In 2011, Els Kushner got a call that changed her life forever and — while this might sound like hyperbole — changed the course of Jewish kids’ literature forever.

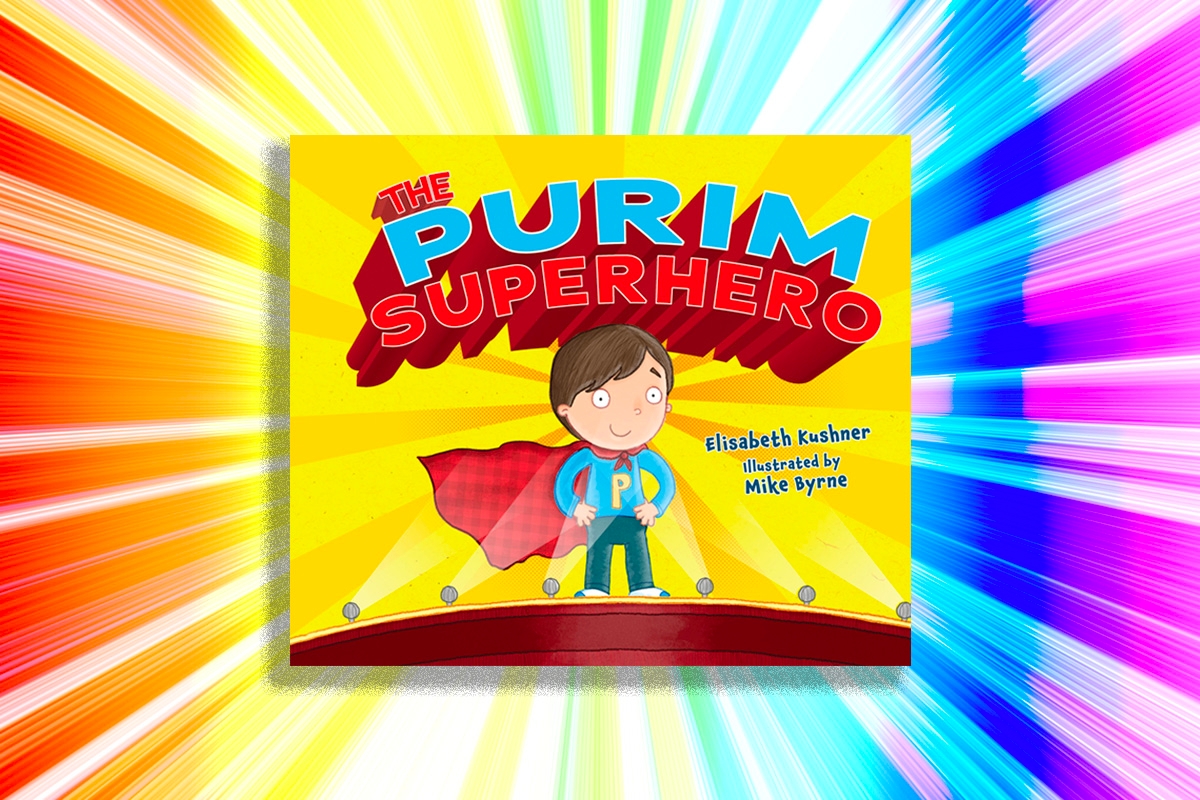

The call was from Keshet, a Jewish LGBTQ organization, telling Kushner that out of over 50 manuscripts, hers, “The Purim Superhero,” about a kid named Nate with two fathers and a costume dilemma, had won their LGBT Jewish children’s book contest.

“I just remember it was one of those moments where everything stops and crystallizes,” Kushner told Kveller about that moment. “And then I had to take my kid to the orthodontist.”

“The Purim Superhero” had been gestating in Kushner’s mind for a while before that — she had often lamented that Purim, a kid-friendly holiday, didn’t have more read-aloud books for young children to share with the kids at the Jewish day school she worked at. But in patching that hole in representation, she filled an even bigger one: “The Purim Superhero,” published by Kar-Ben on January 1, 2013, went on to become the first specifically Jewish LGBTQ+ children’s book.

It was Keshet that first saw that hole in representation, and wanted to fill it. Idit Klein, the CEO of Keshet, remembers why the organization wanted to host the contest. “We were not interested in the didactic book about being gay,” she told Kveller.

Kushner herself was the mother of an 11-year-old daughter at the time, and “The Purim Superhero” was the kind of book that she wanted for her daughter.

“The real model for picture books about kids and queer families 10 years ago,” she explains, was often a variation of “the same plot, which is, a kid has two moms or two dads and their family is happy. The kid encounters someone in the outside world, who doesn’t think their family is OK — might be a teacher, might be a peer, might be somebody in the neighborhood. And then someone else affirms that their family is OK, that there are lots of different ways to be a family, a lot of different ways to love.”

