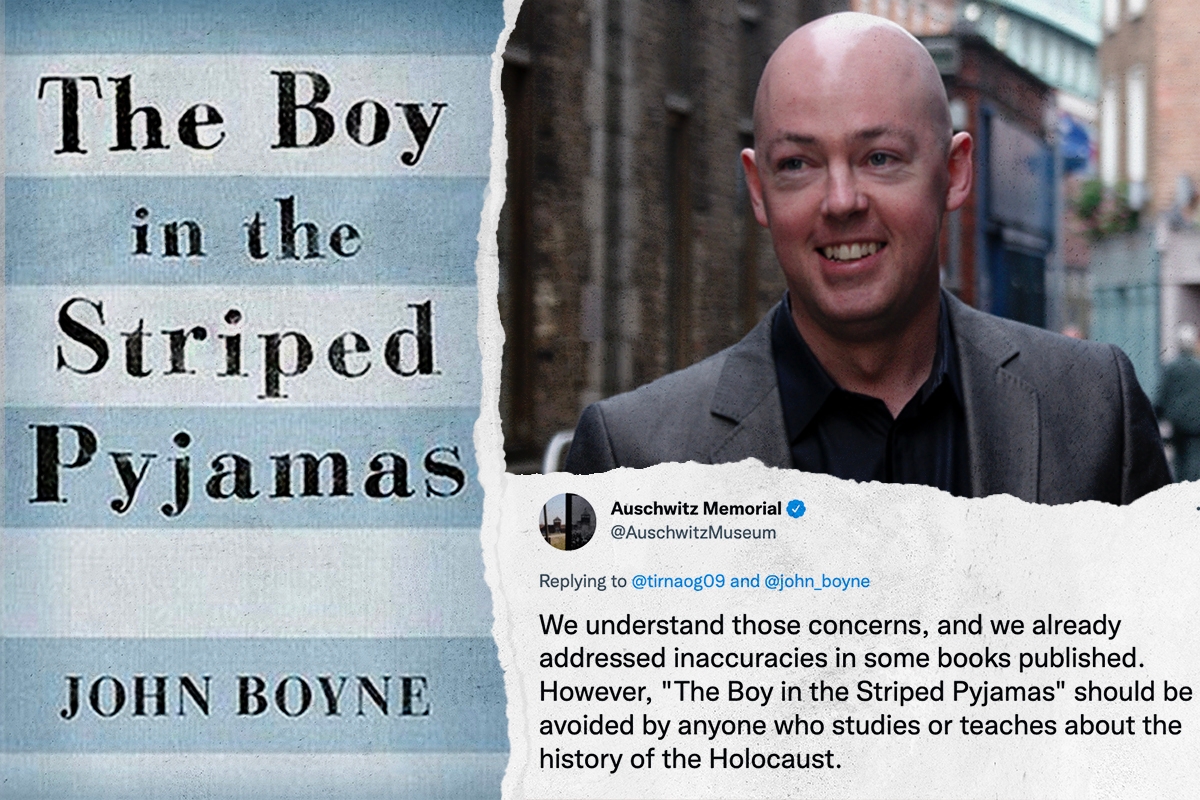

It’s hard to imagine a worse response to a piece of Holocaust fiction than a public denouncement from the Auschwitz Museum. Yet that’s exactly what happened to John Boyne’s 2006 New York Times bestseller, “The Boy in the Striped Pyjamas,” aka The Boy Who Set Back Holocaust Education By Decades.

I can only imagine the Auschwitz Museum is gearing up for their next public denouncement, with the news that the author is coming out with a sequel to the book later this year.

To summarize the plot of “The Boy in the Striped Pyjamas” for you, 9-year-old Bruno, the son of a Nazi Commandant at Auschwitz, befriends a Jewish boy named Shmuel through the fence of the camp. Bruno has no knowledge of the Holocaust (his mother and sister are also unaware of the extent of the atrocities) and thinks Shmuel’s uniform is a pair of pajamas. After Shmuel’s father goes “missing,” Bruno sneaks into the camp to help find him, but the two boys are herded into a gas chamber and killed. Wracked with guilt, Bruno’s father allows himself to be taken prisoner by the allies when they liberate the camp.

