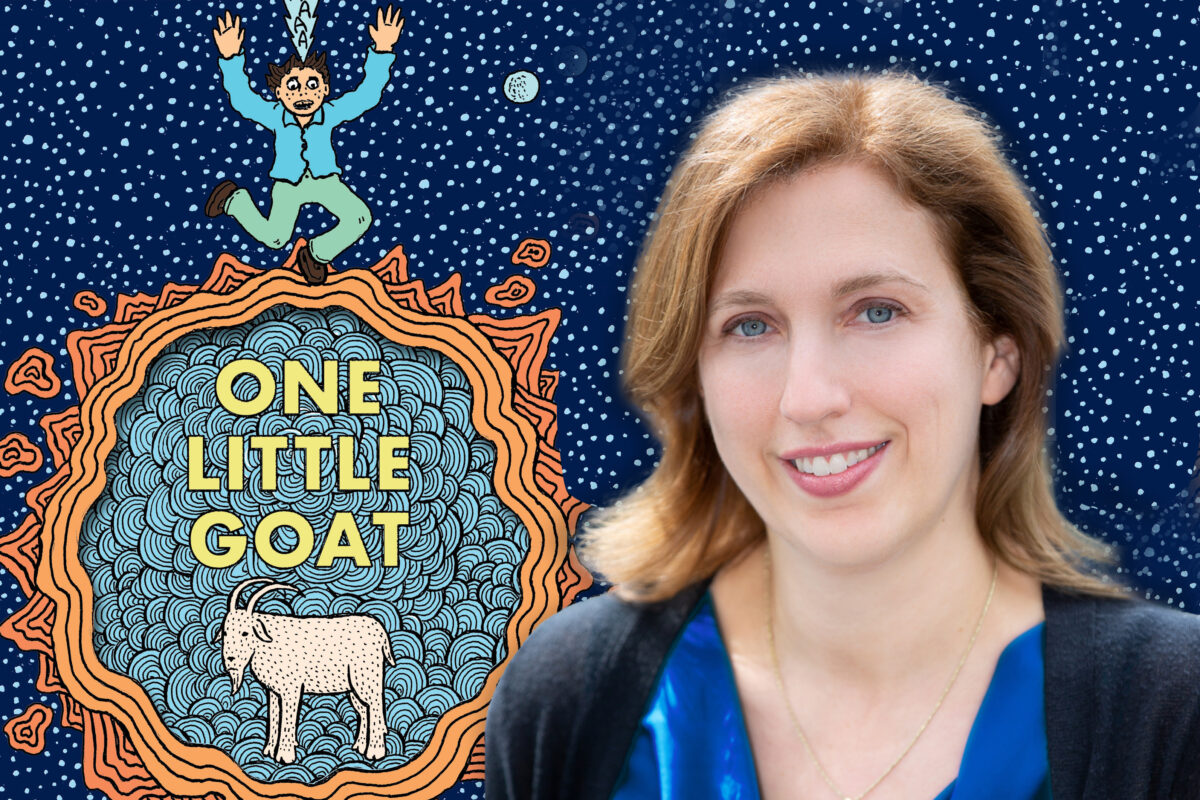

When it comes to “People Love Dead Jews” author Dara Horn’s first-ever children’s book, I tend to agree with Daniel Handler, aka Lemony Snicket, the Jewish author of “A Series of Unfortunate Events” and “The Latke Who Couldn’t Stop Screaming.”

