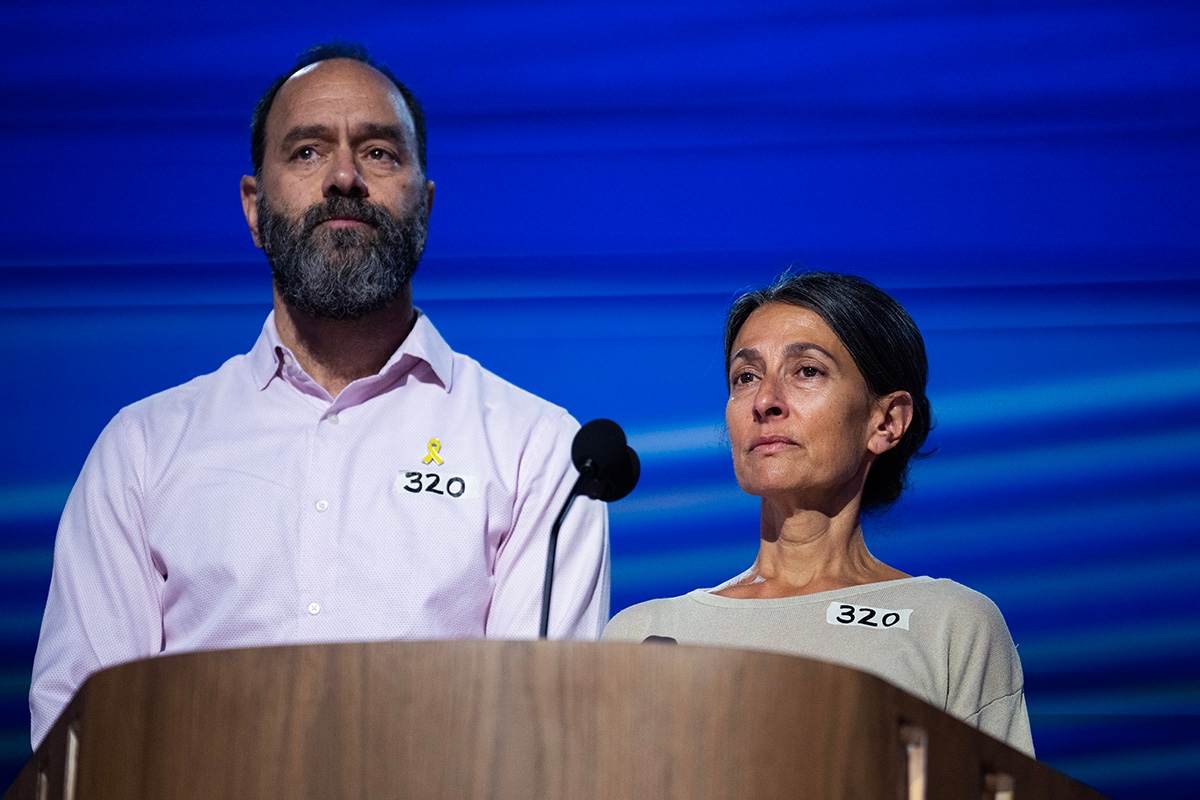

It’s hard to believe it, but it’s now been over a month since the slain bodies of Hersh Goldberg-Polin and five other hostages were discovered by the IDF in a tunnel in Gaza. In a recent interview with Israeli news channel 12, Hersh’s parents, Rachel and Jon Goldberg-Polin, opened up about what this time has been like, sharing harrowing details about how Hersh’s body was discovered and musing about what true “teshuva,” redemption, would mean when it comes to their son.

The concept of teshuva is at the center of the High Holidays, especially Yom Kippur, which begins on the evening of October 11 this year.

“I found it very interesting that people in power tried to come to us during shiva,” Rachel said in the interview. “We actually said, ‘Please, we don’t want those people here.”‘ She added that the message was relayed in a kind way, but that they didn’t want to hear any apologies from anyone in leadership, as they were not the ones who could grant them forgiveness.

Rachel then referenced the Torah portion Vayikra, which “talks about when you do a sin intentionally, you bear the punishment for that sin. Don’t come and ask me to forgive you for that sin. I’m not the right address.”

“Real teshuva,” she added, comes when someone finds themself “in the exact same situation where you did the thing that you know was wrong, and you choose differently.” That, she said, is what she “would challenge those people who wanted to come to us after they chose not to save the six. You have 101 chances now — do it, and that’s teshuva. You don’t have to come to me and ask for it.”

The interview was full of moments too harrowing to bear, and yet they are the Goldberg-Polin’s, and to a larger extent, the people of Israel’s, truth. Jon recalled how in the many meetings with people in power, they kept saying that they’re “lacking urgency.”

