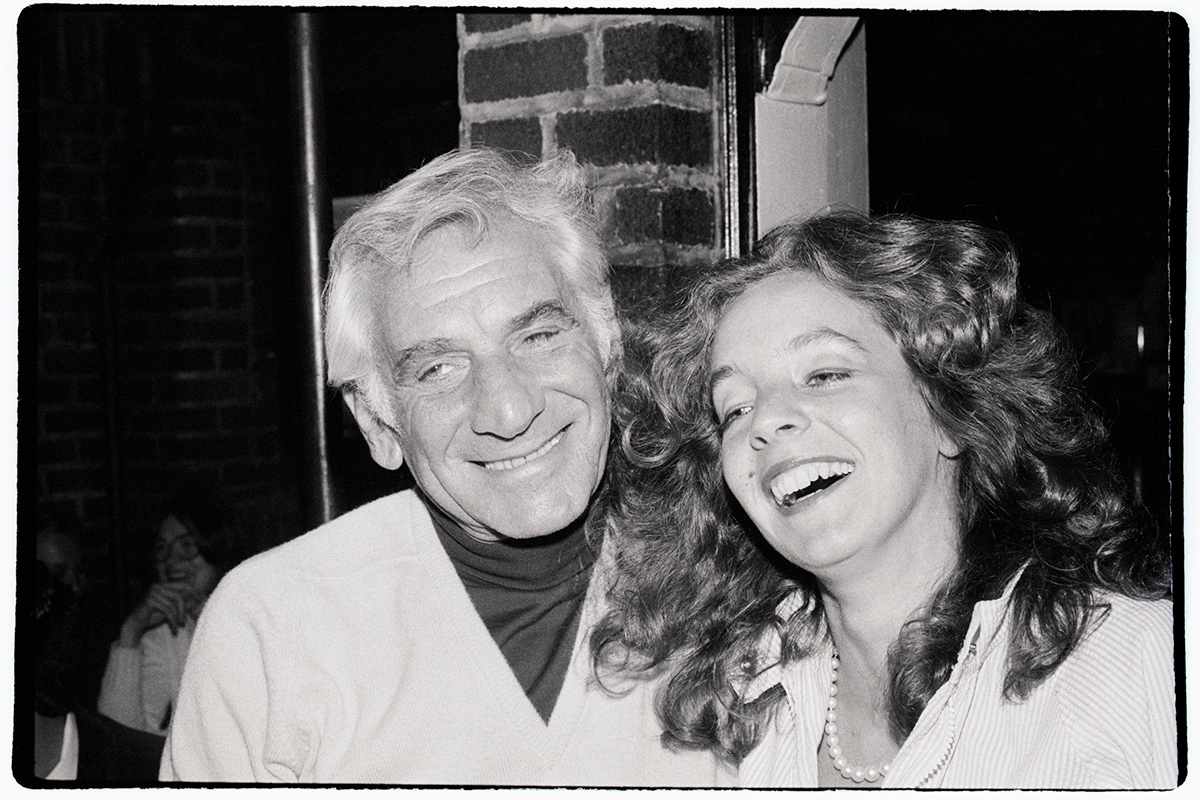

Jamie Bernstein spends every day in what she calls “Leonard Bernstein land.” Her father, the iconic composer Leonard Bernstein, may have passed away over 30 years ago, but his legacy is still as vibrant and alive as ever.

Bernstein is the oldest of his three children, along with Alexander and Nina. As kids, they were raised mostly by their mother, Chilean-American actress and activist Felicia Montealegre, and their beloved Chilean nanny, Julia — as Bernstein recounts in her extremely compelling autobiography, “Famous Father Girl.” And yet today, the three of them are essentially “the caretakers of our dad’s legacy,” she tells Kveller, zooming in from her Manhattan apartment.

That legacy is especially present today due to the recent Steven Spielberg adaptation of “West Side Story,” whose music was composed by her dad. Bernstein loved the movie — “We just thought it was magical… Musically, we just thought it was superb. We didn’t have a complaint in the world.”

Her favorite pieces of her dad’s are “Serenade” and the not oft-played jazz piece “Prelude, Fugue, and Riffs” he originally wrote for Artie Shaw, which ended up being premiered by Jewish “King of Swing” Benny Goodman. She loves the irreverent nature of her father’s music and work: “The whole thing about my dad was that he was a rule-breaker, and a wall-taker-downer,” she says. “His symphonic work is jazzy and his Broadway shows are symphonic.” He didn’t care for rules.

