Taffy Brodesser-Akner is used to being the interviewer, not the interviewee.

“I’m very used to constructing myself in words privately,” she tells Kveller. “To suddenly just be talking, and for it to appear somewhere, I haven’t gotten used to it.”

“I’ve always had a lot of sympathy for the people I write about; I always think it must suck to be written about,” she adds. “But now I really know: You have no power.”

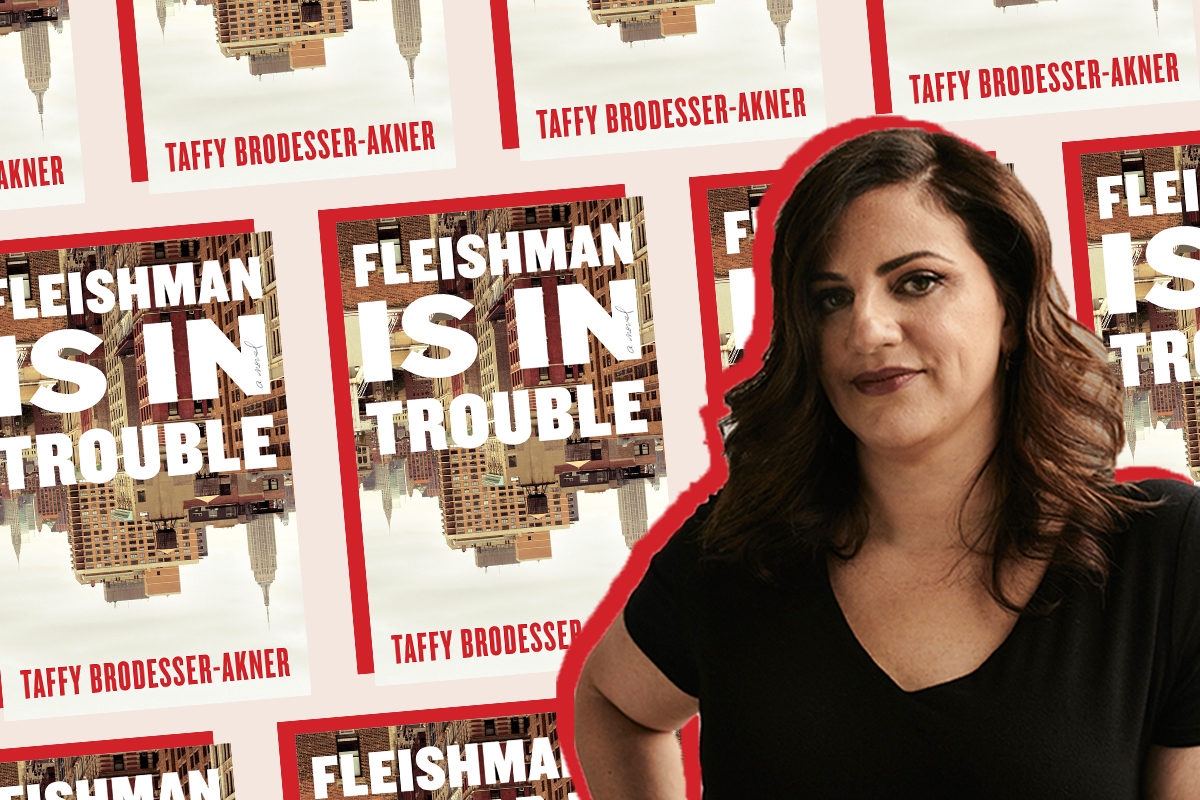

You may know Brodesser-Akner from her celebrity profiles for the New York Times — of Gwyneth Paltrow, Tonya Harding, Bradley Cooper, and more — but now you can read her superb writing in full-length novel form, with her deubt novel, Fleishman Is In Trouble.

It’s the story of Toby Fleishman, who — you guessed it! — is in trouble after his wife, Rachel, disappears a few months after their separation. It’s a story of a Jewish family, divorce, motherhood, and so much more. And it’s not told by Toby or Rachel — the narrator is a woman named Libby, who spent time in Israel with Toby during college. I won’t spoil anything else; you should really, really, read it yourself.

I had the chance to chat with Brodesser-Akner about writing Fleishman Is In Trouble, the reaction to her first book, and why she decided to set the story in a world she knew so well.

Why did you choose to narrate Toby and Rachel’s marriage from a third perspective?

It’s how I know how to write. It’s how I do my journalism. I always felt like you should know where perspective was coming from; and then, one day, I started using the first person [in my journalism] to say what I had seen. It opened things up in a way, and it forces you to not be indulgent. It’s a good test if you’re someone, like me, who is afraid of taking up too much space.

So in the novel, at first, Libby was just a third person character. My friend Mark said to me, “Why would you do that when that’s not how you write?” And I thought, well it’s a novel, I have to be fancy! He said, “Would anyone ever tell any of your literary heroes: You have to write differently now because you’re writing a novel.” And once he said that, I started thinking that [the novel] is kind of the same thing as my journalism, it freed everything up.

