Fans of Jewish artist Marc Chagall are well aware that much of his vibrant, modernist paintings are steeped in Jewish tradition. From scenes of biblical stories, such as Adam and Eve (1912) to shtetl-inspired paintings such as The Violinist (1910), Chagall’s work was heavily influenced by his Jewish upbringing.

Chagall (1887-1985) grew up in Vitebsk, a city in Belarus, though it was once a part of the Russian Empire. Chagall’s father worked at a herring warehouse and his mother ran a small shop selling fish and spices; the Chagall family lived amongst a Jewish community that numbered some 34,000 in 1897. His Jewish education was rich: He attended a Jewish elementary school, or heder, and his family, which included eight siblings, were active at the Great Lubavitch Synagogue of Vitebsk, which was once a hub of the city’s Jewish life. The family were “regulars” at the shul, according to Shalom.by, a Belarus Jewish news site.

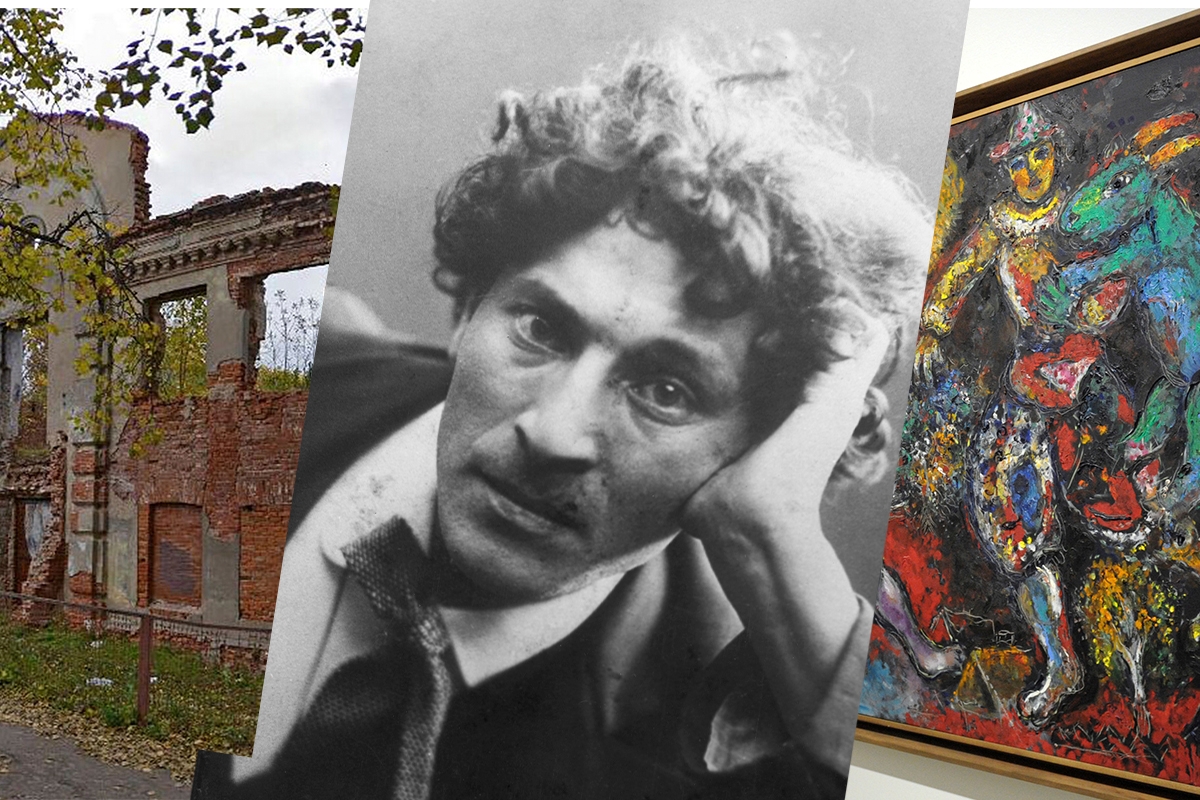

While Vitebsk boasted a strong Jewish community through Chagall’s childhood, the population began to decline as Soviet rule took over in the 1920s, with many Jews using their right of relocation to emigrate from the Russian empire, while synagogues were confiscated and Jewish schools were shut down in Vitebsk. In 1941, the Nazis took control of the city, and the Soviets responded by starting a fire and destroying much of the city. Today, the Great Lubavitch Synagogue lies in ruins; only the roofless skeleton of the building remains.

But, fret not, lovers of Jewish history: This once great synagogue is quite literally up for grabs! Last week, our partner site JTA reported that the dilapidated remains of the synagogue are for sale for a nominal fee — or even for free — and is offered with considerable tax breaks for investors. There’s only one catch: The new owner must be willing to conserve the ruins or restore the historic structure.

Of course, this is no small task — especially amid a pandemic, with so many of us juggling childcare and work responsibilities, all while trying to keep our loved ones safe. But let’s indulge our wildest HGTV fantasies a moment, and dream about how fun and meaningful it would be to return this important historic site to its former glory! According to Jewish Heritage Europe, the restored building doesn’t even need to serve as a synagogue (although it certainly could). Perhaps it could become a bed-and breakfast for art historians looking to visit the Marc Chagall Museum House — the former childhood home of the artist on Pokrovskaya Street— or the Marc Chagall Art Center, located on the left bank on the Western Dvina river.

Vitebsk, pop. 362,000, is the fourth largest city in Belarus. Prior to the Holocaust, half of the city’s population was Jewish; these days, the Jewish community numbers “a few dozen,” according to JTA. But the community throughout the area is slowly revitalizing — in fact, a new synagogue was built in 2017. With financial support from the city, the new Ohel David synagogue, built with Vitebsk’s signature red bricks, is designed to hold hundreds.

Despite living through massive historic events — Chagall’s life “spanned pogroms, two World Wars, the Holocaust, and the rebirth of the State of Israel,” according to our partner site, My Jewish Learning — Chagall remained deeply connected to his hometown and its culture. He admired painter Chaim Segal, a famed Jewish artist who painted three synagogues in three different towns in Belarus, eventually falling off his ladder and dying on the job. Given that Chagall’s original family name was Shagal — a variant of Segal — before he changed it to Chagall in order to help further his career, Chagall “adopted” Segal as his fictional grandfather.

After his childhood in Vitebsk, Chagall went to study art in the big city of St. Petersburg. It was there that he made prominent works like The Violinist (1910), which pays homage to the religious violinist in a village setting, which would become a favorite motif (Fiddler on the Roof, anyone?). After studying with magazine illustrator Leon Bakst, Chagall connected with Max Vinaver, who became his patron and sponsored his education in Paris. During his Paris years, Chagall continued to honor his soft spot for his homeland, painting works like Mother Russia (1912-1913) and I and My Village (1911).

Given Chagall’s deep connection to Judaism and his hometown, we at Kveller are so excited to see what will happen next to this historic synagogue. And if you, dear reader, are up for the challenge of restoring this building to its former glory, please drop us a line and let us know how it goes!

Header image via JTA/Courtesy of the Municipality of VitebskHulton Archive Stringer/FRED TANNEAU /Stringer