“Why are you confident that we have time and that this isn’t going to lead to a situation where too much military pressure at the end of the day leads to captors lining up hostages, shooting them one by one in the head?” Jon said they had asked long before exactly that happened to his son and five others. To that question, Jon says they were told, “No, no, it’s not going to end like that. They’re an asset. There are reasons why it’s not going [to end] in that way.”

Rachel said she’s worried that the hostages’ families own optimism, their positivity during such a dark time, “made the people who were at the table and the people with power believe everyone’s coming home.” But now, beyond the shadow of a doubt, she says, they know that “there is not one second to waste. We need to move now. There are people today, as we’re sitting here talking, who are in those same conditions, and it’s probably gotten worse.”

“I’ve learned so much in this crash course over this last year about the game of politics,” Rachel said. “I do think it’s a game, and we were pawns in this game, and the hostages are pawns, and Hersh was, and as anyone who plays chess will tell you, pawns are expendable.” Jon, too, talked about losing his faith in the political system: “Something went awry in the decision-making process here,” he said, saying that he thinks that previous Israeli leaders would’ve acted differently. “I’m having trust issues with anybody, anywhere in the world lately… I think we deserve to have that skepticism.”

Hostage families, Rachel shared, are often “made to feel that they’re speaking in a clichéd, hysterical way,” adding that “in a world where the only way that people communicate is screaming… we found that it was useful not to be screaming. But at a certain point, when you’re in so much pain, I do wonder when are we allowed to raise our voice? And so I would like to ask permission: Now that my person is not there, am I now allowed to be considered? Is my voice more valuable now that I don’t have a child in that situation anymore?”

Rachel’s message to the world is this: “The hostage families have given you 367 days. You have not succeeded. Something’s off. Maybe it’s time to mix up the dynamic of who is doing this, so there’s room for people to be really focused on the north and on Iran and on things that are happening in the shtachim [territories] 100%… but there’s also room for a few people to be constantly keeping their finger on the most life and death issue we have control of, which is the hostage issue.”

The Goldberg-Polins said they were surprised by the amount of people who came to Hersh’s funeral, seeking to comfort them but also to be comforted themselves. “The country is traumatized,” Jon shared. “When those six deaths were announced, of vibrant young people who I think all of us believed they’re coming home… It was just such a complete fall that people need repair, and one way they’re doing it is to reach out to each other, reach out to us, reach out to the other five families. And I think that nationally, collectively, maybe we’re hoping that it can be catapulted into something good.”

“Those beautiful six, Alex and Ori and Almog and Eden and Carmel and Hersh,” Rachel said, referring to the hostages who were found killed with Hersh, “kept each other alive for months and months and months in conditions that are just unimaginable. They did every single thing right, and we, all of us, failed them, and people were completely broken. It’s all of us. It’s all six families just getting this complete outpouring of fractured, fragmented pain.”

Rachel talked about the terrible kind of fame she’s been thrust into, and how it’s not been easy for her. Her forbearance, eloquence and strength have made her into a symbol, but one she never wanted to be. She said she’s always loved having a Jewish generic name, Rachel Goldberg, and looking like so many dark-haired Jewish women — “I’m the Jane Doe of Jewish women” — and that it has been difficult to deal with her face and name now being the trigger for so much pain to others.

Perhaps the most painful moment of the interview was when Rachel talked about how the hostages were found. Hersh, who was almost six feet tall, was emaciated, weighing just 116 pounds, his body riddled with bullet holes. Hersh had tried to protect Eden Yerushalmi in his final moments; he was found on his knees, with Eden’s head on his lap or side, a bullet through the hand that tried to fend off the shots, and more in his head and shoulder. The tunnel they lived in had bottles filled with dark urine that showed how dehydrated they were. “Just a nightmare,” Rachel said.

Rachel and Jon also talked about how to move on through their grief. “I had him for 23 years and three days. Then he went to the Nova and he was stolen from me and from Jon and from his life and from himself for 328 days.” She added, “I want to believe now he is OK. And the question is, how do we become OK? We are going to heal. You can heal and go through life feeling blessed that you had that person when you did have them.” She talked about how there are people who walked out of Auschwitz, who never forgot their perished loved ones but went on to find joy and family and love, who went on to have a good life. “And there are people who walked out of Auschwitz and never left Auschwitz,” she said.

“We’re in mourning. We’re suffering. But we are making a choice personally that we are going to live life. We need to do it for ourselves. We need to do it for our daughters. And we need to do it because Hersh would want us to,” Jon said. “So we will live life.”

You can watch the whole interview here: