Light spoilers ahead for “As They Made Us,” “Life & Beth” and “Russian Doll”

I find Mother’s Day strange. Maybe it’s because I didn’t grow up with it — it’s not really a holiday in Israel where I spent my childhood, having been replaced with the pretty uselessly meh Family Day.

But more likely, it’s because, beyond the bouquets and spa days and bottomless brunches (don’t get me wrong — I want, need, and deserve them all, plus some extra Bloody Marys for the road), Mother’s Day makes me think of, well, motherhood: both its ideals and its failings. Not just my relationship with my kids, but my relationship with my mother, and her relationship with her mother, and the messy tangled web of it all. The intergenerational trauma and the regular run-of-the-mill childhood scars that inform our parenting, as well as literally everything else in our lives — you know, the whole delightful shebang that one works through in a lifetime of therapy.

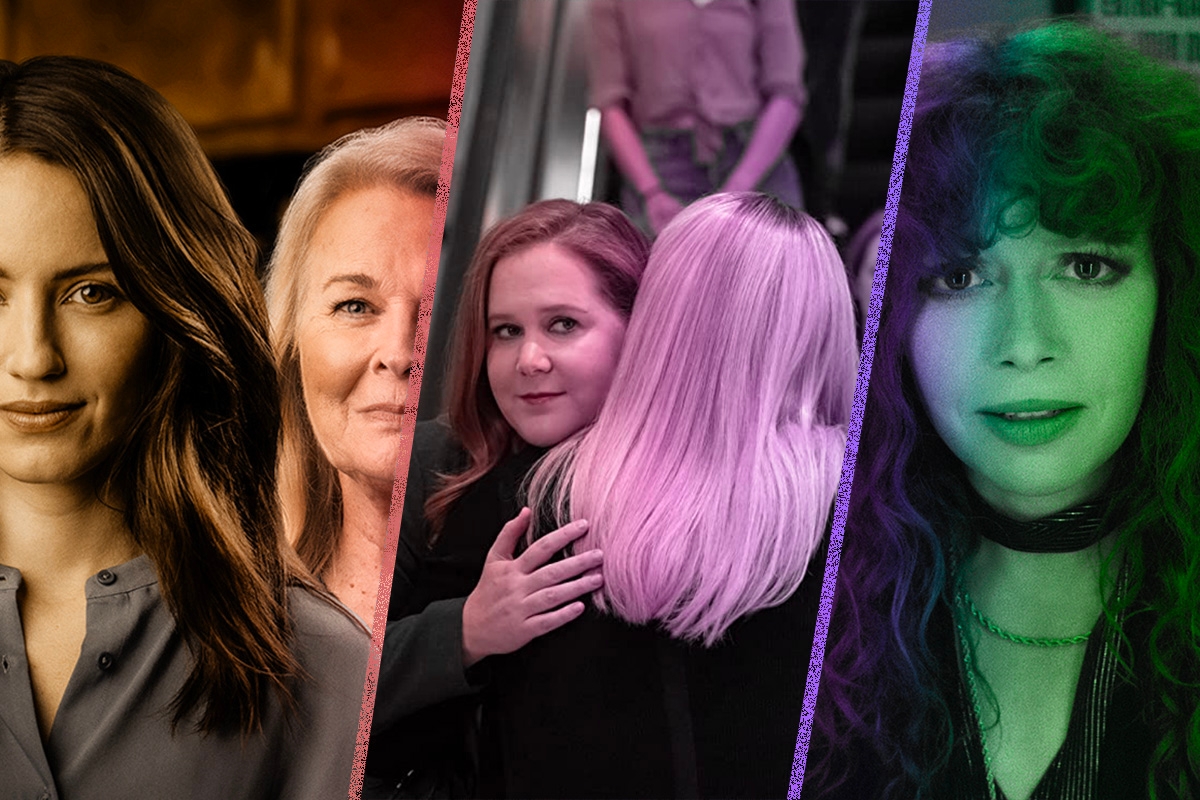

It’s a weighted thing to disentangle, but lately, I feel like I’ve had some help from Jewish TV shows and movies. “As They Made Us,” “Life & Beth” and “Russian Doll” feature Jewish women, and Jewish moms, poignantly excavating those relationships. (To be fair, it feels more like bloody open-heart surgery than the digging up of bones and relics in the dried ground.)

Mayim Bialik’s somewhat autobiographical “As They Made Us” has an apt title for a movie about the burdens we inherit from our parents. It comes from a line uttered by the film’s protagonist, Abigail (Dianna Agron): “you’re as sick as they made us,” she tells her estranged brother, the “they” referring to their parents. In flashbacks to their past, both Eugene (Dustin Hoffman), their father, and Barbara (Candice Bergen), their mother, are shown as neglectful and abusive.

