March, 1942. With Poland under Hitler’s regime, Erna and Fela Dranger’s parents thought it best to send their Jewish daughters to safety in Slovakia, which wasn’t yet occupied by Nazi Germany.

But it turns out Slovakia wasn’t safe at all.

Instead of finding refuge, Erna and her cousin, Dina, were among 997 young women in the town of Humenńe who were tricked into boarding the first official transport of Jews to Auschwitz. (Fela Dranger had relocated to Bratislava at that point, but she would later be sent to the camp.) Announcements plastered across the town ordered all unmarried Jewish girls up to age 36 to report to the local school for what was billed as a few months’ work for the government.

Instead, the Slovaks sold these young Jewish women to the Germans for a pittance. And soon, they’d be on a train, being sent to build what would become the Nazi’s most notorious concentration camp.

Oddly, the fascinating story of how the first transport to Auschwitz consisted exclusively of young women has not been told — until now. Erna and her cousin, Dina, are two out of a handful of Jewish girls who survived their experience at Auschwitz from start to finish.

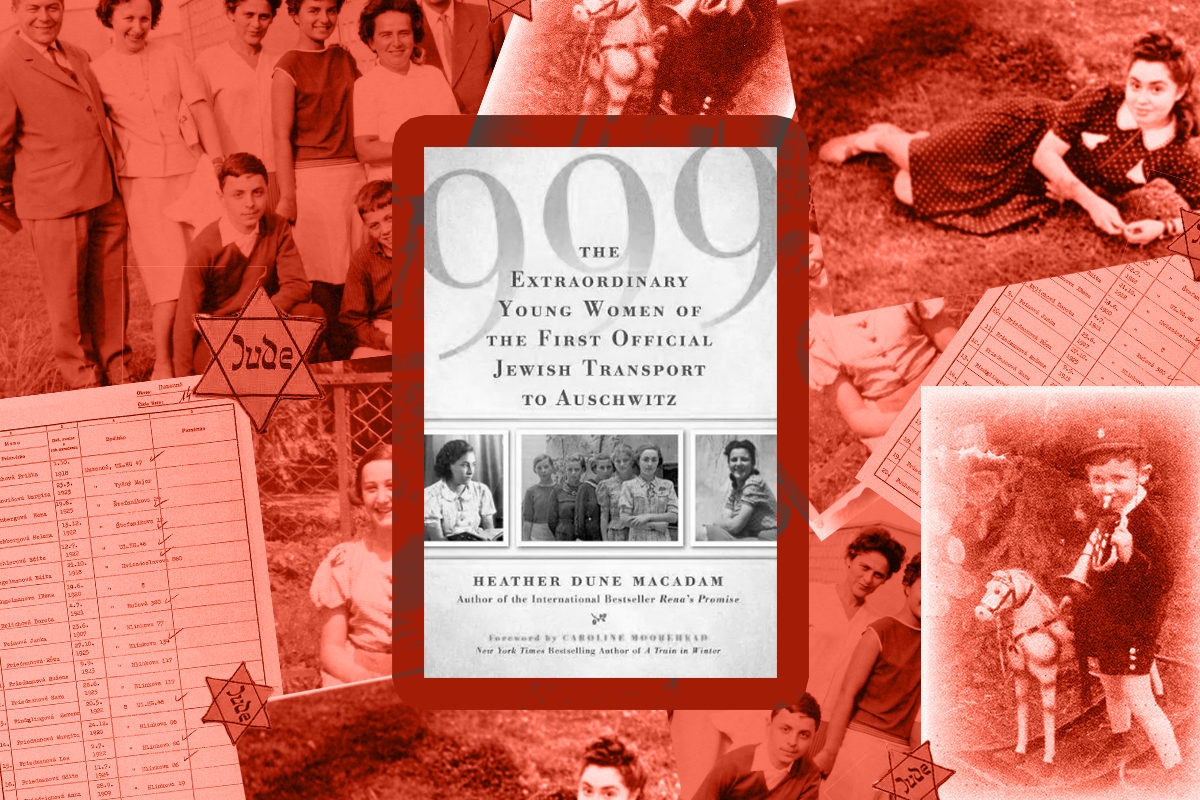

Now, 75 years after the liberation of Auschwitz, author Heather Macadam is recounting these women’s stories in her new book, 999: The Extraordinary Young Women of the First Official Jewish Transport to Auschwitz.

