Learning a new language in middle age isn’t for the faint of heart. As I commit new Hebrew words to memory, I feel others slip away. I struggle for them and, unbidden out of my brain’s not-English folder, comes a bit of high school French to block my search. Today, on Israel’s 75th anniversary, I think of my grandmother learning Hebrew in her mid-30s.

My grandmother arrived in Israel with two young children in 1948, after the biggest war and into another one — another milhama — as her new country battled with its neighbors. She was stateless and widowed, her husband stolen by the Holocaust. She was turning her back on a Europe that had allowed the unthinkable.

Her children needed Israeli names. My aunt Liliana became another flower — Shoshana is Hebrew for rose. My father, named for his grandfather, shed his German-sounding name. He became Haim, starting his new life with a name that means life.

In Hebrew, immigrants to Israel make Aliyah. Literally they are said to be going up, ascending. But my grandmother left her family and the capital city of Belgrade. She gave up all property rights and surrendered her Yugoslav citizenship. In exchange, she got a neighborhood with open sewers, in a country struggling to provide for tens of thousands of traumatized refugees. What had she descended into, she must have wondered.

At my kitchen table in suburban Boston, my Golden Retriever asleep on my feet, I work through my notes and struggle with my homework. Since 2018, I have tried just about every method of learning Hebrew: a traditional classroom setting at Hebrew College; a three-week Hebrew immersion course at Middlebury Language School; two semesters of an online program called Citizen Café; small group studies; virtual private lessons; a subscription to Izzy for Israeli TV and movies. It’s humbling to grapple with the lyrics of a simple children’s songs or work at puzzling out a comic strip. Oh, to be as conversational as a chatty Israeli 4-year-old!

My father, 10 when he came to Israel, doesn’t remember learning Hebrew. He caught it in school and on the street, swallowing it whole. With the same open fist, he grabbed Bulgarian, so he could talk with his classmates.

But my grandmother must have learned the language deliberately, as I do now. “H’kador gadol,” I repeat after the recording. The ball is big. “H’kador h’gadol.” The big ball. The surprise is, I’m actually finally learning.

As a new immigrant, my grandmother needed a new language. With 90% of Yugoslavia’s small Jewish community murdered, there were few Serbian-speaking refugees in Israel for her to talk with.

My own Hebrew study is voluntary, but it doesn’t feel like a hobby. Understanding and communicating in this longed-for code can feel as satisfying as scratching an itch. It is something so simple small children do it. Yet in my childhood this was always out of reach for me.

My father spoke to me only in English. Six years in the United States when I was born, his focus was on working hard, becoming American. My grandmother had died suddenly in her sleep at 50. If I had got to know her, perhaps she would have taught me Hebrew.

As a child I reasoned since I hadn’t learned already, it was impossible for me to ever speak it. Now as the rain patters on my skylight, I sip mint tea and sit with stacks of flashcards. They help me remember how to ask for a menu, tell time, comment on h’kerech and h’shelig, the ice and snow, here in Massachusetts. After years of listening to hard- to- pick-up Hebrew words my father spoke on the phone to family in Israel or to friends at social gatherings, I’m now learning systematically and it’s working.

On my father’s side, our ancestors spoke Serbian, Hungarian, Yiddish, German, and Ladino. None were native Hebrew speakers. Hebrew was a language reserved for prayer, not everyday life, until the 19th century. Eliezer Ben-Yehuda famously raised the first native-speaking children in centuries by forbidding that they hear any other languages during their early years. Within a generation, Hebrew became the only language that ceased to be a vernacular language and was then revived. Today there are several million native speakers.

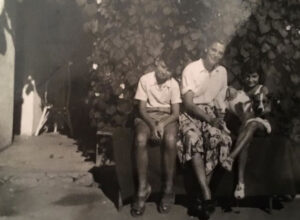

At 52, I’m now older than my grandmother ever got to be. After losing her husband, the love of her life, in the Holocaust, she never remarried, and died of a heart condition in mid-life. I think she died of a broken heart. I wonder about, if this history had been different, if my grandfather had survived, how different our lives would have been. How different my life would have been. If I would have had conversations in Hebrew with her in Israel. The Holocaust stole so much from our family, including what could have been our bond.

Hebrew will never be my mother tongue, but it will always link me to my grandmother and our family history.