The film centers around the gradual loss of the family patriarch to a degenerative disease, and Abigail’s attempt to reconcile with her brother before her father dies. For Nathan, forgiving his father is easier than forgiving his mother. The way she hurts him, he tells Abigail, is so much deeper and more sinister. When he makes up with his father on his deathbed, he refuses to have his mother present.

Nathan may be right that his mother’s emotional abuse and neglect were perhaps more damaging than his father’s anger and physical abuse (that is, after all, his call to make). But it did make me think about the double standards we hold for our mothers. No matter how feminist we might consider ourselves, we may still be so much more willing to forgive our fathers for their neglect and abuse than we are to forgive our mothers — because more is expected of them.

Amy Schumer’s “Life & Beth,” partly based on the comedian’s life and childhood in Long Island, also shows a portrait of a chaotic childhood with troubled Jewish parents. Like “As They Made Us,” it oscillates between the present day and flashbacks to Beth’s early teen years, opening with the dissolution of her parents’ marriage. But while the show does grapple with Beth’s relationship with her mostly-absent father, it is really centered on her relationship with her mother, Jane, who raised Beth and her sister.

Beth loses Jane in the first episode of the series. That life event, as Beth approaches her 40th birthday, leads her to completely remake her life. The entire season, in a way, documents Beth’s relationship with her mother and the full extent of trauma Jane has caused her daughter — by focusing on her own relationships, by being stuck on ideals she had for her daughter instead of being a supportive mother, by lacking boundaries and in a myriad of other ways. It all ends with a makeshift heartfelt event to eulogize Jane, to make up for the anemic Jewish funeral we see in episode two of the show.

Beth recounts all the fond memories of her mom (“she could make me laugh with just one little expression”) and all the ways she wasn’t there for her (“she lived in her own idea of reality. She lived in her daydreams and that’s how she survived”). “No one loves you like your mom, and no one hurts you like your mom,” she says at the end of the event, though she professes, “I loved her, always I loved her.”

It’s Beth’s sister who sums it up best, really, in a reflection that many daughters would relate to: “Our mom loved us the best she could, and she wanted to be a really good mom, and sometimes she was.”

“Life & Beth” is a coming-of-age tale, and a tale of healing. As Beth tries to move on from her grief and build the life that she wants for herself as an adult, she also finds compassion for her mother. In Natasha Lyonne’s “Russian Doll,” protagonist Nadia Vulvokov experiences a very similar journey, though in a very different way.

The trippy second season of the show sees Nadia traveling back through time this season, inhabiting the body of her mother in the 1980s — and then of her grandmother in 1944 Hungary, under Nazi occupation. She grapples with the waves of trauma that impacted the mother-daughter relationships — both between her grandmother and mother and between her mother and herself. Literally living their experience in their flesh gives Nadia a better understanding of the scars that shaped her. As in “Life & Beth,” this provides an opportunity to forgive her mother — or at least come to terms with the mother figures she had.

Yet, throughout most of the season, Nadia is determined to do the one thing time travel shows always tell us you can’t do — go back through time and fix her broken childhood, even if it means breaking the continuum of time and space itself.

When her friend Alan chides her for her recklessness, she responds by telling him that “no kid should have to go through what I went through, all right? Trust me, I’ve lived all sides of it.” A similar line shows up in “As They Made Us” when Abigail’s kids jokingly ask her, “you want us to have the same crappy childhood you had?” “Life & Beth” shows rather than tells the extent of that damage.

If we could do it all over again, would we? Is parenting a do-over? “As They Made Us” posits that, in some ways, it is. We see how different Abigail’s relationship with her children is; despite the fact that she feels insecure in her life, they are grounded, happy and honest. The resolution of the movie shows Nathan and Abigail getting their children together. Apparently, building their own healthier, but still flawed, families, is one way they have found to heal.

Still, having a child is not a magical, trauma-erasing solution. In all three of these films and shows, the mothers never change. There is no “coming to God” moment for them in which they are confronted with the pain that they caused their children, no chance for them to show any contrition or empathy.

The only source of real healing has to come from the daughters themselves. For a lot of us, unfortunately, that is a fact of life — whether we’re dealing with the loss of a parent in a way that hasn’t given us closure, or whether our lived experience shows us that the parent we still have will likely not change.

“Just because I came before you doesn’t mean I have all the answers. You’re looking in the wrong place,” Nadia’s mother tells her when she is faced with her somewhere in the time and space continuum. Our answers for dealing with our traumas, at the end of the day, can’t come from our mothers — they have to come from us.

These three protagonists show us a strange roadmap of women doing something brave and difficult — healing their relationships with their mothers. Doing that allows us to be more comfortable in the world and better caregivers — both for our children and, just as importantly, for ourselves.