Our synagogue in Seattle has never closed its doors on Shabbat. Yet this past weekend, alongside a slew of public events indefinitely postponed, Shabbat services were canceled due to coronavirus. Then we received word that the Purim celebration on Monday night had also been called off.

My oldest child, age 10, had been practicing for weeks to perform in a special Purim Ma’ariv service before the megillah reading, with choreography and prayers creatively set to tunes from The Greatest Showman. We’ve been told that the performance, which annually packs the entire sanctuary with costumed audience members, will be held at some future time, whenever we’re allowed to gather once again.

The Jewish community isn’t the only group in Seattle whose plans for a costumed gathering have been thrown into disarray. Among the many cancelled events in our region is Emerald City Comic Con, which was supposed to take place March 12th-15th. Downtown Seattle was going to be filled with thousands of cosplayers in their finest get-ups, inhabiting the pop culture characters they love best. (When you think about it, a convention center full of Harley Quinns and Hans Solos is not that different from a Purim masquerade.) As of March 9, King County confirmed 116 cases of Covid-19, and several area schools have closed as more exposures get reported.

The cancellations have left me wondering: What exactly is peoplehood when you can’t be together in person? So much of Jewish community is about being in proximity to each other, physical presence a catalyst for spiritual uplift. A minyan (prayer quorum) can’t take place without at least ten people present. In the new era of social distancing to reduce exposure, some public health officials suggest that same number as the upper limit of people who should participate in face-to-face meetings. As Amazon, Microsoft, and other big tech companies tell their employees to work from home, minyan is now risk mitigation.

Alongside other moms in my circle, I’ve watched in disbelief as the public health situation in Seattle and the Puget Sound region has evolved over the past few weeks. The bar mitzvah of close friends’ son took place in late February; the party was joyous, though I noticed more than a few revelers dashing to the bathroom to wash their hands after the extended hora dance. No word yet on the April bat mitzvah of another friend’s daughter, or my nephew’s bar mitzvah in May. Parents are cautiously buying supplies for an unscheduled staycation of unknowable duration. (Is there a TripAdvisor page for that?)

Instead of looking forward to spring, when the notorious gray of Seattle winter slowly gives way to abundant green and sunnier skies, Seattle Jews are uncertain about whether they’ll be able to host Passover seders with other families next month. In the era of pandemic panic, our city’s designation as “the Gloomiest City in America” has taken on a whole new meaning — as has the notion of ritual hand-washing.

And yet, all this unpredictability is oddly appropriate for Purim, that topsy-turvy holiday when nothing is at it seems. Rabbi Ruth Abusch-Magder, writing in the Atlanta Jewish Times two years ago, observes the way this holiday combines the opposing themes of happiness and uncertainty. She notes that the tradition of drinking alcohol until there is no distinction between good Mordechai and wicked Haman “points to the fragility of not knowing where things stand and the potential for reality to change at any moment”— relevant themes for what we are experiencing now in America, as unprecedented measures are being taken to reduce the threat posed by an invisible enemy.

This surreal moment, and the uncertain months to follow, don’t have to be all gloom and doom, though. I’ve read thoughtful, poignant emails from rabbis and community leaders here in the Pacific Northwest and other areas explaining how to partake in the Purim holiday, or how to pray in general, while keeping each other safe at the same time. Our synagogue is setting up ways for the most vulnerable to be checked on, offering pastoral care, and encouraging members to cook extra meals that can be frozen and delivered to those in need in the coming weeks. Care and chesed (loving-kindness) are emerging despite the tension we all feel.

As for Purim, my friends have responded to the strange circumstances of this year’s holiday in different ways. Some posted pictures of the hamentaschen they baked; others couldn’t summon the mojo to bake this year, saying “it just doesn’t feel like Purim.” (As for me, I just salivated over Molly Yeh’s hamantaschen archive). And it hasn’t felt quite like Purim, at least any Purim I’ve ever celebrated. But somehow, as the holiday got underway last night, happiness arrived. Over a text thread, my friends and I shared pictures of our kids in costumes at home; some weren’t dressed up, but piled onto their couch to send out big smiles anyway.

