As far as divorces go, mine was a fairly smooth one. There were no custody fights, and no arguing over who would get the sofa or juicer. The only lawyer involved was the obligatory one who we needed to draw up our fairly simple divorce document. My ex-husband and I remained amicable, and we’ve stood together with our son at each of his seven birthdays since our divorce, singing happy birthday — or, in my case, mouthing the words, as I can’t carry even the most basic of tunes — and helping him blow out his candles.

My current husband and I even had my ex-husband and his family over for Shabbat dinner a few weeks ago. It went really well — I even packed my ex a container of leftover food to take home, as one does!

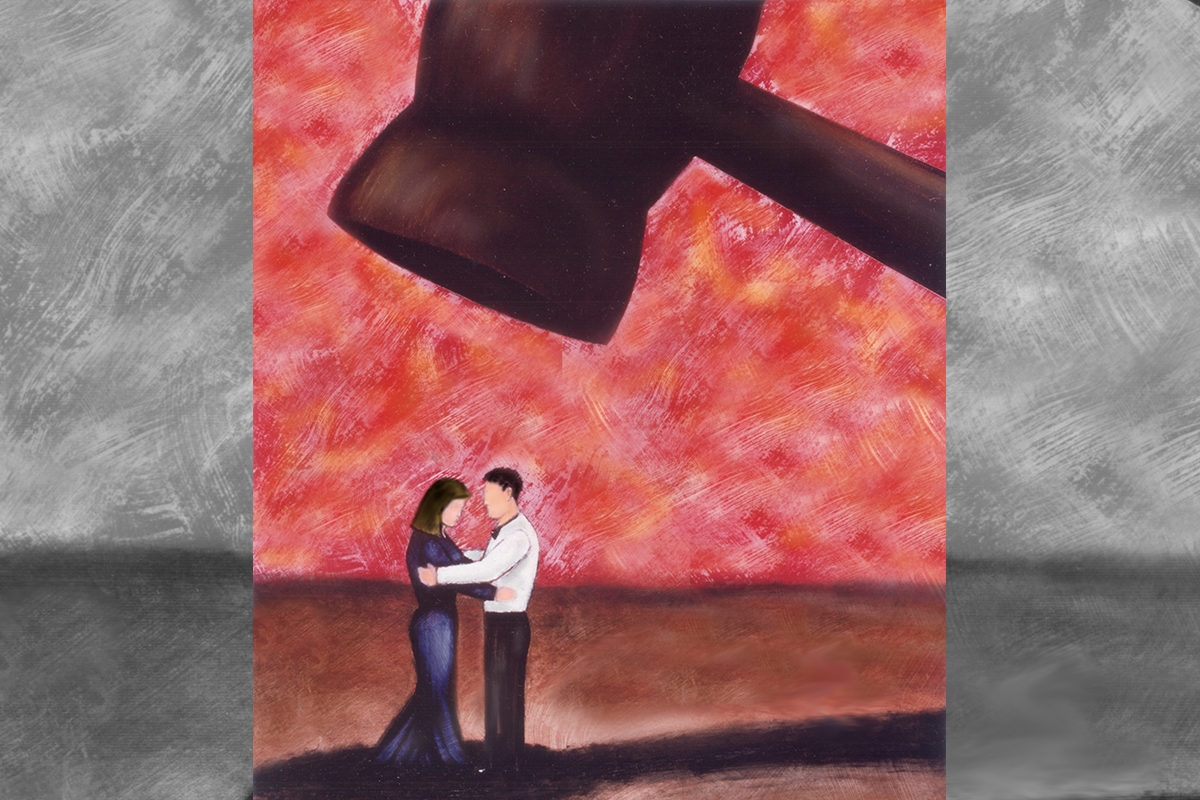

All in all, I feel pretty lucky. But if there was one element of the divorce that went horribly wrong, it was at the Beit Din, the Jewish rabbinical court where we got our religious divorce, known as a get. According to biblical law, a married couple can only be released from the bonds of matrimony through the transmission of a bill of divorce from the husband to the wife. This document, known by its Aramaic name, get, is proof of the termination of the marriage, and allows the husband and wife to remarry others.

The Beit Din in Johannesburg, South Africa, where I live, took our amicable separation, and turned it into a shameful, sexist, and rather traumatic event — for both of us. The experience left me hurt and humiliated, and, as a result, I turned away from Orthodox Judaism, which I had practiced my whole life.

In theory, getting a get is a fairly simple procedure. You simply book a date and time with the Beit Din a few weeks in advance; all you have to do is show up. On the appointed day, the husband arrives and instructs the sofer, the scribe, to write the get on behalf of his wife. The document contains 12 lines of text, written in Aramaic, which basically states the location, the man’s and woman’s Hebrew names, and a short pronouncement that the woman is now free to remarry. Interestingly, the get makes no reference to the reasons why the couple is getting divorced, and also omits details such as child support or custody.

