Ten years ago, I sat in synagogue for the only hour I agreed to attend a year. I was a few months pregnant, listening to the women around me discussing a nice young doctor on the bimah and his marriage potential for their daughters. Bored, I idly wondered if I would find myself there too in the future, pondering the matrimonial prospects of some poor, unsuspecting young man for my child. I followed the prayers, and the clock. Like most Jews I fleetingly considered my own mortality through the parable of the Book of Life but at 33, the chances of death seemed remote enough to not really consider. Even more so, with a small human growing inside me, new life was the focus.

The Book of Life was being written, though, and unbeknownst to me or my husband, a name was not going to make it in. It was the name of our unborn child, Shoshana, for whom death was going to take before she got a chance at life. Death, in the form of stillbirth, two days before her due date.

For many, God brings calm and hope when there is death, even an explanation. As a profound atheist since the age of 16, when Shoshana died, I was left devoid of these things, at sea with my grief and completely destroyed by it. I cannot say that my husband, a believer, fared much better, but he had some rituals and understanding that brought him an edge of comfort, a vague pathway even if it was not one he expected to walk down.

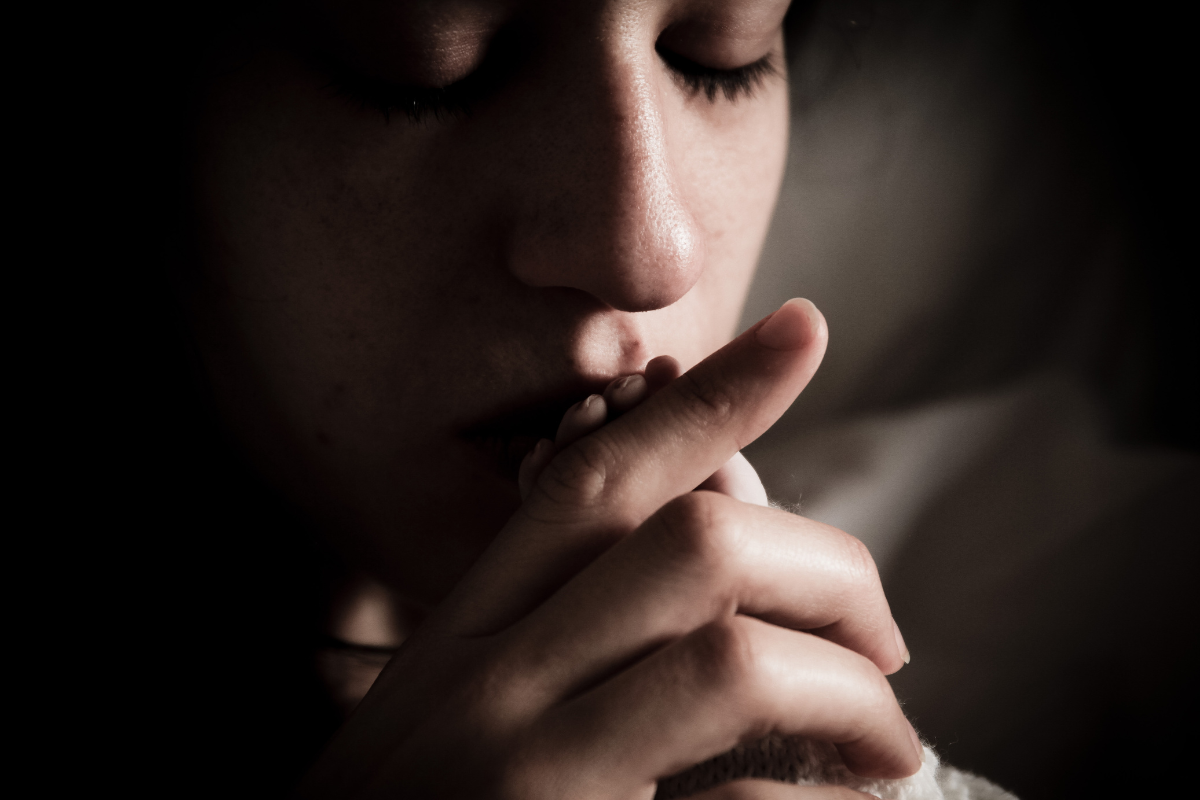

When a small, lifeless but desperately loved body was handed to me after birth, I felt totally powerless. It felt like I had failed in all aspects of motherhood, with nothing to give our daughter. No comfort, no food, nothing, just silence and death. So, I said Kaddish. I never thought I would turn to religion for anything, yet it was the only thing I could think of to give her in that moment. My husband whispered the Hebrew words he had memorized over the years at countless shivas, which were now being quietly repeated to his daughter. I offered maybe not a hope of an afterlife, which I still do not believe in, but the strength of prayers uttered for generations, which have connected our people for centuries.

As word spread of our loss throughout the community, many people fell into platitudes. They wished us a long life, while I pondered the incredible idiocy of that statement. I did not want a long life; I wanted a short one. I wanted to be with my child, not trapped here away from her. But after hearing it a number of times, its meaning, or intention, started to shift. Yes, it can mean that the comforter does not wish you to bear the same mantle as the deceased, but it’s also a hope for a life that allows you to tell their story.

All our narratives are told by those who get to live on after us. I gave Shoshana a life through mine, and in due course, when my husband and I had two other children, we told Shoshana’s story to them. We are bringing her a long life by wishing it for ourselves.