Right now, Bernstein is preparing to narrate a concert of her father’s theatrical oeuvres at the New Jersey Performing Arts Center in Newark — the performance, which was postponed three times (“it’s just been the gig that wouldn’t gig”) due to Covid and weather conditions, will be conducted by jazz pianist Bill Charlap and feature narration and conversation with Bernstein and presenter Ted Chapin on June 17. “It’s all very heimish because we all know each other,” she tells me.

She’s also about to premiere a series of lectures about her father for the classical music streaming app IDAGIO, featuring speakers like Kristin Chenoweth and Bradley Cooper.

Bernstein and her siblings have been in touch with Cooper over the past few years — the “A Star Is Born” director is currently working on a much-anticipated Netflix movie about her father called “Maestro.” “He’s been sending us photographs, you know, over the past couple of years, as he’s gone on his various journeys around this film,” she recounts.

The movie was embroiled in controversy this past week when first images of the movie came out showing Cooper wearing facial prosthetics to look more like the music icon — including a prosthetic nose. Critics have accused Cooper, who is both directing and starring in the film, of “Jewface.” But to Bernstein and her siblings, this isn’t an issue.

“I know that there has been a flap about it,” Bernstein admits, though she says she hasn’t really read any of the articles and reactions. “I think it’s ridiculous. Yeah. You know, he had to make himself look like Leonard Bernstein. And Leonard Bernstein had a big nose and yes, he was Jewish. And what is the problem here? Are we really going to say that they had to hire a Jewish actor to play Leonard Bernstein? I mean, come on, let’s just not get literal-minded about everything in this world.”

Bernstein tells me that earlier iterations of the role had Cooper wearing even heavier facial prosthetics but “it was just too much stuff on his face… he felt that it interfered with his ability to use his face to act. So he cut way back and just let himself look more naturally himself.”

Bernstein thinks the prosthetics are astonishing “and sometimes all the way to spooky. I mean he just looks so much like my dad… The whole thing is eerie and sometimes discombobulating — my brother and sister and I were all in our 60s… And they [Cooper and Carey Mulligan, who plays Felicia in the film] are younger than we are. But they’re playing our parents. So it’s confusing already. We have this… almost parental care about them, but they’re playing our parents.”

Jamie and Leonard at the Piano, Ca. 1950s.

Leonard Bernstein was born in Lawrence, Massachusetts, to Ukrainian Jewish parents — his early exposure to music was on Friday services at his family’s shul. His father Sam owned a successful garment company and was a Talmud scholar by night. “The cherry on top of his whole immigrant success story was going to be to hand over his successful business to his son Leonard to run,” Bernstein says. Sam was not an early supporter of Leonard’s choice to become a musician, as Jamie explains: “In the old country, a musician was a klezmer shabby vagrant with a beat-up fiddle who would slip on foot from shtetl to shtetl, and play at a wedding or a bar mitzvah for a few kopecks and a bowl of gruel.”

“After my father had his Cinderella-like conducting debut and he became famous overnight, some journalist got wind of this story, which is true, that at one point, my grandfather was so desperate to discourage his son that he wouldn’t even pay for his piano lessons,” Jamie recalls. “So the journalist confronted my grandfather: ‘Is it true that you wouldn’t pay for your son’s piano lessons?’ And my grandfather immortally replied, ‘Well, how was I supposed to know he would turn out to be Leonard Bernstein?'”

It is truly an excellent Jewish joke and the type of humor that Sam passed down to his son and grandchildren. Bernstein tells me her book was supposed to have a jokes appendix: “My editor made me cut it… I was so sad. But he said, ‘but it’s an oral tradition. And when you write them down, they’re just not funny enough.'”

Still, at most Q&As about her book, she tells her father’s favorite Jewish joke, which, unfortunately, I would agree, is hard to write down. Trying to capture a good Jewish joke in writing is almost like trying to describe the magic of a Bernstein composition with words — it doesn’t work, you have to listen to it. But I will say, as she reenacts it to me, she takes on a performer’s persona, making all the voices and gestures, channeling the spirit of the cranky Jewish men — and it is a different, but a similar kind of magic.

Another oral tradition her father passed down to her was Yiddish. “I learned a lot of my Yiddish, if not almost all of it from my dad,” Bernstein recounts, “Not all of it, but a lot. Because he and his siblings used a lot of Yiddish.”

