This article is part of Back to School? a series on pandemic parenting and school reopenings, co-published by Kveller and the Jewish Telegraphic Agency.

In the last academic year, Syracuse Hebrew Day School had a grand total of 34 students enrolled in grades K-6, down from a high-water mark of 165 students decades ago.

The 60-year-old school in central New York, the only Jewish day school for 75 miles, has seen its fortunes sink along with those of its city. Once an industrial hub, Syracuse has declined in population from a peak of 220,000 in 1950 to just over 142,000 today.

But with the city’s public schools signaling that they are unlikely to reopen for full-time in-person instruction in the fall, Syracuse Hebrew Day School is anticipating its first major bump in enrollment in memory.

Its head of school, Laura Lavine, told the Jewish Telegraphic Agency that the school expects as much as a 40% increase in enrollment in the fall, when it plans to open full-time for in-person instruction with mandatory mask wearing and social distancing requirements.

Some of that is driven by families that have relocated from elsewhere to escape the pandemic — one prospective family called Lavine from Brooklyn after overhearing someone in their apartment building say they were moving to Syracuse. But most of the interest is local.

“My phone is ringing every day with questions from prospective families,” Lavine said. “And the reason for that is the public schools are still trying to figure out what they are going to do.”

Lavine’s experience parallels that of many day schools this year. Far from facing devastating enrollment declines, some Jewish day schools are finding that the pandemic is bringing them new students — particularly if their facilities enable them to space out students sufficiently to permit a full five-day schedule.

“We are picking [that] up in a lot of places,” said Paul Bernstein, CEO of the Jewish day school network Prizmah. “There’s a lot of interest from students at other schools. Jewish day schools of course are doing their best to accommodate the interest they are receiving, but it won’t always be possible given all the restraints.”

But the enrollment surge is uneven, with many schools in the New York City area, where most day school students live, contending with enrollment declines. And continued uncertainty about whether and how schools can safely open means much could change between now and the start of classes, in most places next month.

Bernstein said the trend of increased interest seemed particularly strong in suburban communities, where families have stayed put and in some places seen that their local public schools were not able to pivot to online learning as quickly as nearby day schools.

“Some of the contrasts that people are experiencing between Jewish day schools and other schools, including public schools, is happening in wealthier areas,” he said. “What they’ve managed to offer is nothing like what Jewish day schools have offered.”

That’s one factor that Lena Kushnir, head of school at Solomon Schechter Day School of Metropolitan Chicago, said she thought had driven “insane” levels of interest from new families. The school offered full-day online instruction within days of closing in March, while public schools in the area adjusted more slowly.

“We didn’t have to go through a whole hierarchy of structures of 10 schools in the district to make sure we could make it happen,” Kushnir said.

Now her school is planning on full-time in-person instruction this fall, and families are flocking to it. The school is holding an event for 35 prospective families next week, and Kushnir anticipates as many as five to 10 could wind up enrolling their children.

In Brooklyn, the Hannah Senesh Community Day School is also fielding inquiries but may not be able to accommodate everyone who wants to attend. The K-8 school is planning to reopen in the fall with full-time in-person learning for younger students and a blend of in-person and online learning for older ones.

Head of School Nicole Nash said she’s had inquiries for every grade level, but doesn’t expect to be able to accommodate them all given space limitations. As it is, the school intends to use every inch of available floor space, including the gym, library and art room to accommodate an anticipated increase in enrollment from the 220 students who attended last year.

“At a minimum we’ll hold steady, but I anticipate some incremental growth,” Nash said.

Like Hannah Senesh, other Jewish schools in New York City have seen increased interest as it became clear that the city’s public schools will not be opening with a full-time in-person schedule this fall.

But the schools also have been coping with the loss of families who left the city to escape the pandemic. Hundreds of thousands of New Yorkers have vacated their homes in recent months, often from wealthier neighborhoods, and whether and when they will return is unclear.

Beit Rabban, a nondenominational K-6 school in Manhattan, also is bracing for a decline in enrollment this fall from the more than 140 students it had anticipated, according to a recent report in Tablet. The school’s director said she was most nervous about the effect of families moving out of the city.

Luria Academy in Brooklyn also anticipates a dip from the 320 it expected prior to the pandemic even as it ramps up its search for additional space to permit the necessary social distancing.

“It is my sense that most day schools are down in the city,” said Amanda Pogany, Luria’s head of school.

Some schools are better positioned than others to weather the crisis.

