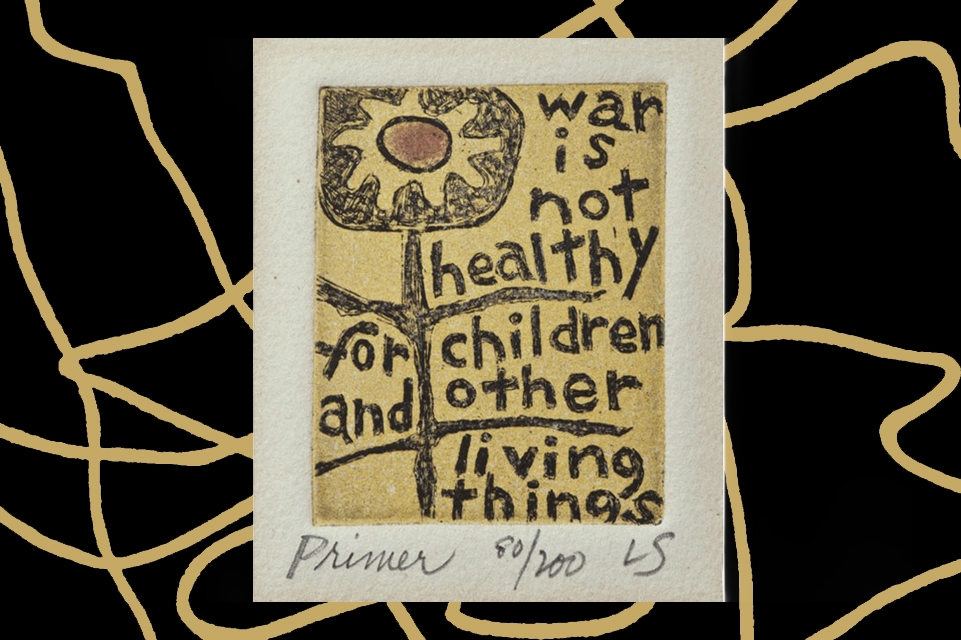

Two by two inches — that was the space allotted to artist Lorraine Schneider when making work for a miniature art show at New York’s Pratt Institute in 1965. In that small space, the artist, printmaker and peace and civil rights activist found a message that filled whole worlds.

That artwork, titled “Primer,” features the sentence “war is not healthy for children and other living things” in childlike script, juxtaposed with a black and white sunflower. It was made in response to the Vietnam War, but like other great works of art, has found a life well beyond that moment in history, popping up more recently during the war in Ukraine, a country Schneider was personally tied to, and where the sunflower is the national flower. And now it’s being used again, in art responding to the October 7 Hamas attack and the war in Gaza, which has taken the lives of thousands of children.

Schneider’s youngest daughter, Elisa Kleven, now a mother of grown kids herself, remembers her mother taking inspiration from the earnest letters she wrote as a child while learning penmanship. Kleven told Kveller last November that her mother felt like she had to make her “own personal picket sign.”

“I felt like it had to say something important or true, or it’ll just be an exercise in painting — you know, 40,000 angels on the head of a pin,” Kleven recalls her mother saying. “She just wanted to make something that nobody could argue with.”

Schneider didn’t get to see the long shelf life that her art would take on. She died at age 47, when Kleven, the youngest of Schneider’s four children, was just 14. “She raised children, and then she had a very brief and amazing career. And then she died.”