“My favorite Yiddish expression is ‘aroysegevorfene gelt,’ which is basically ‘dollar signs flying out the window,’ so you say it when you’re really wasting your dollars. It’s fabulous, right? But there are so many. It’s just such a yummy, chewy language, you know, and it has so much humor in it.”

Another one of her dad’s favorites was “dem roshe helft azoy muser zogn vi a toytn bankes,” which means “it would help like cupping a corpse.”

Bernstein tells me about their seder gefilte fish controversy (she is on team gefilte, other members of the Berstein family decidedly are not), the fact that their Chilean nanny made the best matzah ball soup, and about how their father’s love for a good corned beef and pastrami sandwich was passed down to her eldest daughter, Frankie.

The Bernsteins may have been culturally very Jewish, but their relationship to the traditional, spiritual aspects of the religion was more complicated. In her book, Jamie describes their relationship with Judaism as nebulous; she recounts her mother’s disdain for her paternal grandparents’ old country Jewish ways. Her brother had his bar mitzvah, and on Yom Kippur, he and her father would go “shul hopping” — Jamie once joined them on a shul-hopping excursion, but when she was asked to sit in the women’s section, she decided she was out. The biggest event in their family was the Passover seder — “we’re still using our grandfather Sam’s dog-eared old-fashioned haggadot. And they are wine-stained and ripped up. And they’re a mess, but we use them.”

Yet Bernstein doesn’t close her mind to the idea that God could exist. She describes herself as agnostic, and when I ask if her father was the same, she struggled to answer. “His own spirituality was very complicated,” she says.

“You can track his lifelong struggle with his spirituality and his lifelong argument with his spiritual maker through his musical compositions all the way through his life. So many of his pieces engage in a kind of fist-shaking at the heavens. You know, if you’re up there taking care of us, why is everything such a mess down here? And why are we also horrible to each other? And what are you gonna do about it? And, you know, who’s minding the store anyway? Of course, this is a very Talmudic thing to do, to argue with God.”

Yet her father did find spiritual purpose in one place: “He went back and forth a lot between being optimistic and feeling like humankind was getting better, and then getting very pessimistic and feeling like we weren’t getting anywhere… the act that made him feel like it was possible to go forward was, in fact, the act of making music. That’s what made him feel like he could go on.”

Lately, Bernstein has been showing up in a lot of lists of famous Ukrainian Americans and Ukrainian Jews. “The irony is that both of his parents had to escape from Ukraine because of the pogroms,” Bernstein says. “So I’m guessing that they were ambivalent in their nostalgia for the old mother country. But all the same, you wouldn’t want to see it torn up and have even more people being killed. So that’s totally horrible.”

One thing is clear to Jamie: Leonard Bernstein — the known activist, the man who stood against the Vietnam War and nuclear armament, who raised money for AIDS research and fought for civil rights; the man who, towards the end of his life, conducted a symphony as the Berlin Wall came down — would have a hard time witnessing the state of the world, the war in Ukraine, the Trump presidency, the stripping away of reproductive rights, the anti-gay legislation rearing its head.

“He was such an advocate, such an outspoken activist that, you know, he would just be out there shouting in the streets, and doing everything that he could do and putting together concerts and protest and events,” Jamie says.

Still, she thinks he would’ve loved to discover that he was a queer icon — after her mother’s death, she recalls, her father “tried to be out, but he couldn’t quite sustain it.”

“One of the reasons was that his mother was still alive — you know, Jenny Resnick from Ukraine shtetls, still living in this very Jewish conservative neighborhood in Lawrence, Massachusetts.” Jamie says he couldn’t find a way to come out to her, and Jenny ended up outliving him.

Leonard Bernstein was not a particularly involved dad, at least not in the way we would want a dad to be involved in the child-rearing in these modern days. But hearing Jamie speak about his, it’s clear that he was an excellent father to his children, in his own way.

“The thing about my dad that was really great is that he loved being around us,” she professes. “He loved spending time with us — and, of course, teaching us stuff because he could never turn off the teacher faucet ever. And for us, it was more like a teacher fire hose. You never stopped, but it was all part of the fun, you know, and he loved taking us to see things, to music and movies and theater. He would play things for us at the piano… His own childlike enthusiasm was a great thing to share with his own kids.”

“That’s really the most precious thing I cling to in my memories of him: just how much he enjoyed sharing life with us.”