I stutter. Always have. I remember being 2 years old and struggling to push out the word “d-d-d-daddy.”

I also remember:

- Every time I couldn’t say my name and somebody would joke, “You don’t know your own name?!?”

- Sitting in class, drenched in sweat, the back of my neck burning up, while the kids read out loud, one by one, up and down the rows.

- Calling a friend’s house, their mom or dad answering, and me blanking on letters, gasping for air, until they hung up, thinking it was a prank call.

See, like many of you, I was born with this lovely trait in which, despite not being able to remember what I had for breakfast this morning (did I even have breakfast?), I can tell you, in painstakingly clear detail, every mean thing ever said to me — and every time somebody laughed at me for stuttering.

On the “that sucks” scale of 1 to 10, 1 being “I bought regular milk instead of organic” and 10 being “I accidentally put MiraLAX in my coffee,” this trait of mine is a solid 20. And here’s why: When a person who stutters goes into a particular situation, they’re not only living in that moment, they’re simultaneously reliving every other time they were in that situation — along with every insult, jab, or sarcastic comment somebody threw their way.

What’s funny is that, even in my darkest days, many people who knew me well would say, “but I’ve never even heard you stutter!”

That’s because I mastered all the tricks — and the three million Americans who stutter know exactly what I’m talking about. After enough episodes of stuttering publicly and getting mocked, you learn to hide it. Your life becomes Operation: Do Everything and Anything to Avoid Stuttering. Some of these tactics include being able to instantly substitute one word for another if you think you’re going to stutter. Or ordering something off a menu because it was easier to say than what you really wanted. Or pretending to have laryngitis to avoid talking.

This is, more or less, how I spent my first 30 years: hiding from stuttering, while still wanting desperately to conquer it. The latter involved a combination of speech therapy and about two dozen other ways to come to a point of acceptance, including desensitizing myself to my fear of stuttering by going into situations and actually stuttering. On purpose. My biggest fear. But I did it. And, to my surprise, I survived. So I did it again. And again. And each time would be (slightly) less soul-suckingly agonizing than the time before.

In doing this, I learned a lot about myself. For starters, I learned that I was much more than my stuttering. I also learned that I wasn’t going to let it define me or dictate my choices anymore. Finally — and this one really blew my mind — I learned that people were actually more interested in what I was saying than how I was saying it.

These days, I’m a creative director, where I’m constantly giving presentations, pitching work, directing actors on shoots, and basically living 8-year-old Rob’s biggest fears every day.

I think about 8-year-old Rob a lot. I wish I could tell him the magic cure he’s praying for isn’t going to come; that he could ignore the well-meaning teacher who suggested finding a career that didn’t involve talking (circus clown was actually mentioned). I’d tell my younger self that, believe it or not, one day, he’d learn to not only accept his stuttering but to also view it as a gift that would make him both stronger and more empathetic. I’d tell him that he would always be a person who stutters, and that’s OK.