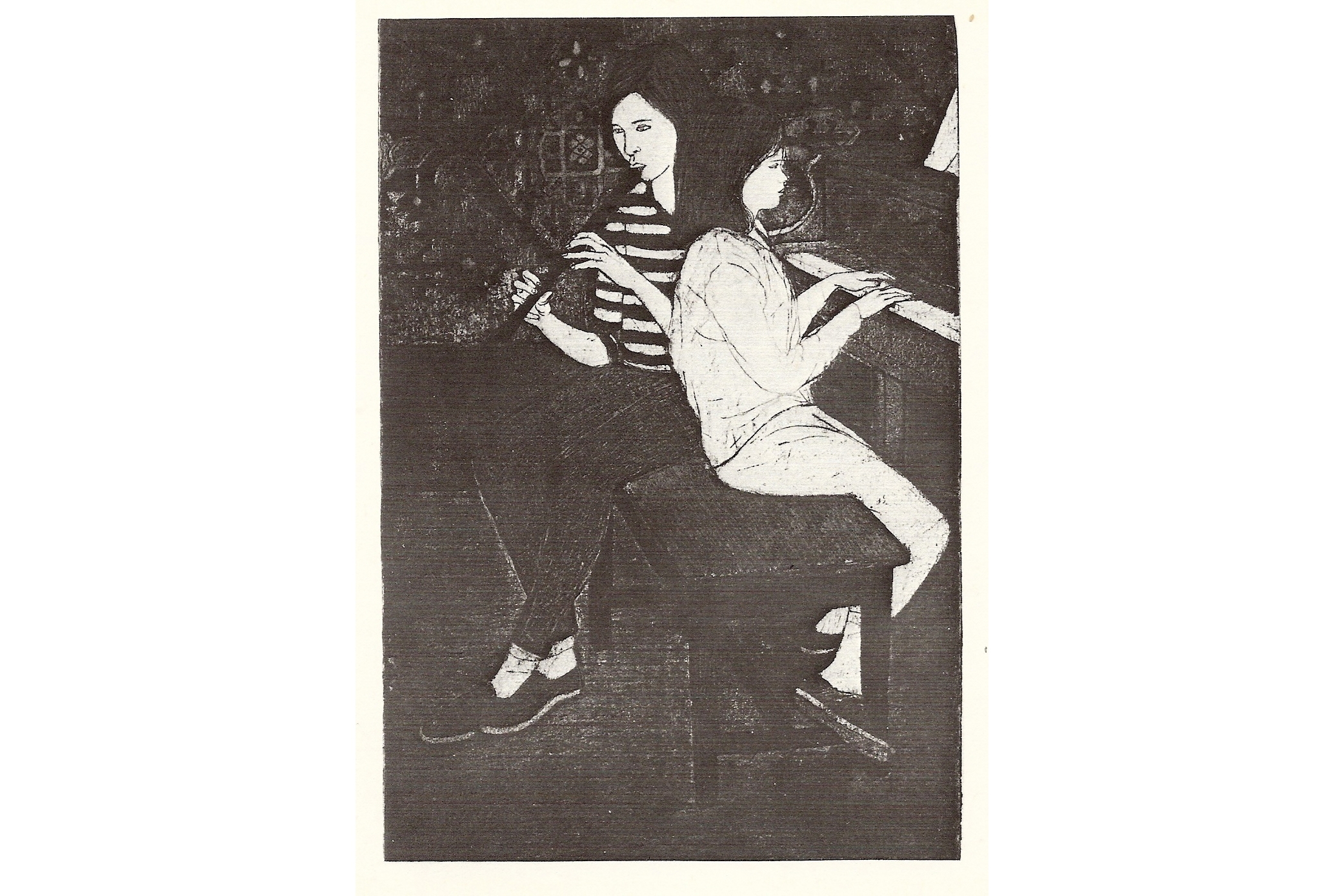

“Tapestry,” an etching by Lorraine Schneider of Elisa and her older sister.