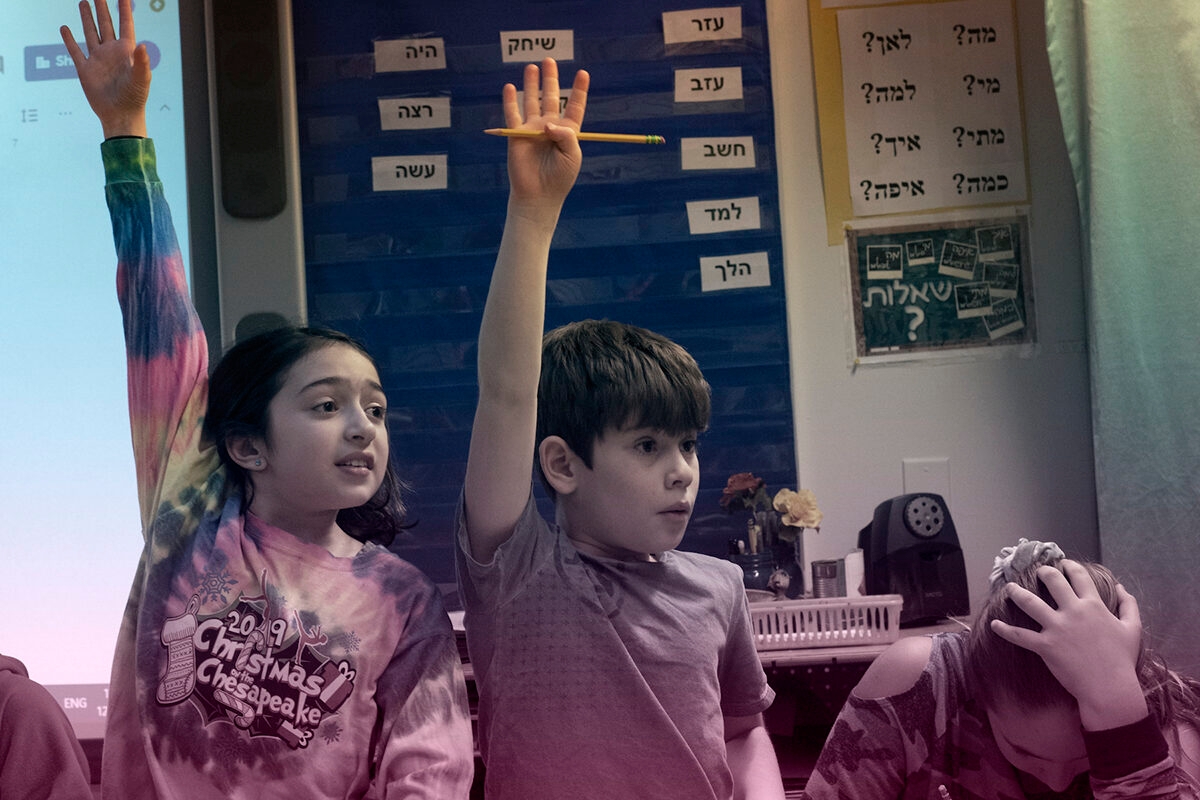

Students at Syracuse Hebrew Day School.

In New Rochelle, just north of New York City, Deganit Ronen said she expects increased enrollment at Westchester Torah Academy. The Modern Orthodox day school has incorporated online learning since it opened in 2013, making it an attractive choice compared to other schools just now learning to use online tools to teach. It also boasts a relatively low price tag — a potential boon for newly cash-strapped families for whom attending day school is an important value. Ronen, the head of school, said interest in her school was coming largely from families whose children have attended other day schools in previous years.

In Los Angeles, where public schools are going to be entirely online when the school year commences in August, the Kadima Day School was hoping to see a 10% jump in enrollment in the fall. With just 250 students and a large campus, the school was confident it could safely open on a full-time basis while maintaining 6 feet of distance for all students.

But that plan was thrown into disarray earlier this month after Gov. Gavin Newsom announced that the pandemic remains too severe to permit in-person instruction in Los Angeles. Now, Head of School Steven Lorch hopes his school may be granted a waiver, but the situation remains fluid.

“Everything is a little up in the air,” Lorch said.

Efforts to reopen have been strained as well by mounting economic concerns. At Kadima, the reopening plan has required hiring more custodial staff to keep the facility sanitized, improving the ventilation system and installing various types of protective equipment — all while coping with a 30% increase in requests for tuition assistance.

At Adat Ari El, a K-6 day school in Los Angeles, administrators are installing 360-degree, voice-activated Owl Pro cameras (retail price: $999) in every classroom to facilitate virtual learning, along with Plexiglas barriers and other protective equipment. Meanwhile, the school is facing “skyrocketing” requests for tuition assistance that Sarah Schultz, the interim head of school, said it won’t be able to fully meet.

“Every day we have meetings about this to figure out what we can do,” Schultz said. “We are still a community and we want to stand behind our families and be there for our families in this time of dire need. But we can only do so much.”

In Syracuse, that’s less of a concern. Enrollment was already so low that the school can accommodate many more students without taking on significantly expanded costs. The bigger question is whether the school can sustain the enrollment bump once things return to normal.

“Recruitment isn’t just recruitment,” Lavine said. “It’s about retention. We are mindful that once things open up, there’s a vaccine, you might find some of these families returning to public school. Our job is to continue to offer a superb education.”

Header image courtesy of JTA/Hannah Senesh Community Day School. This piece originally appeared on JTA.