Just why did Hitler begin his “final solution” with women? Well, as Macadam explains, Nazi Germany’s goal was to eradicate all Jews — which meant eliminating future mothers was good place to start. Through extensive interviews with survivors and by examining historical documents, Macadam illustrates what being a teen at a concentration camp was like, and describes in grave detail the horrors of the Holocaust and what it took to survive.

In an email interview, Macadam — who has a Quaker background — told Kveller what intrigued her about this story, why it’s never been told before, and why the book is intriguingly called 999.

Why did you feel compelled to tell this story?

First, I was a teenage girl — I know what it is like to live in a world where you are treated as if you are unimportant simply because you are young and female. As Edith, the main survivor who I worked with, says, “We weren’t adults. We were still young enough to want to throw temper tantrums, to be lazy, to shirk a duty or sleep late.”

I want justice for our lost girls. It is horrible enough that they had to go through what they did, or to have died without anyone ever knowing who they might have become as adults, but to be almost completely be passed over by history for the past 75 years, rarely making even the footnote? That is unacceptable to me.

Second, I am a woman. I think of this as a universal story of sisterhood, bravery, and courage. It shows the best of womanhood, as well as the worst. I think both are important to examine. Edith says, “Some people say angels have wings. Mine had feet.”

Why has this incredible story remained untold?

Your guess is as good as mine, but I think it has a lot to do with the fact that women’s stories have historically been underrepresented. We were considered second-class citizens for much of the 20th century, and we were more likely to defer to men when they told their stories.

The son of the woman whose main narrative I follow through the book, Edith Grosman, says that after the war, when they were living in Prague, survivors would come together at night and everyone would tell stories about the camps, except for Edith. “It was usually my father who did the talking in our family, and his war experiences — though harrowing —were not as scary as my mother’s… I never heard my mother speak about her Auschwitz experiences directly.”

I think that was the case for many women: They would speak to each other, but rarely to others outside their small circle of friends who were also survivors. The other point is that Holocaust history has largely been owned by men — well-educated, wealthy intellectuals. These girls, in particular, were mostly uneducated — unless they went to business or secretarial school. Many were teenagers who hadn’t finished their studies because the government forbade it. Until this year, no one in our world has thought teenage girls had much to say. Now we have Greta Thunberg speaking at the United Nations!

The book is called 999 but only 997 women were on the train. You noticed this mistake in German documentation — did that surprise you?

The standard phrase over the decades has been that there were almost one thousand young women on the train. I thought that was intriguing. Why 999? I spoke to a few historians and learned there was a rumor that one girls escaped, so I thought if I typed up the lists — there are two, a transport list and an arrival list. The girl who escaped would be the one name that wasn’t on the arrival list. They all matched, so no one escaped. And there were only 997 names on both of the lists!

So I began to look at each page, very carefully. One page has pencil corrections and re-numbering on it. Another page has the same number typed twice. Voila! It was a typographical error, or was it?

But there is another reason why I call the book 999, and that is Himmler’s infatuation with astrology and numerology, which readers will discover when they read the book.

The Nazis were known to keep meticulous notes during the Holocaust. Why weren’t there any from the first transport of women?

Meticulous but convenient. And we have to make your question plural – transports of women, and women in general. The fact is that death records for women were not kept until August 1942, or if they were, I never found the documentation. So, there is a record of two women dying within 48 hours of the first transport’s arrival in camp. And then there is no record of any other woman dying for months! Now we know that is simply wrong. It’s impossible because survivors saw girls die.

We also see in the historic record instances of suicide. Grabbing the electric wires was one way to put an end to the misery of Auschwitz. If a man was found on the wires, his name and number were written into an accounting of the prisoners. If a woman’s body was found nothing was recorded: no name, no number. She simply disappeared into oblivion.

What was it like to talk to survivors and their children? Was there a particularly difficult moment?

It is an honor. Always. Not everyone wants to speak with me and I understand that. Some people did not want to be part of this book and I respect that. Others are like my family now.

As for difficulty? I have to say, my feelings are not important. When I interview a survivor it has to be their feelings. I am there to listen. Witness. Receive. Help them bear their burden. It is never about me. The most important thing I can do is keep the focus on the survivor and not think about myself.

What do you want people to take away from 999?

“War serves no one.” That is Edith’s message. Her caveat will break your heart: “Is anyone listening to me?” Just say, yes. And listen.

Images courtesy of Lou Gross; Benjamin Greenman family; Juraj Levicky