Matisyahu was part of my formative years in a way that’s become etched in my body forever. As a young soldier in Israel, 18 and 19, I’d have to serve on kitchen duty regularly, and the person in charge of the speakers had only four songs to play, which included one by Matisyahu and not one but two different versions of Toto’s “Africa.” Whenever the latter played, I gritted my teeth, counting the seconds until I could move my body and scrub tables to the infectious beat of “King Without a Crown,” hoping the 2004 hit from the then-Haredi singer could help me finish my tasks before the 1982 song about blessing the rains down in Africa came on again. I was raised a secular Jew, and yet somehow, Matisyahu’s chanting about Hashem to those infectious beats was a comfort.

Over a decade later, I still can’t listen to the song “Africa” without recoiling, and I still start dancing the moment I hear the Matisyahu song.

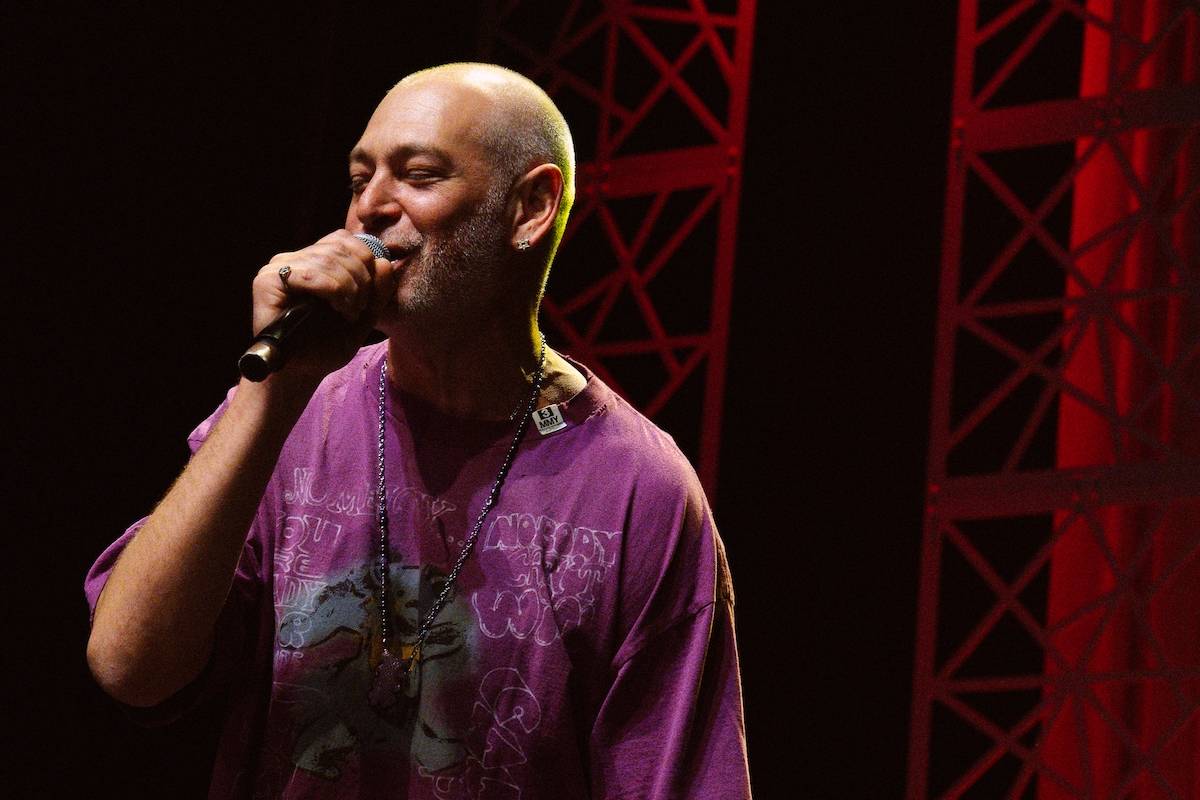

This month, Matisyahu became part of what I don’t doubt will be many Jewish college students’ formative memories, too. At the same age that I learned the power that his music holds to get you through the most menial tasks, students in Philadelphia, New York and Boston hopefully learned about the power Jewish music has to buoy us through tough times at a series of concerts organized by Hillel International called Yallapalooza. At each show, Matisyahu performed with some of Israel’s most iconic artists, including Eurovision winner Netta and pop sensation Noa Kirel.