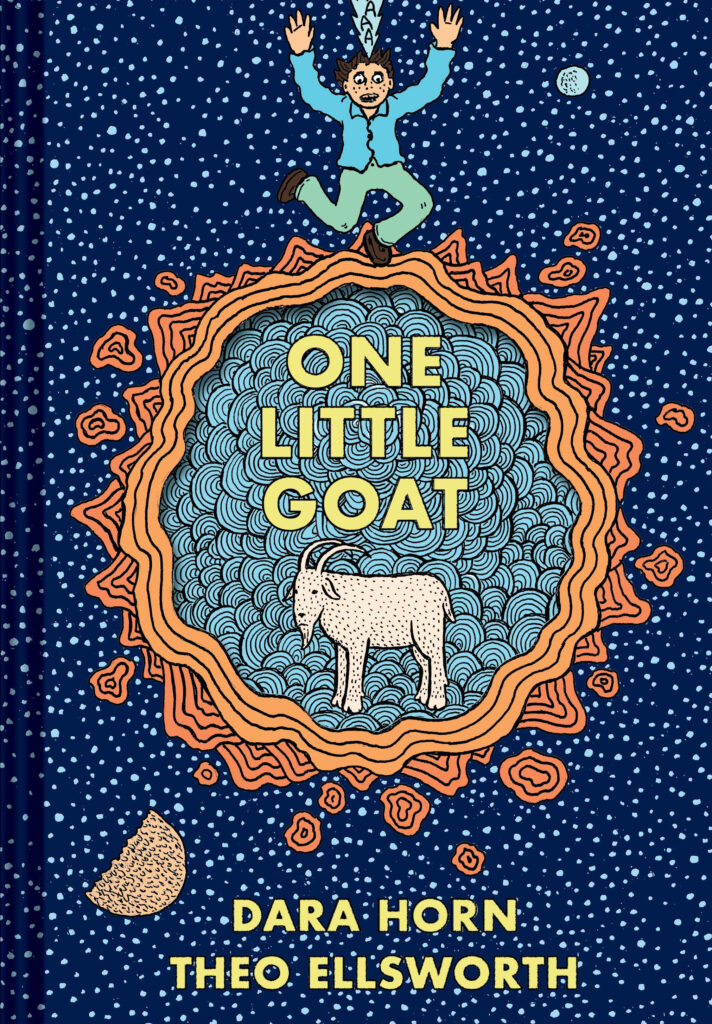

“At long last, here is the time-traveling goat-centric Passover adventure my people have been awaiting for thousands of years,” he wrote in a blurb for Horn’s upcoming graphic novel “One Little Goat,” illustrated by Theo Ellsworth, and titled after the translation of that final Passover seder song, “Chad Gadya.”