That wasn’t Kushner’s daughter’s experience. The Jewish spaces she had grown up in, in Seattle and Vancouver, were open and accepting. A family that looked like hers, with two moms, may have been rare, but “as far as she could tell, [my daughter’s] family was OK,” Klein said.

“I wanted to write a picture book about a queer family that would function as both a window and a mirror,” Kushner explained, using terms that today are prevalent in the children’s books industry. “[A book] that would reflect the experience of queer families that I knew and that I was part of, which was mostly acceptance, if not celebration.”

And most importantly, Kushner “wanted to write a queer queer picture book, where the queerness was not the problem.”

Jewish authors have long made queer book history. Jewish Author Leslea Newman wrote “Heather Has Two Mommies,” a book that is considered by many as one of the first LGBTQ board books. Kushner remembers how emotional she got while reading another book of Newman’s, “Gloria Goes to Gay Pride,” where the Jewish author briefly mentions Gloria celebrating Hanukkah.

But a lot has changed since “The Purim Superhero” was published nearly a decade ago. Gay marriage is legal — thanks to, in part, amazing Jewish couple Edie Windsor and Thea Spyer (who deserve their own children’s book, too!). There are a lot of incredible queer board books for kids. We’ve got so much more queer representation on TV and in movies, including trans and nonbinary characters. And things have definitely changed when it comes to queerness in the Jewish world, with b’nai mitzvahs and gay weddings being preformed more and more frequently, and many more congregations led by queer rabbis.

“Ten years ago, there was a lot of resistance within Jewish communal institutions to our working with staff who worked with kids who were younger than high school. There was very much a sense that it’s never going to be appropriate for middle school teachers or elementary school teachers, or certainly not preschool teachers, to talk about anything LGBTQ,” Klein recalled. “And certainly, there was a bar against us ever presenting or facilitating anything directly with younger kids.”

“There was a lot of rhetoric that reflected assumption of gayness as a contagion,” Klein added.

But now, things couldn’t be more different. “We do tons of work with JCC preschools and summer day camps with the younger kids — there’s really been an opening up there,” Klein said.

With all these amazing pushes toward progress, “The Purim Superhero” remains a bit of a lone pioneer. After its success, Kar-Ben reached out to Keshet to publish the runner-up for the competition — “The Flower Girl Wore Celery.” But since then, there haven’t been many explicitly Jewish, explicitly queer board books (even though there are quite a few middle grade and YA queer Jewish novels). There are some from independent presses, and some that show LGBTQ characters in passing, but not a lot that center on a queer Jewish family, and none that show trans or nonbinary individuals.

I asked Klein if Keshet has any intention of helping fill that particular void now. “I think the assumption is that at this point, there’s enough momentum in the world that it’s going to happen, and likely it won’t need to be a handheld process by us,” she said.

But not everybody is happy to see this change. With bans on books that retell the story of the Holocaust and LGBTQ books — and the state of Texas threatening trans families — in certain circles, the dialogue of gayness as a contagion remains.

“I feel like we’re living in a time, and maybe it always feels like this for every identity group whose liberation is not complete, where we have multiple, contradictory realities,” Klein said. “There’s a reality in which there’s increasing representation and awareness and all sorts of wonderful engagement. And then there’s a parent of a trans teen in Texas who is now on administrative leave because the state is investigating her and her husband for child abuse.”

There has been one significant change, at least when it comes to “The Purim Superhero.” In the Jewish circles it was intended for, it’s completely uncontroversial. That wasn’t always the case.

When the book first came out, PJ Library, an organization that sends out free Jewish books to kids, decided to have its readers “opt in” to get the book — as in fill out a special form to receive it, instead of sending it to everyone on their list.

“How does PJ Library select books that respect the varied interests of its parents without offending some and disregarding others?” a blogpost on PJ Library’s website explaining the decision read. “We think many families would love this book. Yet we know that there are some parents who would want to decide for themselves.”

While a few families opted to drop their subscription following PJ Library’s decision to offer the book at all, a good portion of the outrage came from the other side — parents angry about PJ Library’s choice to “other” the book with an opt-in. An op-ed from mom Victoria Steinberg in eJewish Philanthropy sparked much of that outrage, and the book quickly sold out.

This year, all kids in the 4-year range got “The Purim Superhero” from PJ Library just in time for Purim, no need to opt in.

The wonderful thing about “The Purim Superhero” is how well it still holds up today, and the wonderful interpretation of the Purim story it offers.

“Queen Esther saved the Jews because she didn’t hide who she was,” Nate’s Aba (Hebrew for father) says in the book. “Sometimes, showing who you really are makes you stronger, even if you’re different from other people.”

Nathan Render, a Jewish dad of two living in Ohio, loves having a book that shows a family just like his, with two dads. They “read it ad nauseum for many days in a row,” he told me, only lamenting that the book doesn’t exist in a hardcover version. “Our book is so used that it’s ripped.” And isn’t that the perfect mark of a great children’s book?