In her musical comedy special “Death, Let Me Do My Show,” now streaming on Netflix, Rachel Bloom reminds us that she is an atheist on multiple occasions. She doesn’t believe in God; she doesn’t believe in the afterlife. Yet, as she says in one anecdote about her 2020 labor and her daughter’s NICU stay, “I am still a Jew. And as we all know, the real God of the Jews is any doctor.”

Bloom has given many nuanced contemplations about Jewish identity — and stereotypes — in the past, including struggles with mental illness and overbearing mothers in her series “Crazy Ex-Girlfriend” and an album full of lyrics about Jewish overachievers and neurosis in “Suck It Christmas!!! (A Chanukah Album).” And though that seemingly throwaway line about doctors is her new special’s only Jewish line, its grappling with death, how it meets us in life and the murky idea of what comes after it, will feel profoundly familiar to any Jewish person.

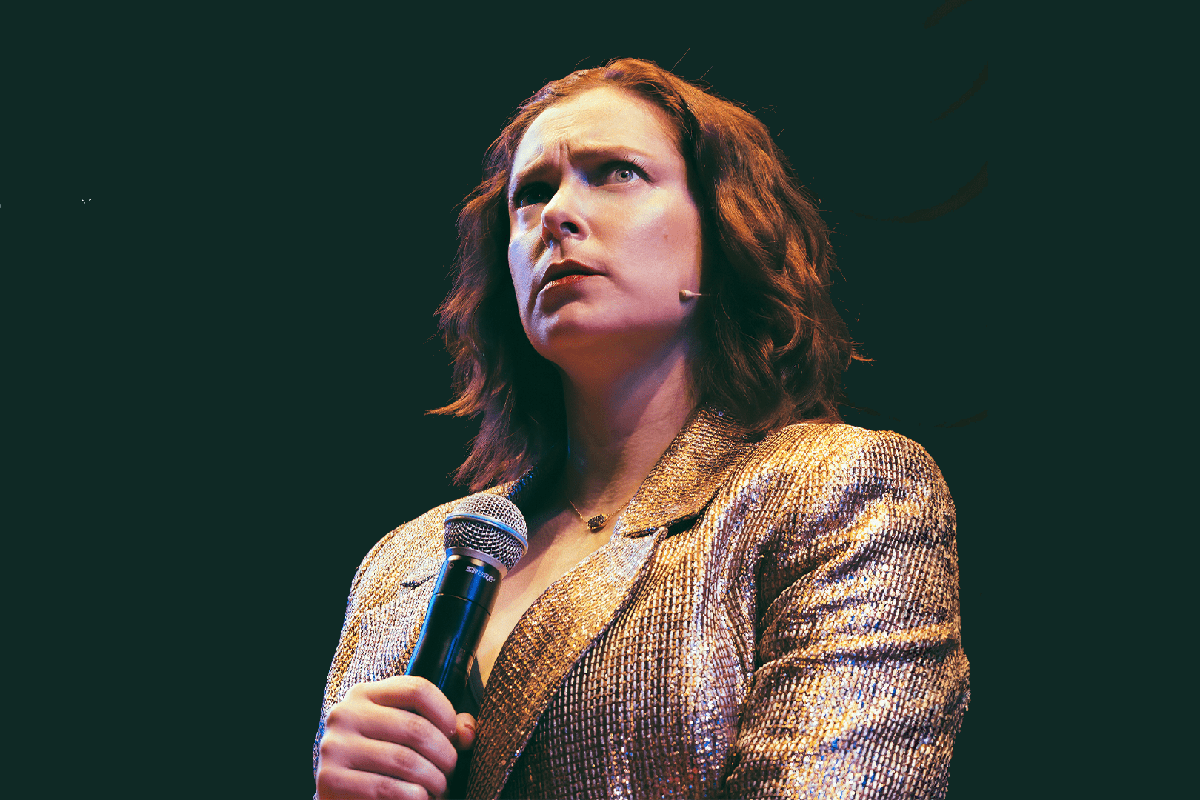

The premise of this wonderfully funny and deeply felt show is this: Bloom gets up on stage, ready to perform a show that she wrote before the pandemic. She starts by singing a very Bloom-like song about the Bradford Pear Tree, which, at times, smells like semen. “Meet me under the cum tree,” she croons Broadway-style on a stage in Massachusetts in March of 2024. But then, she gets heckled, literally, by death, personified by her “Crazy Ex-Girlfriend” co-star David Hull. Death won’t let the singer and showrunner do her show, but interrupts her until she confronts it, ultimately making death a part of her show. What ensues is a performance that weaves death into it in every kind of poignant and diverting way.