In the presence of the Beit Din, the scribe “accepts” the husband’s instruction. He writes the get; the husband then gives the get to his wife; the Jewish divorce is granted.

It’s worth noting that only the man can declare a marriage over, according to the Torah (Deuteronomy 24:1-2). If he refuses to give her a get, a woman is in “agunah” (chained) and therefore cannot marry in the Orthodox Jewish tradition. Some women might wait for months or years until a get is granted — however, New York, along with Canada, South Africa, and the United Kingdom have passed laws requiring a spouse to cooperate in the religious divorce.

For our get, which we did before our civil divorce, my husband was required to be at the Beit Din three hours before me, as he had to wait until the scribe had finished the document. I arrived at my allocated time and had to enter through a side door — all the men, including my husband, had entered through the main door. My husband and I sat facing each other; the three Beit Din members, meanwhile, sat at a raised platform, much like a judge presides over a court. Two witnesses and the scribe sat among the chairs in the little court.

The get was read aloud — something that reminded me of when our rabbi read our ketubah at our wedding. It was a heartbreaking reminder of our loss and the unravelling of our promises. Then, he and I were told to stand up. I was instructed to walk over to my husband, cup my hands together, and wait for him to drop a piece of paper into my hands, a symbol of accepting the get. I was told to keep my arms low, so I stood there, in the “begging” position. My husband had to declare that he was granting the get of his own free will, and I had to state that I was receiving it that way, too.

I looked up my husband, tears in his eyes, and my cheeks wet with my own. He later told me that he was feeling sad for what I was going through, and I was upset by the humiliation and the literal and figurative position I found myself in.

I then gave the piece of paper to the rabbi, who declared the validity of the get. My husband was told he could leave — but not before everyone shook his hand, and wished him mazel tov. Huh? What were they celebrating, exactly? That my husband was rid of me? That he was free to go and marry someone else the next day? Their congratulations felt misplaced — there was nothing to celebrate that day.

After my husband had exited the main door, I was left with the six men. I was expecting to be told to leave, too, but the rabbi started asking me questions: “Why are you getting a divorce? What did you do to mend things? Do you know you have a child? Have you considered his feelings?”

I wondered what the point of this was — after all, they had already granted my husband the get. Also, why was I made to feel like I was the only culpable one in our marriage? I felt targeted and I felt it was unfair — like the divorce was only my fault.

But also, I was scared — scared of making the rabbi angry, scared of not being perceived as a “good Jewish girl,” scared being in a situation that I had not anticipated, nor could ever have imagined.

After my “trial” was over, I was dismissed with a point of the finger to the side door. I skulked out, and met my husband in the Beit Din office, paying the bill. There were no words between us, just a collective heaviness and sadness.

I didn’t know it at the time, but this was to be my last time in an Orthodox setup.

The get ceremony broke things for me, and I questioned my space in Orthodoxy as a woman. I felt as if my place had been marred. I felt like I’d been purposefully shamed and embarrassed — which is something I had learned, over the course of 12 years at Hebrew school, was a pretty bad thing to do.

While I had long questioned the inequality between men and women in traditional Judaism, it hadn’t bothered me enough to leave. But getting a get pushed me over the edge. It quite loudly spoke of a woman’s space in Orthodoxy — or, more accurately, the lack thereof — and I realized it wasn’t a space I wanted to occupy any more.

With so many changes happening in my life, not going to shul was just another shift to add to the pile. It was remarkably easy to do: Most of my family were living in another city, so I had no strong anchor in the Orthodox community, and there wasn’t anyone around to give me a guilt trip about over not fasting that first Yom Kippur after the divorce.

For about six years after my divorce, I was happy to lightly dabble in Judaism. I wasn’t really following traditions, and I wasn’t missing them. My son was at a Jewish kindergarten — it happened to be a good school close to our home — and so I felt he was at least learning about Judaism.

I got remarried to a non-Jew (at the time), and we had a child. I started missing Judaism — the culture, the connection, the belonging. I felt uncomfortably disconnected, and started feeling guilty that I had turned away from the religion that my great-grandparents had died for, and for which my grandparents abandoned everything. I also felt the need to raise my daughter, along with her older brother, with the same beautiful traditions and faith that I had grown up with. At the same time, and quite unrelated to my desire to return, my husband decided to convert. He had gone to a Jewish day school in the small city where he grew up, and had always felt a connection to the religion.

And so we started looking for a place in which I could reconnect to Judaism and where he could convert. We found a progressive community and shul that checked all the boxes, and instead of sitting on the sidelines, simply observing a service, I became active. And rather than having my voice silenced or overpowered, it became comfortably loud.

A few weeks ago, I read a Torah portion at a Shabbat service, and it was a privilege I never thought I would experience. After the service, this time, it was me getting the handshake from my rabbi, along with a “mazel tov!” And as I walked out of the main door with the rest of the congregation, I realized: This is my place. I’m happy to be here.

Image via Larry Limnidis/Getty Images