If there is one scene from Hulu’s “Fleishman Is In Trouble” that will stay with me for eternity, it is Claire Danes’ scream from episode nine, “Me-Time.”

In the episode, Danes’ character, Rachel Fleishman, finds herself at a new-agey yoga retreat with her lover — married man and pharma mogul Sam Rothberg. When none of the massages and exercise classes seem to assuage the progression of what we will later find out is her imminent breakdown, a massage therapist sends her to a “scream room” where she is urged to release some of her anger. Her first scream there is shy, polite, inhibited. But then the dam breaks. Prodded further, Rachel gives a visceral, unending roar. In a cartoon, it would have shattered windows.

Watching it, I, too, wanted to scream.

“In hardship shall you bear children” is the curse Eve receives for daring to eat the apple in the Garden of Eden. And in hardship many people do bear children. But hardly ever has a television show explored the emotional viscera of that hardship quite like “Fleishman.”

Earlier in that same episode, we get to see the birth of Rachel’s first child — her daughter Hannah — from Rachel’s perspective. Her then-husband Toby (Jesse Eisenberg) isn’t there to see a doctor break Rachel’s water without her consent, a violation that ultimately ends with an emergency c-section. It was that moment Libby (Lizzy Kaplan), who narrates the show, says turned Rachel’s life — with an exciting career and a husband she loved — from great to not great.

“There she was paralyzed, literally paralyzed, splayed out like she’d been crucified,” Libby narrates. “Any power she ever thought she had was suddenly gone.”

It was, Libby says, the worst day of her life.

Watching this, I was immediately harkened back to my own deliveries, which I consider the best — and also the worst — days of my life. During the birth of my second son, I cried so hard while on the operating table they had to pause the operation.