The Jewish approach to death, to grief, is all about making place for it in life. In the year after loss, Jewish mourners have rituals to literally walk them through the process of grief, from the shiva to the shloshim to the Yizkor and saying Kaddish. On the most important Jewish holidays, we light Yahrzeit candles to remember our dead. And most holiday celebrations themselves are confrontations with our own mortality in history — “they tried to kill us, we survived, let’s eat” is the famous summation of most of our holiday stories.

Bloom’s show can be summed up similarly: “Death is at every corner, I survived, some didn’t, let’s laugh.” Oh, and let’s also sing, an important part of Bloom’s shows and Jewish holidays, too.

Death first made its presence un-ignorable in Bloom’s personal life at the same time that it did for many of us, near the start of the 2020 pandemic. Not just because of COVID, to which she lost her collaborator, musician Adam Schlesinger, a loss that four years later she still struggles to come to terms with on stage, but because that was when she was giving birth to her child. Childbirth is often an act that confronts a parent with the terrible idea of mortality, but for Bloom specifically, when her daughter was born with fluids in her lungs, it led her, as it does for many parents, to an endless spiral of anxious googling in which one gradually discovers more and more of the long list of things that could potentially kill our children.

The night after streaming “Death, Let Me Do My Show,” I have a close call of my own with my youngest child. It was the kind of accident where you see how an extra minute of inattention could change your life forever. In the hours and day after, I feel like I’m Bloom up on that stage, being heckled by death, being forced to confront it. “I’m anxious every moment of my child being hurt or dying,” Bloom told Kveller in an interview last year during her show’s run in New York. How could you not be anxious, she rightfully claimed, when “you’re raising someone who is actively trying to kill themselves at any given moment.”

In the show, Bloom is periodically chanting “please don’t die,” a literal refrain of a parenting song that Bloom sings on stage, full of so many little details that feel familiar to any anxious parent (hair tourniquet syndrome, anyone?). As Bloom says, a child is “a thing that will ruin you forever if it stops,” and a parent’s most important wish is never ever to outlive one’s children.

“I have to imagine worrying about death is quintessentially Jewish just because of — from what I know about epigenetics — it’s the nervous ones who survived… if you’re not paranoid, you didn’t survive because people were always coming to kill you for most of human history,” Bloom mused to Kveller last year.

Another song Bloom sings is about the concept of the afterlife, or, well, the concept of the afterlife in relation to her dog, whose mortality is the first she was worried about back in 2020. The song is about the concept of the rainbow bridge, which Bloom says she finds comfort in even though she is an atheist who doesn’t believe in heaven. This kind of contemplative vacillation about faith and life — she doesn’t believe in the afterlife but she takes comfort in it as a concept; she doesn’t believe in God but she has conversations with him when things get dire; she doesn’t believe in ghosts or psychics (they killed Harry Houdini, she claims) but she does go to one to try to find a connection with Schlesinger — is profoundly human, relevant and a part of Jewish tradition, which asks more questions than it answers, especially about the concept of the afterlife which is a bit more murky and undefined in comparison to other religions.

Some of the best numbers of the show, the funniest, are in its literal confrontations with death. On multiple points, Hull takes the stage for musical numbers. In one devastatingly hilarious moment for musical theater fans, he compares himself to the protagonist in “Dear Evan Hansen.” Death is basically that kid in high school who nobody sees but is always there.

No one does musical comedy quite like Bloom, and the numbers in the show are all brilliant, joltingly funny and original. And through the laughter, Bloom doesn’t shy away from the biggest questions about life and death: What if there’s nothing after life? What if there are no ghosts? What if this is all we have? Why is death so horrible, scary and always there?

“Death, Let Me Do My Show” looks unflinchingly at death, at the way it is an inextricable part of life, and ultimately finds a way to make peace with it, or at least to make beautiful comedy and music that stares directly into the abyss and leave us with more meaning.