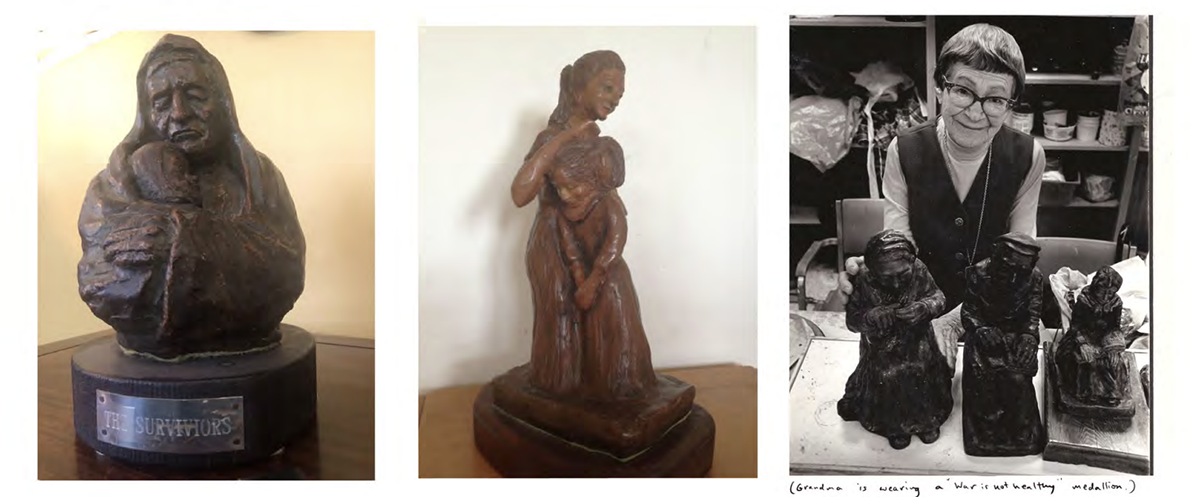

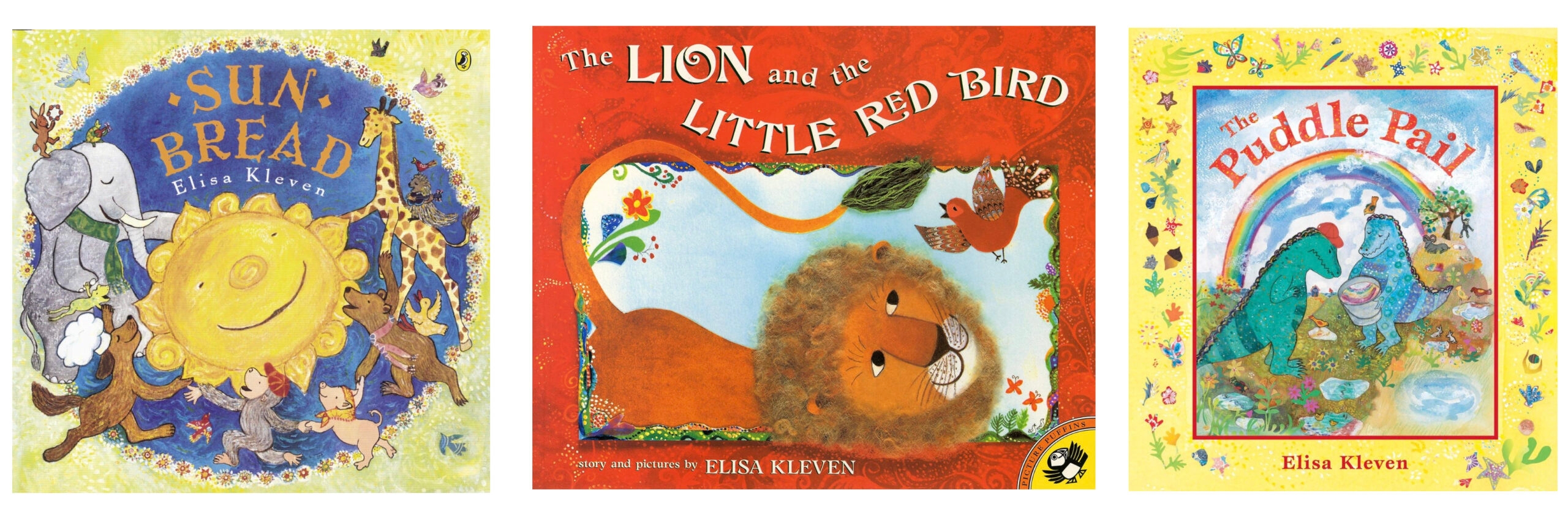

Kleven, like her mother, is an artist, a children’s book writer and illustrator who has written books like “Sun Bread” and “The Puddle Pail,” which are popular around the world. She is the third in a line of creative, incredible, Jewish women. Schneider’s mother, Eva Art, was a self-taught sculptor. Her art, like Schneider’s, was informed by war.

Eva escaped Ukraine for the States as a child because of the pogroms taking place in her hometown. A relative took her and her sister in, giving them a job at his Boston tailor shop. Eva and her sister tried to send money to get the rest of their family into America. But Hitler soon came to power, World War II broke out, and she lost contact with them.

Through the Red Cross, she tried to find out what fate befell her family, “but everybody was gone, the whole shtetl was gone,” says Kleven, sharing they were killed in mass graves before the killings in concentration camps began.