As you were writing, how did you describe the project to people?

I’m writing a novel about a man getting a divorce.

Did you feel like that’s how it ended up?

I think it is. I [still] don’t know how to describe it! Do you know how to? Can you help me describe it? The other thing I say is: It’s a lateral move from my journalism. It’s a man’s story, which is what I’ve mostly written — I had all those years at GQ. It is a man’s story that I come out of in the end. That’s how it feels.

I can imagine Rachel’s storyline — the traumatic birth she goes through, the struggle she has between working and being a mom — will resonate with a lot of Kveller readers. As a mom yourself, did you relate to those feelings? Did you draw upon experience for that? Which is a lame question, I apologize.

No, it’s not a lame question! I never understood why authors get upset when you ask how they identify with certain characters. Because as a journalist, right, I’m like, what do you want me to ask? What do you think we’re doing here? But now, I especially don’t have patience for it because of course you should ask me where it all comes from. But the answer is, now I know why that question bothered them so much: There is not a clear one-for-one in the experience, it’s too tangled to explain well.

All I can say is: Every thought in there is mine. And I’m sad to say that around the birth, that was my experience for my first child.

When you publish a book, you have to read it a thousand times. As you know from writing, by the third time you read it, you’re like, oh this is a complete piece of shit. No matter how much people will like it later, it’s always a complete piece of shit to you. The birth stuff — even at my last read — I cried every time I read it. As if I hadn’t written it. As if it was news to me. I guess that’s the nature of trauma.

It never gets easier.

No, I wish it did.

How has the reaction to Fleishman Is In Trouble been like for you?

At first, you know, I’m used to this. I’m used to a lot of people reading [my] things and having a reaction. And I’m always nervous the first little while.

The Washington Post review nearly murdered me in my bed, I could not even believe a review could be like that. So I can’t complain. But I can say that I’m extremely emotional in a way that I’ve only been in the lead up to my wedding. And I guess the birth of my children, but I didn’t know when that was going to happen.

Being on the other side of all this press, what do you wish people asked you about in these interviews?

The things I like talking about, they are asking me about. Like, how it’s different from journalism. I love talking about storytelling. It’s been interesting to observe other people telling me what’s interesting about the book. And I love especially when people ask about motherhood. You are the first person to ask about the birth.

No way.

Isn’t that crazy? It’s a very easy thing to find. It’s maybe even on my website, I wrote about it [and it] is what launched my career… I’m so messed up from it. No one’s asked me about it.

And we are a Jewish parenting site, so I have to ask about the Jewishness of it all…

Ask in Yiddish!

The Jewishness felt so embedded in the characters. Why was it important to you to situate the story in Jewish New York/New Jersey?

It’s just what I know. Do you know what I mean? This is a real situation of “writing what you know.” I’m a big fan of specificity; I’m very against making something broad so many people understand it. That’s my experience in writing: the more specific you are, the more people can see themselves in a story even if the specificity doesn’t apply to them. I don’t know why that is, but it’s true.

Even down to the title — which I was worried would exclude a lot of people. Ultimately, it would be false advertising to not say this is what it is. This is a book about a Jew in New York. I like the idea of not explaining what a Friday night dinner is — just having a Friday night dinner. I like the idea of everyone going only to the school where they’re going to meet other Jews like them. There’s still this huge culture around Jewishness, and I’m very comfortable in it.

In your Grub Street profile, you wrote, “I’m raising Jewish children and I grow concerned that I can’t raise them Jewish unless there’s some kind of ritual attached.” Can you expand on this?

We have these Jewish ideals, and my husband and I have gone back and forth on various forms of practice. He converted and he was really into it at first. And then [there were] things he became very upset by — the get situation and agunot. We saw a few of those cases up close, and he felt like he couldn’t stand by and participate in any kind of Orthodoxy that still allowed that to happen. It was a real tragedy for him because he really loved the community we were in — we both did. But we moved, and we’ve struggled with how much ritual do we keep in our lives if we are not practicing in an Orthodox way.

What I found was [that] if there’s no actual action attached to the thing, it’s just all theory. I could be a good liberal [but] if I don’t volunteer somewhere for my children to actually see, I’m not transmitting that value. I’m just talking. Kids get to a certain age, and they don’t listen to talking anymore.

But my children know that there are no screens on Friday night and on Saturday. My children know that we’re always together during those times. My children know that we visit our friends, the Zacks, in Los Angeles for Pesach. Like those are things that they need to see. That’s the work. You can’t just talk about it. And sometimes on Friday night, all I want to do is watch a movie with my children. It’s the only thing I want to do and I don’t ever do it. Because once we lose the sanctity of a ritual, it’s gone.

Image of Taffy in header by Erik Tanner.