And beyond platitudes, our community showed us the power of collectiveness that exists in Judaism. They organized a meal train without which I think we might have starved. Jewish love comes from food, but in doing so, it brings a level of innately practical support and care: I thought about you, I made this and I am here for you in it.

The more formal aspects of Judaism have brought their own points of positivity and pain. Our daughter died on Erev Purim. It is a dark day festival for us now, and I cannot imagine a time when my living children will get the joy of dressing up and celebrating it. In a miserable irony of timing, this is then followed by Passover, a holiday whose story includes the death of the firstborn. It remains my most hated holiday. As a practicing, if non-believing, Jew, I know I must celebrate it, but almost a decade on from Shoshana’s death, it still cuts me through.

We go to Yizkor each year, a service I never expected to be at until my parents passed away. I attend and wonder at the quantity of pain I feel in that moment. I feel too young to have lived this much hurt. I position myself against a wall and use it to prop me up, unable to stand fully under the weight of grief. I loathe it each year and yet I attend “religiously,” for those moments of connection, an opportunity provided by the synagogue to pause my busy life and sit with her in the stillness of hers. I cannot imagine, outside of religion, another opportunity to be able to do this.

At home we have brought connection through Judaism, too. On Shabbat, when we light candles, we always light three, the extra one being for Shoshana. It’s a visual reminder each week for us and our living children that she remains a central light-filled and guiding source for our family.

And while we were always clear that our two living children were never replacements to Shoshana, we wanted a connection between the children. We gave them both the Hebrew middle name of Keshet, meaning “rainbow,” a “rainbow baby” being the moniker given to a child born after a loss. I smile each time they happily draw rainbows or when my living daughter comes downstairs dressed, once again, looking like every color exploded on her clothes.

My obstetrician, who it turned out was a religious Christian on his own pathway to atheism, ended up in a conversation about God with me on my last follow-up appointment.

“If you don’t believe in God,” he asked, “then where does your hope come from?”

My response was simple. “People,” I said, because what I learned the most about my religion after Shoshana’s death was the incredible power of community. It was all the people, Jewish, Muslim, Christian and atheist, who came together and held us up when we could not stand for ourselves.

As a religion, community sits within the center of our faith and it is this that I held onto so tightly and I still do. It is why I now host large holiday meals and ensure no one is left with nowhere to go. It is why I try to put as much joy as possible into them, because there will always be an empty seat. The death of the firstborn at seder will always put a knife through me, but with community at my side, life continues, and so does hope and happiness.