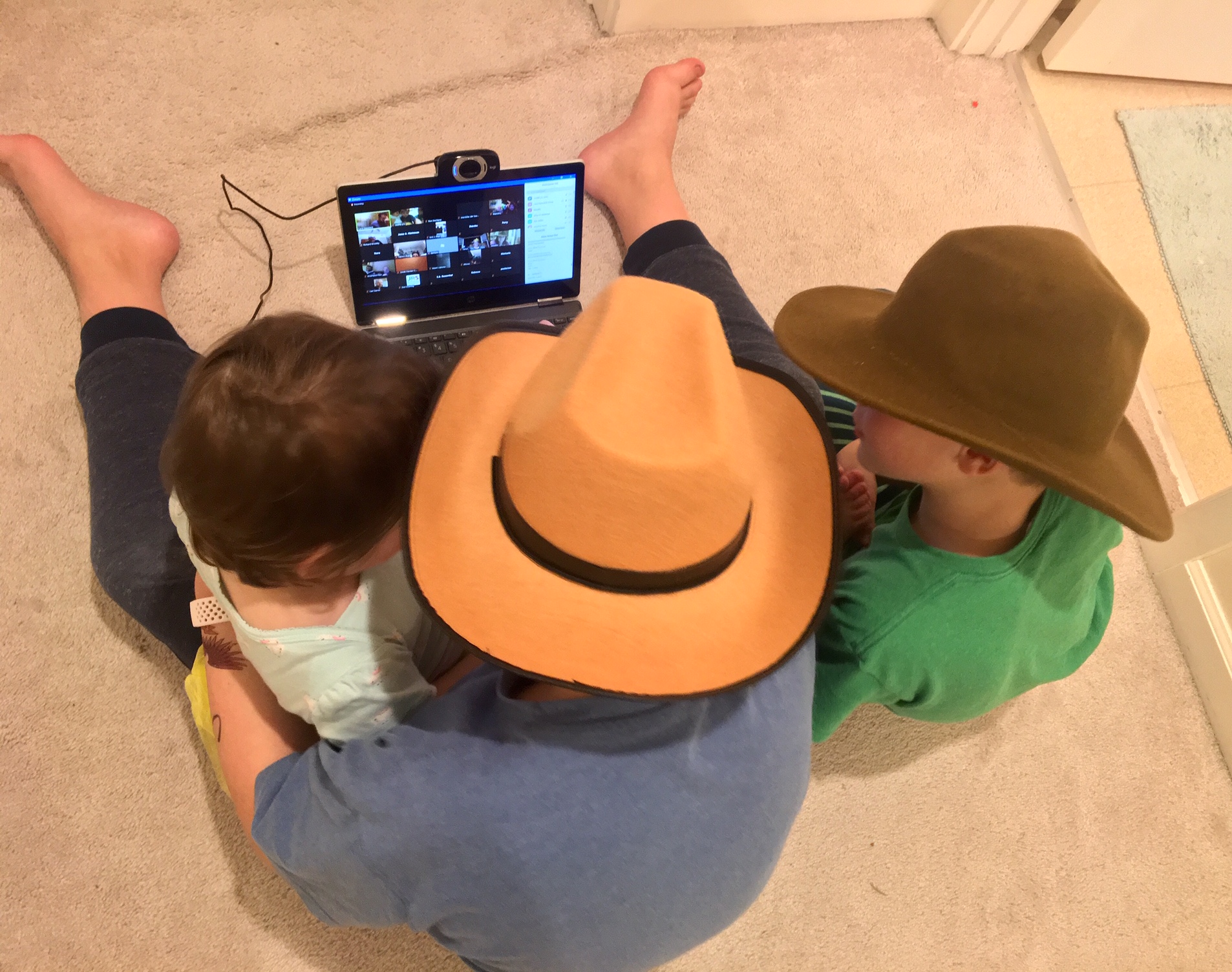

Then, like other communities taking extra precautions these days, we grabbed a laptop and hopped onto our synagogue’s Zoom meeting to hear the megillah reading. As various congregants chanted, a texting option let listeners chat with each other. During breaks between chapters, members of a local klezmer band played soulful music on clarinet and accordion. I adjusted the volume so that I could give my toddler a bath and keep listening; once she was dressed, she donned a yellow tutu and joined the audience. Looking at the Brady Bunch-like mosaic of faces on screen — smiling, clapping, singing, booing enthusiastically when required — I realized that although we were not physically together, we were together nonetheless.

Last night, as we communed online to hear an ancient story, the full moon of Adar rose brightly in the sky. (This year it’s a “worm supermoon”; NASA’s article about it name-checked Purim!) And the fact of the matter is, our community did celebrate Purim together. “It actually was fun and very millennial,” my friend Karey Kessler, an artist and mom of two, told me. “Definitely not the same as being in person – but better than being isolated and alone.”

My son Idan, though still disappointed that he couldn’t perform in the Ma’ariv show, agreed that the group chat was fun, and he was a fan of what he called “the digital Purim costume party.”

Rituals, like the cycles of nature and the moon, can be incredibly comforting in trying times. They place us in the familiar groove of past celebrations; those places, songs, and smells we sense with our core beings. But even the most treasured rituals can’t always mitigate against the uncertainty of the unknown. We’re so used to literally, physically being with others that the world really does feel like it’s been turned upside down right now. In the weeks to come, may we all be able to connect as a community, in whatever ways we can, to find new rituals of comfort and support despite the distance between us. And may next year’s Purim bring more joy and less suffering for all.

Image of children by Hannah S. Pressman; cover image by Jodie Griggs/Getty Images