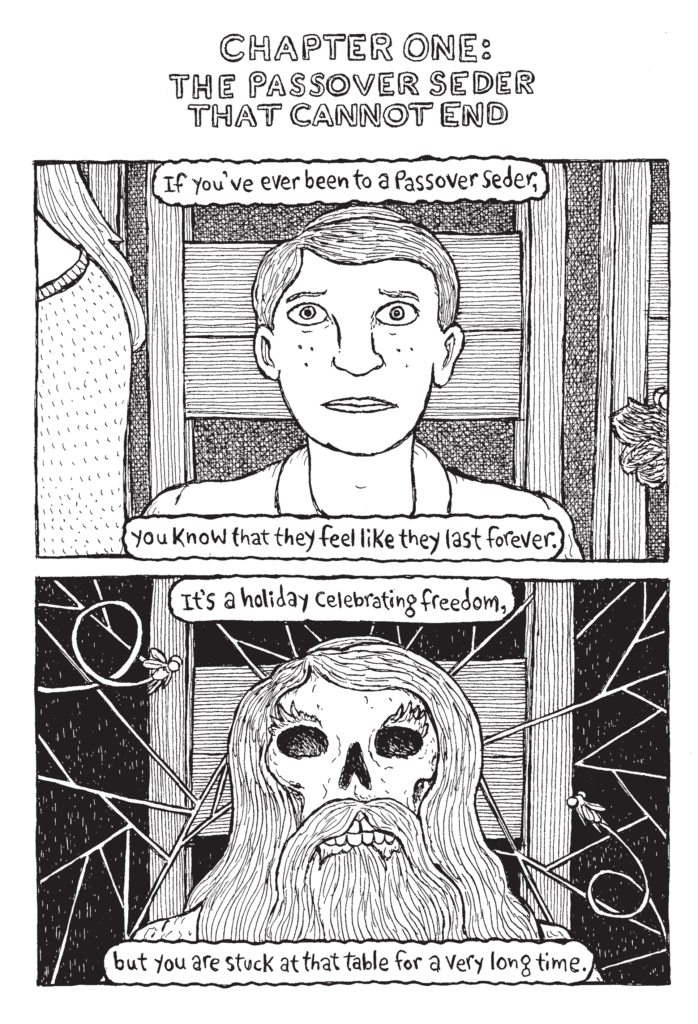

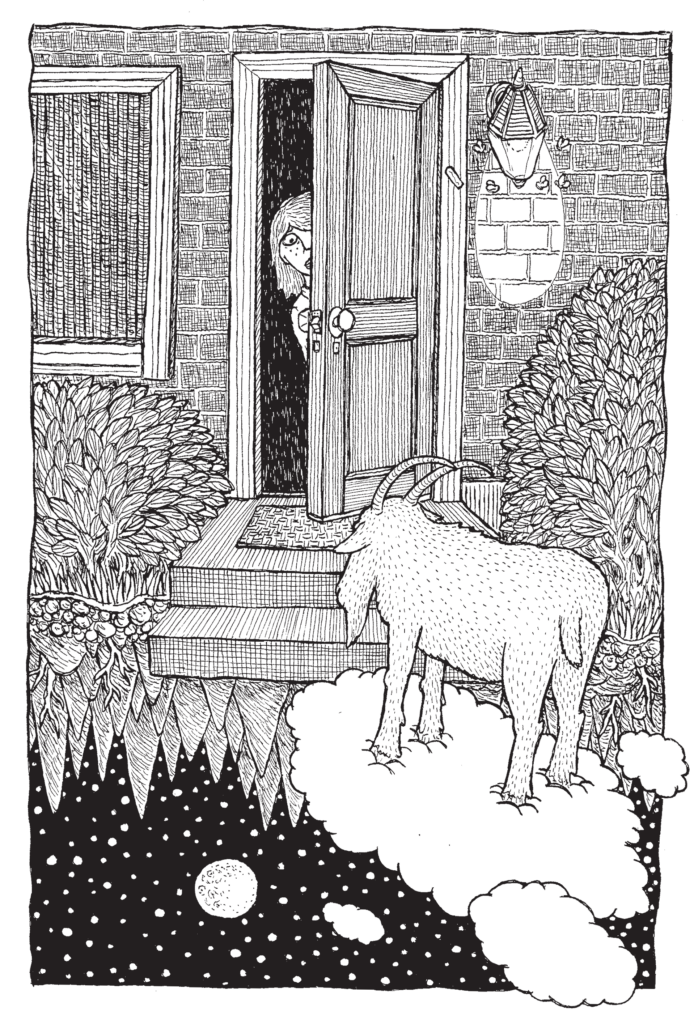

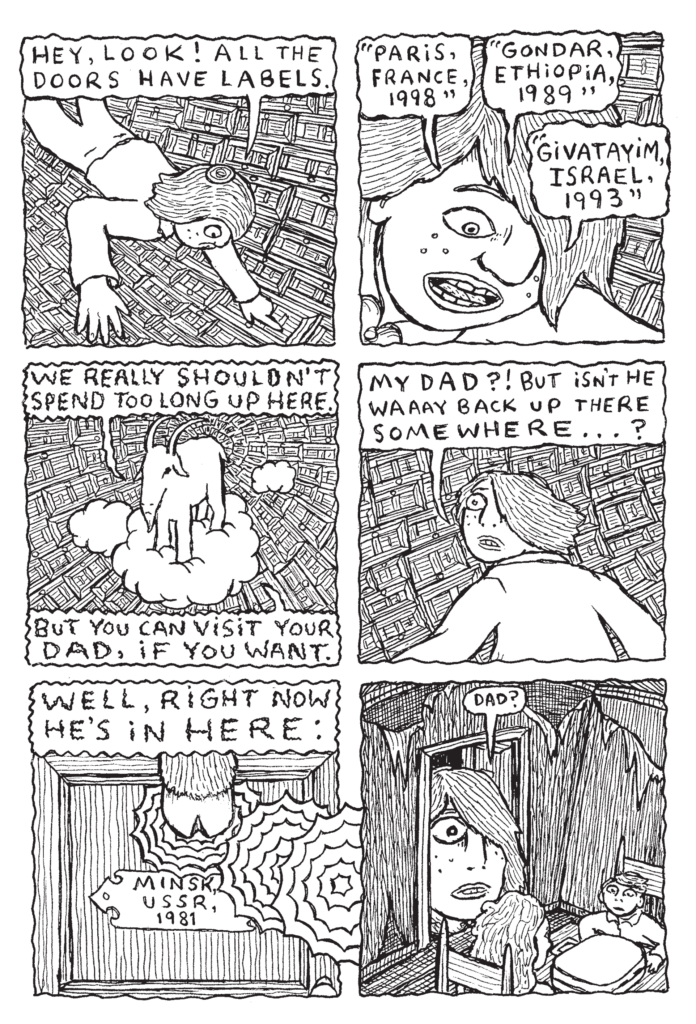

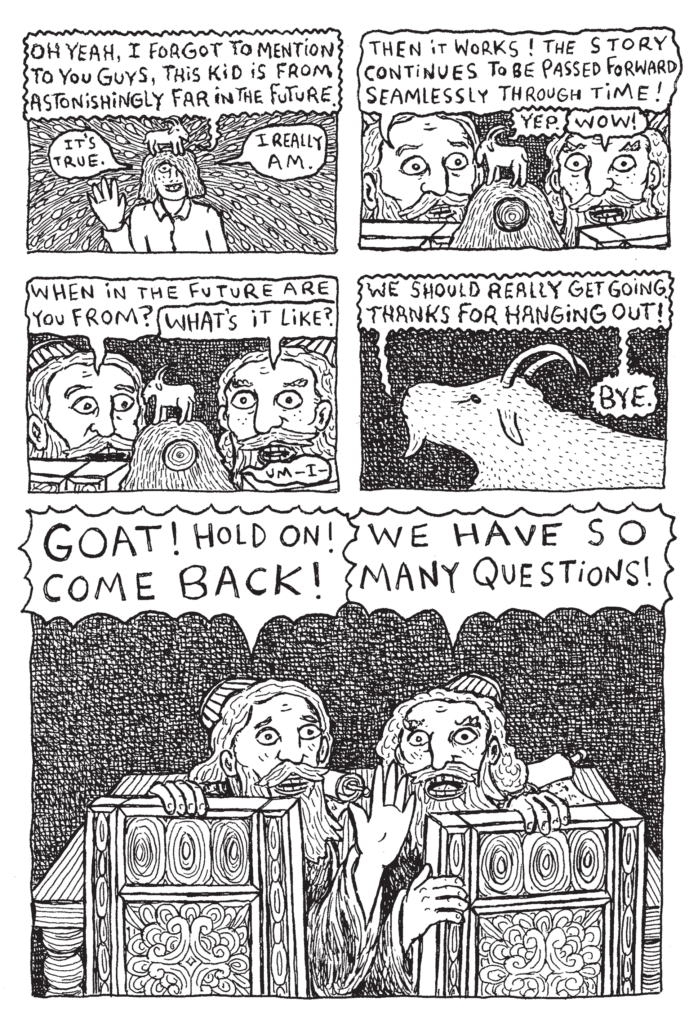

Now, there is a critical mass of lovely Jewish children’s fiction out there, from Josh Levy’s wonderful middle-grade novels about bar mitzvah time loops to charming books about baby namings and Passover feline guests, but “One Little Goat” feels like all my Passover fever dreams come true. In it, a young boy and his family’s very typical Passover seder goes on literally forever when the baby loses and cannot find the afikomen — that little dessert piece of matzah that needs to be found for the Passover meal to wrap up. Then there’s a knock at the door — a little talking goat who’s there to help.

“One Little Goat” has all the sensibilities of Dara Horn’s fiction: inventive, wild and deeply rooted in the Jewish experience, history and mythology. Ellsworth’s visual style elevates the book and makes it feel grungy and subversive, a cool (or “fire,” or “GOAT,” or “sigma,” or whatever the right word would be for young readers right now) story meant for kids to laugh with rather than anything preachy or didactic. Yet like Horn’s non-fiction “People Love Dead Jews,” it’s also a deeply timely lesson about Jewish history and resilience, and about just how special and magical Jewish tradition can be.

