance or two from various nurses and doctors as they went about their business. One of the nurses finally asked what it was, and we enthusiastically explained the concept to her, wondering if she thought, despite our rather plain, secular, appearance, that we were part of a cult. But when she heard our explanation of the amulet, she laughed encouragingly, and said, “There’s no doubt that the Labor and Delivery department sees its fair share of magical thinking around here, on top of all the medical science. After all, it certainly can’t hurt!”

Whether the amulet helped or not, I can’t say. But my experience of childbirth, while chock full of medical interventions, was overwhelmingly positive. I felt safe and protected during the entire process. This was in large part due to the excellent medical care I received, and also due to the fact that I knew we had good health insurance. But it wouldn’t have felt the same without that velvety piece of parchment curled up next to me, reassuring me with its promise of connection to generations of childbearing Jewish women. When my daughter was born on a brilliant Shabbat morning, nailing her Apgar scores and immediately charming her parents, we were certainly glad to have used every bit of both science and magic to bring her into the world.