Art dealt with her grief through art. She used clay, the earthy material that reminded her of the shtetl, and made figurines of the dead: A boy and his dog. An elderly woman knitting. A rabbi reading the Torah. A woman sweeping the street. A little girl taking a sweet nap, her head cradled on her lap. A mother embracing a young baby.

Eva Art and her sculptures, courtesy of Elisa Kleven

Schneider grew up in the shadow of that unimaginable loss and her mother’s ability to channel it into her work. Before the Vietnam War, she worked with WWII veterans as an occupational therapist. She was active in the Civil Rights movement, and much of her art was about racial justice, protesting the treatment of Black Americans.

“I think she just always had a very strong sense of justice, and was a compassionate and non-violent person, so when Vietnam rolled around, you know, it just kind of came out in that way,” Kleven says. “I think it was just all part of that, her basic worldview.”

Her basic worldview was also informed by motherhood. She donated the rights to “Primer” to the organization Another Mother for Peace, whose motto was “no mother is an enemy to another mother.”

What is it about mothers that always puts them in the forefront of waging peace, I ask Kleven, thinking about slain activist Vivian Silver and the organizations Women Wage Peace.

“A good mother is an empath, because you feel what your child is feeling and want them to be healthy and happy. You’re sad when they’re sad — it’s pretty basic,” Kleven muses. “And then if you could extend it beyond your own children, I think that’s how peace is made.”

“Maybe I’m being too optimistic,” she adds. “But I think that if we could just harness that instead of hatred and violence… it would help the world a lot.”

While no one can really know how Schneider would react to the war in Gaza today, Kleven wagers a guess.

“I think she would be repulsed. I think she would be enraged by the pogrom that took place on October 7, but also, by the mass retaliation. The indiscriminate bombing of Gaza would also very much upset her. That’s how she was. She just saw the children and other living things who are the victims of war, even the animals and the nature, the environment.”

When I spoke to Kleven in early November, she was feeling raw in more ways than one. While trying to avoid hitting a squirrel on her street (she, like her mother, cares so much for living things) she got in a car accident. She was fine, luckily, but it’s strange how these accidents seem to happen when the world feels like it’s turned on its axis. Kleven was distraught that her mother’s words still needed to be repeated, that children are still dying. She listened patiently as I told her about my own feelings about the war. We marveled at the magic of raising children. And she talked about her own art, too.

Elisa Kleven’s children’s books.

Kleven’s children’s books are informed by the art of the women who came before her.

“I just wanted pretty things,” she tells me. If her mother’s and grandmother’s art was about war and suffering, and the world around her in 1960s California was filled with tumult, then “art was my oasis in the world. I wasn’t trying to protest anything. I just created my own peaceful world.”

Her art as an adult is an extension of that. “I like sparking imagination,” she tells me, and making children feel like they can make art like hers, too.

“My art is kind of childlike. Some art is dazzling, but it looks so out of a child’s grasp. So I use a lot of handmade, accessible scraps of things they can find around the house, or little bits of wrapping paper or newspaper or wool or scraps of cloth, you know, just little bits of things woven together. I think I’ve always really longed for peace and I try to make images that reflect that, or friendship. I don’t want a saccharine, sweet world, but I want one that’s full of hopefulness — peace and a creative resolution to problems usually are in my stories.”

“I just want all children to be able to make art. I always think of all the artists and visionaries who are lost in wars,” she says, her voice heavy with emotion. “How many amazing minds perish… I don’t know what’s wrong with humanity. Think of what a beautiful world we can have — funnel that into enriching rather than destroying life.”

Kleven draws her grandmother remembering Ukraine.

I reached out to Kleven more recently to see how she is recovering, and to ask if there’s anything she wanted to add as the war continues to unfold since we last spoke.

“I still feel overwhelmed by the violence and heartbreak in Israel, Gaza, and the region,” she writes back. “It’s almost too painful for me to contemplate. I give money raised from the Another Mother for Peace merchandise to causes which try to alleviate the suffering (Save the Children, World Central Kitchen), and that makes me feel a tiny bit less helpless.”

In her art, Kleven dreams of a better world, a world in which the women and children of her grandmother’s sculptures never perish in mass graves, a world in which we all know how bad war is, for all living things. In her world, children find solutions, animals make peace and the sun shines brightly above us all like her mother’s sunflower.

It is a world worthy of all our dreams. A world in which her mother’s words are always heeded. A world we need, so desperately.