I was seven months pregnant when my husband and I moved to Berlin. We were there for work reasons – his, not mine. My main job was to find a gynecologist, pick a hospital to give birth at and rent an apartment suitable for a young couple with a baby. While I worked on figuring out our future, however, Berlin was forcing me to confront my past.

I had been apprehensive about moving there. Having grown up in Ukraine and Russia, I had been taught to resent the German capital for launching World War II. I think the first time I ever heard the word Berlin was in the context of the sentence, “Your grandfather had made it to Berlin.” For a Jewish Ukrainian veteran like my grandfather, “making it to Berlin” meant he was a military hero who’d survived humanity’s worst war and marched on the German capital. But my knowledge of Berlin ended there since Grandpa never talked about the war. It was only after he passed away that I learned why.

Shortly after his death, my grandmother found his confession letter addressed to the KGB that revealed that he hadn’t fought his way to Berlin like we believed. Instead, he’d been captured early in the war and, despite being Jewish, survived four years in Germany through an astonishing series of miracles that brought him to Berlin, where 80,000 Soviet soldiers died in the final battle that ended the Nazi reign of Europe.

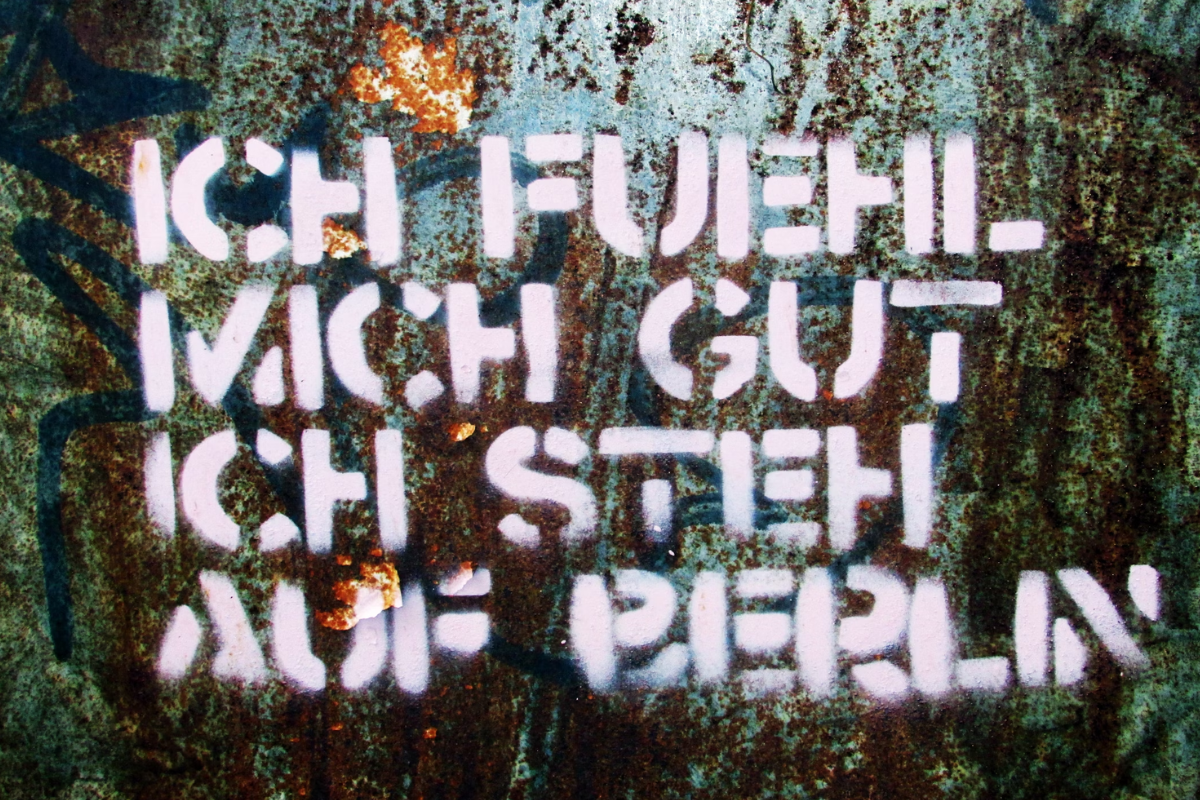

I had expected Berlin to be marked by this dark history, but instead was greeted by a lively city of buzzy galleries, trendy cafes and second-hand clothing shops. Graffiti – mostly of the artistic kind – contrasted with the tony architecture of rebuilt prewar buildings. There were even several Israeli restaurants. The city felt young, international and gritty in a hip way. Other than a few WWII landmarks and museums, it was hard to imagine it as the epicenter of evil. As I was about to give birth there, that felt like a relief.