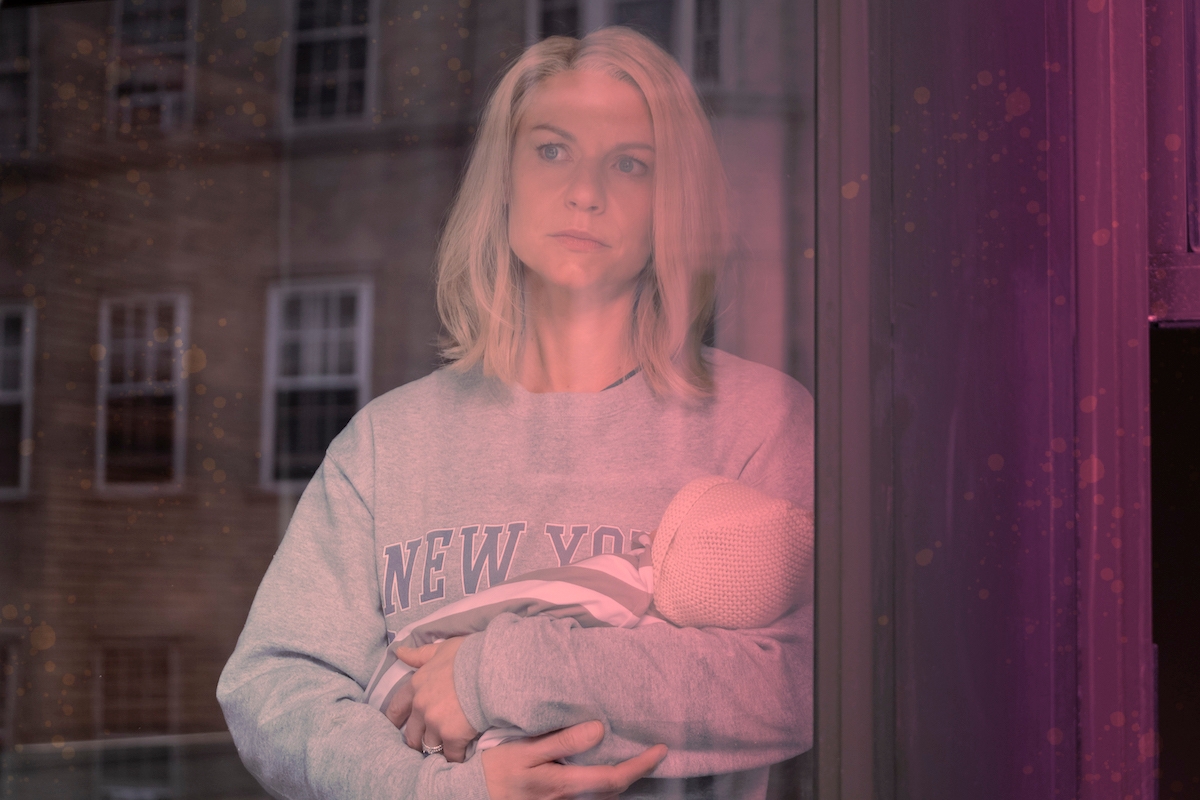

Rachel’s experience in “Fleishman” is super specific — but also so deeply, painfully relatable to so many of us who have given birth in less than ideal circumstances. In the days after that soul-tearing delivery, Rachel struggles to connect with her newborn, and to life in general.

“I feel like I’m in the wrong gear or something,” she tells Toby in the dark days after Hannah’s birth. Instead of going to a support group for postpartum anxiety and depression, she goes to one for survivors of sexual assault. She feels — and rightfully so — that her body had been desecrated in a way that she had no control over. It’s there that she finally finds a way to cry among a group of supportive strangers.

Traumatic birth, postpartum depression, the grief and the loss that comes with being a mother — all these things aren’t just singular moments in time, and they aren’t confined to the weeks, months or even the first year after bearing a baby. Jewish tradition tells us to be fruitful and multiply, but what a price it is we pay to fulfill that commandment.

Motherhood is a chasm. Sometimes, the chasm starts with a crack, like the moment you get pregnant; sometimes it opens wide and violently all-consuming with birth; sometimes it slowly widens and widens and you don’t realize the magnitude of it until years after you give birth, when you look around and notice all the subtle and extremely non-subtle ways it has forever changed your career, your relationships, your life.

Just like Rachel Fleishman, I felt out of control when I gave birth to my sons. Nothing went the way that I planned, and despite having a loving husband, one who is supportive and shares so much of the responsibilities of our household, I felt so, so alone. And angry, too. Angry that there would never be space for me to process what happened. Angry that my one partner in all this could never truly understand what I went through. Angry at the betrayal of medicine and my body.

One thing I did have that Rachel didn’t was a Jewish mother I could turn to. Her labors were nothing like mine, and yet she knew, instinctively, how to help me with my mangled body. In those days after giving birth to my son, she took care of me like a child — helping me shower, dress my wounds, and merely move around — all the while walking me through the first baby steps of motherhood like nursing, bathing, cleaning, massaging and singing to my little one.

In “Fleishman,” there is no one to help Rachel. Toby’s mother, towards whom he harbors some resentment, is not there, and Rachel’s own mother passed away when she was a child. And so the things that people say are instinctual about parenthood, but are often taught in subtle ways beyond your baby birthing and childcare classes — the music of it, the tenderness of it — do not come naturally to Rachel. How should you know to smile at a child when you are shipwrecked? How do you give a child security when no one ever gave you that? Rachel hates herself for her inability to know what her baby needs beyond the physical.

Meanwhile, fatherhood does come more naturally to Toby. Despite his many faults, he is an incredible father, something which makes Rachel feel even more isolated. To him, she is missing out, but to her, she is trying to put on an ill-fitting suit. Toby never acknowledges that fatherhood hasn’t changed his body, or in any real way, his career — he keeps working at the hospital, unaware that Rachel is completely falling apart. Toby wants Rachel to take care of herself so that he could have her back. The thing he doesn’t know is that the Rachel he knew before giving birth will never be back.

The truth is, motherhood forever changed Rachel’s life long before she gives birth. She knows, even before she gets pregnant, how her skeevy male boss thinks having children will arrest her career. She knows that she will keep getting passed up for promotions with pathetic excuses. She knows that the only way for her to have a fulfilling, freeing career is to start her own firm.