Throughout his decades-long career, Matisyahu has gone through many transformations. We first came to know the man born Matthew Paul Miller to a Jewish family in New York as a Hasidic reggae star, with those dark side curls and heavy garb, singing about wanting “Moshiach now,” and a day in which there will be no more wars — and also giving us the rare Hanukkah banger, “Miracle.” Eventually, he stopped identifying as Hasidic and presented instead as a surfer-like, silver-locked wanderer, inconspicuously joining street musicians while they performed his tunes. Most recently, he put out songs about antisemitism and being “Fireproof” in what has been for many Jews their toughest year yet.

Matisyahu may no longer be Hasidic, but this year, his connection to his Jewish identity has been perhaps more powerful than it has ever been. After October 7, he’s traveled to Israel, where his oldest son Laivy lives and makes music, on multiple occasions, even shooting a video for his song “Ascent,” a reflection on the nature of antisemitism, at the sites of the Hamas attack. Stateside, three of his concerts were canceled because venues claimed they couldn’t provide the security needed to protect their concerts from protesters.

When I talk to Matisyahu over Zoom earlier this month, there’s a pure, open energy to him, the same one that’s evident in all his music, in which he talks openly about struggles with addiction and his relationship to Judaism. “I kind of think that music is a sacred thing,” a then-Hasidic Matisyahu once told NPR, and that seems to have held true for him through his entire musical career, no matter the changes and upheavals. When we speak, he’s just come back from his kids’ Halloween parade and sits in his yard at home, smoking, as he talks about music and parenting and being Jewish right now.

How was your kids’ Halloween parade? What did you dress up as?

I got hand-me-downs from my younger sister, “Paw Patrol.” So I had the costume on as I was driving to school, and my daughter, who’s 4.5, wanted to go faster. And I’m like, “No, I don’t want to get stopped by the police officer.” She goes, “But Daddy, you’re a police officer!” But I don’t really watch that show.

Me neither. I love “Bluey.”

I love “Bluey,” I love “Fraggle Rock.”

Gosh, “Bluey” is so good.

I remember when I discovered “Bluey.” I’ll never forget the night because one of the kids wouldn’t fall asleep and I was just searching on the TV, and I found it and they fell back asleep within five minutes, and I ended up binge-watching five seasons until sunrise.

I was recently watching an old video of you in “Shalom Sesame” beat-boxing with Moishe Oofnik — that’s Oscar the Grouch’s Israeli cousin, for those not in the know. It’s so great.

I was showing that to my little kids recently. I remember exactly that day and that moment of filming it in Jerusalem. It was awesome.

What are some things that you were looking forward to with these Yallapalooza concerts?

The shows are going to be incredible. It’s going to be so nice to come together. I’m going to have my band there, most of whom I met in college at the New School when I started doing music. The people you meet in college may end up being with you for most of your life and that was my case.

So you’re going full circle with your college friends at a concert for college students, creating those core memories.

We’re creating spaces that are conducive to people to have those experiences, that will create those memories.

I don’t know how I would have handled being a college student right now. I would have felt really isolated, really angry. So at the very least, I feel like it’s nice to be able to show up for the shows and be a help in some way.

You’re performing with some really amazing Israeli acts. Are you a fan?

Well, I know Netta because we did a performance together in Israel. She came out during my set and we did “Sunshine.” It was so cool. She’s so talented. I like to beatbox, and I recently started looping my beatbox. She’s a master at that, and she’s got an incredible voice. She’s a great performer, a powerful presence, and that’s what we need right now.

Noa [Kirel], I met her once, but I know that everybody loves her. And Yonatan [Cohen], I met him in in Israel when I was there at the hospital. He’s a survivor of the Nova Festival and I also had him in my video and perform with me. He’s a total sweetheart, and his music is really, really spiritual and really powerful. So I think it’s a really great line-up.