Let’s start with some obvious issues. Clearly, Bruno and his family would have absolutely been aware of the Holocaust. Bruno, like all German children then, would have had a hatred of Jews bred into him at school — especially as his own dad was a high-ranking Nazi. Framing all civilians as “unaware” absolves them of any blame, when in reality the majority stood by and watched. Secondly, Shmuel wouldn’t have survived long enough to meet Bruno. Too young and weak to work, he would have been killed on arrival at Auschwitz — days of conversation with a Nazi child through a fence would have been impossible. It might be fiction, but it’s based on a real event. By teaching children that Auschwitz inmates were unguarded and unaware of the constant danger they faced, this tragedy is minimized to an absurd degree.

Want more articles like this? Sign up for our newsletter!

But the thing I find most upsetting is the tearjerker moment over Bruno’s death. Shmuel’s living conditions, his family’s destruction and his father’s murder are apparently not tragic enough for Boyne to serve as the climax of his fable. Shmuel is just a two-dimensional plot device, devoid of personality, present to advance Bruno’s story and provide a Nazi redemption arc. We’re left with the twisted moral that the accidental death of a single non-Jewish child is somehow “comeuppance” for the deaths of millions of Jews.

This book has single handedly set back Holocaust education by decades. According to a study by the UCL Centre for Holocaust Education, it is many children’s first introduction to the topic — they study it in English class before tackling Nazi Germany in history. The same study found it is the most widely read book about the Holocaust among students aged 12-18, surpassing Anne Frank’s Diary (by a shocking 59.1%) and even history textbooks. In the UK, over 35% of teachers use it as a resource when teaching the Holocaust in history classes. The damage it has done is well documented; a 2009 study by the London Jewish Cultural Centre showed that 70% of readers thought it was based on a true story, and many even thought Bruno’s death ended the Holocaust. The UCL study concluded that the book’s use in schools helped to foster “an inaccurate perception of German ignorance of the Holocaust.”

Boyne protests that his work is “just a fable,” but this doesn’t detract from the views of children after reading the book, many of which are quoted in the study mentioned above. “We always think of the Nazis as the bad guys and this shows that the Holocaust didn’t just affect the Jews (…) but the problems that Nazi families might encounter and what their problems were,” said Dan, a year 9 student. “It is too easy to feel sorry for the Jews (…), I don’t mean that in a rude way, it is just like, everyone is always (…) going to sympathize with the Jews (…) when you see it from like Bruno or the mother’s perspective it seems a bit different because they had to live with that,” said Jack, year 12. The most egregious quote though is “they (the Nazis) couldn’t do anything about it because they (…) basically got killed off if they didn’t do what he (Hitler) said (…) it doesn’t matter who was the bigger victim, they (Nazis and Jews) were all still victims of Hitler’s control in some shape or form,” from Erica, year 11.

How has a book condemned by countless leading authorities (Holocaust historians, rabbis, Jewish cultural centers and the Auschwitz Museum) sold over 11 million copies, been translated into 57 languages, and become one of the most widely read Holocaust resources? Perhaps because it wraps the Holocaust into such a nice, simple bow, making it all much more palatable than the reality.

When accused of promoting historical inaccuracies, Boyne has claimed that fiction doesn’t need to be accurate. However, when criticized for his lack of research and subject knowledge, he’s insisted that he’s a longtime “serious student” of Holocaust-related literature who knows the history despite having made an endless string of errors. Rather than admit he might have done something wrong, he’s publicly argued with the Auschwitz Museum on the topic of the Holocaust instead.

Now, in 2022, Penguin Random House is giving us the sequel no one asked for. In case we didn’t get enough of humanizing Nazis, “All the Broken Places” will tell Bruno’s (now adult) sister’s story, focusing on the trauma she feels over her Jew-hating, Hitler-loving past. Why? It seems a poorly thought out, cash-grabbing sequel is more important than proactively making amends for the damage already done to the Jewish community and Holocaust education. Deciding to publish this means actively ignoring the multiple concerns raised by leading authorities.

When Boyne’s book comes out this September, I urge you not to read it to your children. Instead, teach them about this tragic aspect of our recent history through valuable resources like “Night,” “Maus,” “The Diary of Anne Frank,” “Hana’s Suitcase,” “Eva’s Story” and the many other real stories about real Jews, who describe the Holocaust as it happened. They may be more painful and less palatable, but that’s OK. Genocide shouldn’t be an easy topic anyway.

Like this article? You may also be interested in:

How Do You Teach Kids About the Holocaust? Not Like This.

This May Be the Best First Holocaust Movie to Show Your Kids