When Rachel decides to end her maternity leave by leaving her firm, for Toby, it’s just a power-hungry move, a way for her to come back on top and “monetize the whole system.” But for Rachel, it’s literally her only viable lifeline, taking control of the only place where she feels like a person again.

In doing that, Rachel is taking care of her own family. There’s a reason why she calls her firm Fleishman — subsuming even her greatest achievement in Toby’s name, in the name of her children. Rachel takes on everything that she can — the mental load of making sure that she primes her kids for the kind of life she thinks they deserve, getting them into the best schools, the best camps, the best connections. But she still feels alone.

Libby’s birth experiences aren’t shown in the series, but the way motherhood forever changes her life is also clear. When we meet her, she’s in the New Jersey suburbs, a stay-at-home mom who’s given up a career as a journalist, the one thing that made her hungry for life. She’s surviving, but not necessarily thriving. And while her husband Adam (Josh Radnor) is amazing, he doesn’t quite see how and why she flounders.

That’s why she latches onto Toby’s story, as flawed and one-sided as it is. It is the one thing in a long time that makes her feel something beyond the monotony of her day-to-day life.

“You secure your own oxygen mask before you secure the children’s,” a doctor tells Rachel. It’s a metaphor Toby later resents when he feels that Rachel has taken too much time to, well, completely fall apart, angrily retorting that it’s just because grown-ups need more oxygen than kids and it’s not meant to be some grand metaphor for life. But Toby, I disagree — we’re putting on our oxygen because it’s the most basic thing we need to survive as mothers so that we can then take care of our kids. We no longer take care of ourselves for ourselves. We do it for them.

There is so much irony in “Me-Time,” both the episode and the concept in general. Because what exactly is “me-time” when you’re a mom? Can you extract yourself from motherhood like a velcro strip? There is no way to temporarily excise the physical and emotional toll of it all; it’s embedded and messy like a c-section scar. For Rachel, in what is arguably the best episode of the show, taking “me-time” means literally having a weeks-long breakdown where she loses all concept of time and reality. As someone with so much privilege — a private school education, a beautiful home on the Upper East Side, her own firm where she’s the boss — she shows us what happens when those postpartum wounds are left to fester.

In the “Fleishman Is In Trouble” finale, Toby says the customary Jewish blessing for children over his daughter, Hannah, who has just decided she will not have a bat mitzvah because she wants to break tradition and forge her own path.

“May you be like Sarah, Rebecca, Rachel and Leah,” he recites in Hebrew and then in English, eyes closed with reverence and emotion, cradling the head of his beloved daughter. And it is a blessing, but it’s also a curse. The matriarchs, including Rachel of the bible, knew the sorrows of bearing children.

So what does that mean for Hannah’s future? How do you break a tradition of such insurmountable pain? How do you break a curse as old as the book of our people? Certainly, you can choose not have children, a valid option so many more of us talk about nowadays. But for those of us who — like Rachel, like Libby — want to have kids while holding onto some semblance of the lives we’ve already built and love, how do we answer that question?

“Fleishman” doesn’t offer any easily-wrapped-in-a-bow answers, just like life. But maybe the answer — the same as the source of the curse — is knowledge. Maybe we must share these experiences, and share this pain, not so that those around us can completely understand it or take it away, but can help carry its load.

As for me, I don’t know. Some days, my own two labors — a word that I am so tempted to put air quotes around even though I know a c-section is a legitimate way to give birth — still feel like open wounds. I wonder when I will finally be over this. And I still ask why did this happen to me in this way? Too often I think about all the things I should’ve done to maybe, possibly have a different outcome, as if there could’ve ever been a guarantee, as if I wasn’t working in a broken system, as if it really would’ve made me a better or happier person to give birth in a different way (I don’t know! I can’t know).

What I do know is that watching “Fleishman Is In Trouble” gave me a measure of solace. Seeing my experience, dizzying on an OR table, in a character as nuanced and complex and ultimately quite lovely as Rachel, felt like a balm. Watching someone cry the way I cried so often made me feel understood. And knowing that this experience exists for all to see in a TV show, depicted reverently, authentically and beautifully, makes me feel a little less alone.