Do you have any favorite Israeli musicians that you take inspiration from for your own music?

Well, my favorite Israeli musician of all time is Yosef Karduner. I just remember when I was becoming religious, there wasn’t a lot of music I could listen to. He’s the one who wrote the melody to “Shir La’Maalot.” I love him. There’s so many new artists, Israeli artists. My son Laivy is in Israel right now, he’s 19 and he’s an artist, and he’s working with these producers, Doli & Penn, they’re great. There’s so much good music. My wife has an Israeli playlist that she listens to when she drops the kids off at school. The kids love it. It just feels good to listen to Hebrew, anything Jewish right now is so inspiring.

You’re someone who’s gone through so many shifts in your relationship to Judaism, publicly and not publicly. How has this year changed that relationship?

Being Jewish was always at the forefront and the center of my career, or at least a solid portion of my life, from the age of 20 to 35 or so. And I wasn’t raised that way. It was a choice that I made. It was a feeling that I had when I was in college. I was feeling very isolated, and I wanted to connect to something Jewish. I was questioning my identity and all these things, and I went on this journey. I ended up in Chabad. And then over time, I started to feel like it was less important to me. I had dedicated a big portion of my life to Judaism and self-discovery through Judaism. And at some point I felt like I wanted to be just kind of relaxed. Like it wasn’t my obsession anymore. It wasn’t my main focus. I wasn’t doing things anymore because of the rules that “I have to do this or else this will happen.”

At some point I just started being like: I want to go back to being Matt Miller and figure out the simple things in life, like being a good father, being a good husband, what are the things I like to do. Not everything has to have layers of meaning, or has to be searching for these incredible deep experiences or spiritual moments. Having those moments personally from time to time, but not chasing them, and not obsessing about God and being Jewish, I found that it became less at the forefront for me. It became just a part of my identity, and not the entire thing.

Then after October 7, I just felt like there’s some kind of shift, because for me, it’s not about religion anymore. Before, it was about, are you religious? Are you not religious? And that was the deciding factor as to what type of life you live, and how Jewish of a life you have. And after [October 7], it’s no longer about religion. Some people have this very, very deep sense of being Jewish, and some people don’t, and the ones that do after October 7 — there’s a shift from whenever your awakening was. Mine was literally the morning of [October 7]. My son was in Israel, and I was playing a reggae festival, and I just felt out of place. And then I saw someone with an Israeli flag in the audience, and I pulled them up on stage just out of instinct. I immediately went back to even pre-Matisyahu, when I was performing at open mic clubs in Bend, Oregon. I would ask the audience who was Jewish, and I would have an Israeli flag, and I would bring people on stage to hold the Israeli flag while I performed. That was before I became religious or modest. That Jewishness and that connection to Israel, it was there for me before everything, before I knew anything about the religion. And then it returned after October 7.

Nowadays, [my Jewish identity] is again at the forefront, in a different way than it used to be for me when I was religious. But it’s back at the core, the forefront, the obsession again. Very, very organically, unfortunately, because of negative events and because of discrimination, because of antisemitism, because of the pain of the hostages and the hostages’ families and Israel and what all that means. So not so much like a choice, like “I really want to dedicate myself to God or explore Judaism or put a bunch of rules around myself,” but more like, “This is what it is, this is who I am, who we are.” It’s a feeling of real connection now to other Jews. Jews drive me crazy, and we drive each other crazy. But when something like what’s happening right now, which I don’t think has happened for any of us since we’ve been alive, is going on — you drop all that stuff, and you start to appreciate all these little weird things and annoying Jews. You really feel that they’re your family.

I so relate to that. As someone who grew up secular Israeli and wasn’t thinking about my Jewish identity, when I moved to the U.S. it started feeling like it was such an important part of me. And especially this year. You’ve been to Israel, you’ve met with people so impacted by October 7. What were those encounters like?

Well, being at the site of the Nova and being at the kibbutzim, was really life-changing. Standing on the site of the Nova Festival, imagining myself at a music festival and that happening, that was powerful for me.

That’s your world, you spend so much of your life in similar places…

Exactly. And it’s always been a deep fear of mine, to be on psychedelics and something really bad happens, and this is the worst thing that you could ever imagine. I don’t know how anybody recovers after that.