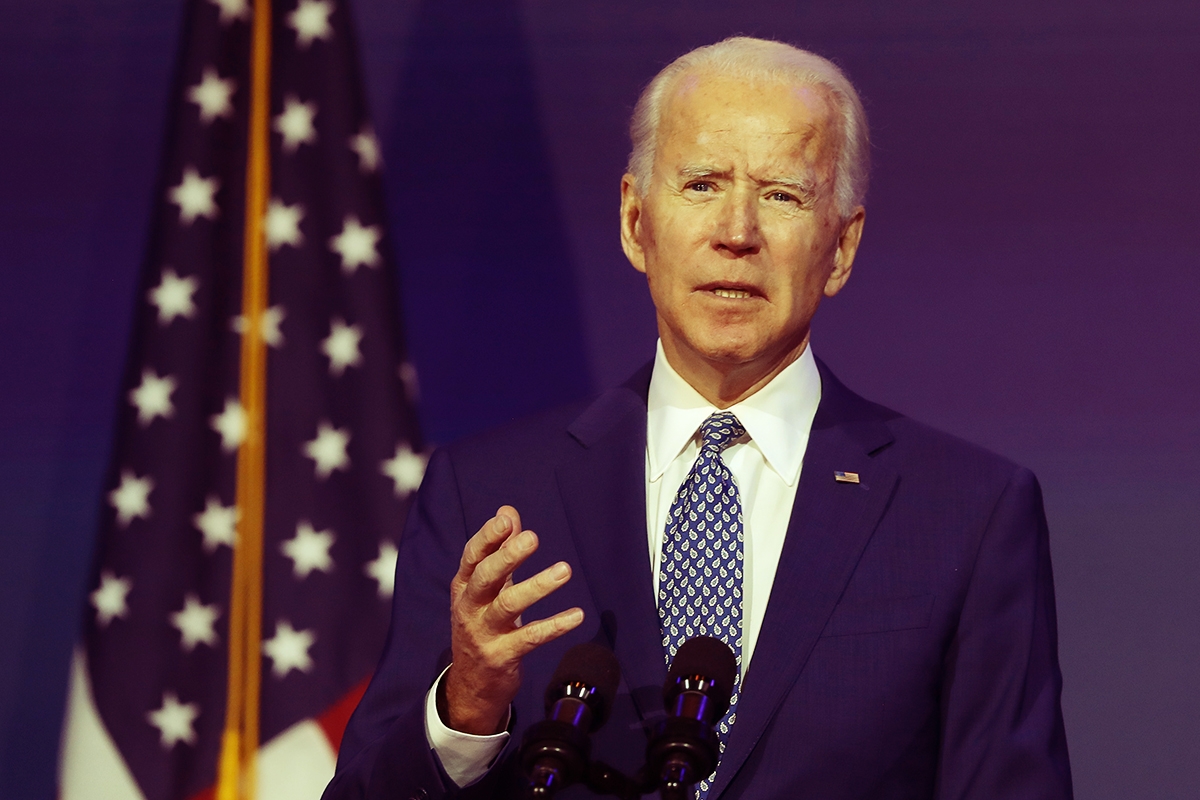

Then I’d tell 8-year-old Rob something else: That, in the year 2020, someone who stutters would be elected President of the United States — by more votes than anybody else in history.

It’s been one week since President-elect Biden’s acceptance speech, and I still tear up when I think about what this means for me, and everyone else who was ashamed of their stuttering. Essentially, America picked the kid who stutters over the bully.

President-elect Biden did not let his stuttering define him — and he certainly didn’t let it stop him from achieving his goals. That’s the lesson I want my kids to learn from this. After all, we all have something we’re struggling with. Maybe even something we’re ashamed of or hiding from. And while there’s more than one way to confront a challenge, there’s a tool that can help. It also happens to be a central Jewish value: persistence.

Rabbi Shimon Schwab, a famed rabbi and scholar, once wrote that someone can only accomplish something of significance through struggle.

King Solomon wrote in Proverbs, “even if a righteous person falls seven times, he will get up.”

And today, in the Year of Coronavirus, Rob Bloom, while not a rabbi but as someone who can eat his weight in latkes, writes, “never give up.”

The truth is, Jews have been practicing persistence for just about forever, from wandering in the desert for 40 years to Adam Sandler recognizing that one version of “The Hanukkah Song” just isn’t enough.

I don’t know if my own persistence is a factor of my Judaism, my stuttering, or my parents who set a pretty great example of what persistence can accomplish. It’s probably all three. All I know is that I wouldn’t be out of hiding if I hadn’t been persistent in my quest to lead the life I wanted to lead. For that, I am eternally grateful — just as I’m grateful to see President-elect Biden embrace his stuttering en route to rising to the highest office in the country.

Thanks to Biden’s relentless persistence, millions of people who stutter — particularly those kids who feel alone and ashamed — can now hold their heads just a little bit higher, knowing that there is no limit to what people who stutter can achieve.

Header image by Joe Raedle / Staff / Getty Images