Yet something strange began to happen as I walked the Berlin streets with my growing belly: I grew obsessed with researching my grandfather’s story. It was as if I felt a sudden urge to understand the price he’d paid for me to exist and be able to carry the next generation of our Jewish lineage in the now peaceful Berlin.

As I threw myself into this work, the city began to respond.

The apartment I found in the family-friendly Prenzlauberg neighborhood was in an old, prewar building sandwiched between a beautiful old cemetery and a big park that housed the hospital where I’d deliver. In preparation for the baby, I scoped out the neighborhood for spots to walk with the stroller. It was then that I first noticed the Stolpersteine (or “stumbling stones”), the sidewalk plaques commemorating the victims of the Nazi regime, many of them with Jewish last names. (When we signed the lease, I also realized why it had been so easy to locate all the German Jews – instead of apartment numbers, Germans use last names displayed above the buzzers right out front of each building.)

The old cemetery across from our apartment building seemed to be popular with other moms in the neighborhood, so one day I went to scope it out. The grand old trees and 19th century graves gave the cemetery the feel of a historic park and it seemed like a quiet shady place to take the baby until I came across a white marble mausoleum pockmarked by shelling. In 70 years, no one had repaired it.

The mausoleum was the first Berlin building I saw that bore the visible marks left by the Soviet army and it was hard not to wonder if my grandfather had risked his life for this very neighborhood. With its echo of death, the mausoleum spooked me. I knew I would not bring my baby to the cemetery.

From then on, my various associated anxieties began to come up in unexpected ways.

As my due date crept closer, for example, I hired an English-speaking doula as a translator because of a paralyzing fear that I wouldn’t be able to communicate with German doctors. It was only later that I realized my fear was based on a memorable scene from a Soviet WWII TV series that I’d seen as a child. In one episode, a pregnant Soviet spy in wartime Berlin gets taken to a hospital where in the midst of feverish labor, she screams out in Russian and gives herself away to the Germans.

It turned out that one of the two doctors who supervised my delivery spoke perfect English and the other spoke Russian. But it was my Jewish doula who told me, once my boy was born, that if I wanted to circumcise him, I couldn’t simply do it at the hospital like in the U.S. In Germany, the only circumcisions were done by Muslims and Jews. Since I wasn’t religious and didn’t want a mohel to do the bris, my doula gave me the name of a Russian Jewish doctor. The procedure took place in a dingy office on the other side of town, on a Sunday. The lights were off, there was no staff other than his assistant and though the procedure went fine, it had an illicit, off-the-books quality to it. Had I been circumcising my son in another European city – say in Rome or Madrid – maybe I wouldn’t have thought twice about it, but this was Berlin and as the cab took me and my baby back home, I felt our acute historic otherness, as if even now we weren’t quite welcome.

As months passed and my son learned to hold his head, then crawl, then start solids, I delved ever deeper into bringing my grandfather’s story to life. By this point, I was writing a book inspired by it. Yet at the same time, I wasn’t doing what a good foreigner should do — that is, learning the local language. Growing up steeped in the national memory of WWII, the German I knew consisted of prisoner marching orders of “Eins, zwei, drei,” “Nein!” – always shouted, never spoken – and “Hände hoch!” or “Hands up!” that I’d seen in Soviet films. After eight months in Berlin, the only additions to my vocabulary were “yes,” “thank you,” “bye” and “my baby.” Normally, I prided myself on picking up new languages. I spoke Russian, English and Italian fluently, and had a decent understanding of Spanish, Polish and French. Yet I felt an aversion to German that was irrational, from the gut. The only explanation was that my research was sinking me deeper into the country’s past.

One day, I took my son to a new playground. At eight months, he was a fast, determined crawler. In the sandbox, a German toddler was playing with a yellow truck and before I knew it, my son had made his way toward the desired object. He must have reached for it when I heard a shriek, “Nein!!!” and found myself running to grab my son, wanting to protect him from a threat that wasn’t really there.

I realize that had I not been thinking so intensely about what it must have taken my grandfather to make it to Berlin as a Jew, I might have abstracted myself more from the past. Yet maybe it’s important not to abstract ourselves. Maybe scars are there to be stared at. Among all those nightclubs and galleries, the Stolpersteine and the pockmarked buildings remind us that it wasn’t always a city of fun and indulgence, that something awful happened here once that should not be forgotten.

Moving to Berlin forced me not to forget my own family’s past. And yet, paradoxically, it was also there that I launched into a new future, as a mother and as an author. Though we no longer live in Berlin, my obsession with my grandfather’s story drove me to write a novel. And now, in a testament to a nation that’s able to confront its history, the German translation of my book will soon appear in Berlin bookshops.