I would say that the deep connection between Israel and Israelis and American Jews, or Jews of the diaspora, is so potent right now, and you can really feel it. But there’s a cultural barrier oftentimes. Even being Matisyahu, going and playing music in Israel in my early days, Israelis were kind of excited that there was a Hasidic Jew, someone representing Jewishness, but I’m not someone necessarily representing them as Israelis. And so my music over there has always been like… I don’t know that people would really understand my music when I would play live shows.

But then I had this moment where the BDS protested me in Spain and threw me off a festival, and it became a big to-do, and I got invited to Israel right after that. I played a show outside of Auschwitz, and I did a little tour through Poland. It was a really powerful time. And this was 10 years ago. After that in Israel, I felt this different connection. People felt like, wow, OK, this happened to an American Jew. He got protested, he got canceled, for being Jewish, for being pro-Israel, essentially. And so I felt a deeper connection with people in Israel after that moment.

Now you feel that again. You know, obviously there’s only so many people that speak up or feel strongly about Israel. So I think Israelis really appreciate it.

Has your relationship changed to any of your own songs since October 7?

It has. A lot of my lyrics are metaphors about spiritual or inner stuff. If I want to say something about the hostages or about antisemitism or whatever it is, what I’ve learned over the years is that my music and the lyrics speak for themselves. Rather than stopping the music to make a speech, it’s way more powerful if you can figure out how to make that speech through your own music. So I just say the lyrics with maybe a slightly different kavana, a slightly different intention, and all of a sudden the lyrics are showing to me multiple meanings. How they are fluid, like water. For example, if I was singing “Lord Raise Me Up” at a time when I was dealing with addiction issues, obviously I was thinking in that context, right? But after October 7, I’m thinking of, literally, the hostages in the tunnels in Gaza, like raising me up from the ground. We’ve been here too long. So the words in some ways went from this metaphysical kind of fight to an actual literal meaning for a lot of them.

It’s poignant, how this past version of you wrote words that so perfectly meet this moment.

If something is written in a pure way, like the Torah, it is constantly changing. It’s fluid. You’re constantly seeing new things in it. And I think that lyrics and poetry, music, art can be like that as well.

Are you working on any new music right now?

I have about 25 songs I recorded pre-October 7. I released some of them on this EP called “Hold the Fire” back in February. But I’m going to be releasing all this new music. Right now, I’m trying to figure out the best way to do it, because I’m managing myself. I’ve been dealing with more of the business of Matisyahu and trying to understand how the record industry works so I can be independent and don’t have to give up large portions of my percentages. It’s a do-it-yourself world right now in the music industry and so the more you know, the more you can do it yourself. But as an artist and a father, juggling all of those things can be tricky. But hopefully I’ll have a new song out soon.

What are some things giving you Jewish joy in this moment?

Israeli music is one of them. Jewish holidays and reconnecting to them. I had a sukkah this year. I called a friend, I tell them, like four hours before Sukkos, “I think I want to have a sukkah.” Next thing I know someone is building a sukkah on my deck. They drop off a massive etrog. There’s a lot of love, a lot of support and Jewish connection.

And then seeing people now, like Michael Solomon, Michael Rappaport, Brett Gellman, Montana Tucker. There’s this kind of community happening that I don’t think I ever felt before. Organic things are popping up from groups like Betar to people like Franky of “Nice Jewish,” who are doing Jewish events because they feel this connection to being Jewish right now.

When all this crazy shit is going on, it has to get balanced out with a certain amount of light. It’s our responsibility. We have no choice but to be the producers of that light right now. It’s what Jews are meant to do as the chosen people, the people of the book, the originators of one God and all that: We have to lean in.

We’re kind of squeezed… It’s not a nice metaphor. But the metaphor is, like, you know the incense in the Temple, when something is crushed and broken, that’s when this beauty comes out of it. So you’re gonna see all of this beauty and light blossoming out of the Jewish people right now in many different ways. It’s easy to get held down, but beyond social media and the news and all the bad stuff that’s going on, there’s a lot of great stuff happening.