Here at Kveller, we’re super proud to reveal this books’ gorgeous trippy cover, the little goat at the center of a mandala-like sun on a background of stars, with our hero falling down from the top of the cover and a little round matzah half, the afikomen, as its own quirky planet. We also had the pleasure of asking Horn some of our most pressing questions about the new book, which comes out March 4, 2025.

I’m so excited for a Dara Horn graphic novel! Can you tell us a little bit about how this book came to be and why you felt it had to be told in comics form?

This is definitely going to sound bizarre, but I really feel like this was the book I was born to write. I’ve been obsessed with the Passover seder since childhood, particularly the feeling it gives of living inside a story that continuously reboots itself. When I was a child my family always hosted the first seder, during which my three siblings and I invented new creative retellings of the Exodus story, and then we attended the second night with friends who hosted a huge multigenerational gathering around a long table — at one end were Holocaust survivors, and the children were way at the other end, and these two groups were essentially attending two different seders. At one of those seders as a kid, I suddenly understood that this lighted room we were in was actually the top of a tower of lighted rooms containing everyone’s previous seders, going back down to the night of the Exodus. I’ve had that idea in my head for over 30 years.

It came back to me a few years ago during a road trip when my family stopped at a comic book shop, and one of my kids wound up buying Theo Ellsworth’s book “Capacity.” All four of my kids were fighting over this book on the way home, so I picked it up to see what they were so excited about. I’ve never been into comics, but I found myself absolutely enchanted by his artwork — the intricacy, the surrealness, the ease and humor with which he made abstract ideas visible and beautiful. It brought that Passover idea roaring back to me, and I couldn’t let it go.

What was it like working with Theo Ellsworth? His style is so perfect for this trippy story — it definitely connected me to that feeling that you get when the seder goes on for too long and you start to feel a bit disconnected from reality.

That’s exactly the feeling I was going for — and I think the Jewish tradition intends us to feel that way, to experience that release from one’s own time in order to enter into the timelessness of this story. In the book, that release becomes absurdly literal.

Theo is fantastic. I literally cold-emailed him, gushed about his work, and then said, “Okay, deep breath, let me explain this idea I have…” He isn’t Jewish and the basics of the story I had in mind were new to him, but he was completely game and really excited to dive in. I included a lot of art direction in the manuscript of how I envisioned things looking on the page, but his ideas for visuals were (of course!) invariably much cooler than mine. He illustrated chapter-by-chapter in pencil and then we’d go back and forth making adjustments — but generally the adjustments were minor because his work consistently amazed me. With some of the Jewish sources, I’d give him a lot of options and he’d run with what inspired him, like the Birds’ Head Haggadah from the Middle Ages and another medieval haggadah that depicts the Four Children as playing cards. It was amazing to watch him bring these ideas to life.

The idea of a Passover seder lasting forever is certainly a nightmare scenario for many Jewish kids. Was that how you felt at seder growing up? How does the seder in this book compare to your Passover experiences?

I know that’s a common experience, but my parents always insisted on making me and my three siblings bring the story to life. Each year we’d write new songs and skits and parodies that we’d perform alongside the traditional liturgy, and that made our seders endlessly entertaining.

For the past 13 years I’ve hosted seders for our family, including my parents’ 14 grandchildren. We do the whole traditional liturgy, but it’s interspersed with creative interpretations, and at this point our Passover productions are completely over-the-top. We film our parody videos in advance (like this hilarious 90-second spot from a few years ago, a “Succession” parody featuring my four kids, called “Oppression”), but we also build an elaborate walk-through immersive experience in our basement and garage, with blacklights and neon-painted Egyptian tombs and costumed actors as Moses and Pharaoh and the Angel of Death and a laser swamp for the parting of the sea. That’s on top of other things like the ceiling plague-drops, the smashing of clay idols, the LED-illuminated puppets for “Chad Gadya”… My kids have no idea that other people find seders boring.

“Chad Gadya” is almost an addendum at the end of the seder but for some reason I also remember the goat being the most inspiring part of the seder (so does Jack Black, apparently). Can you tell us a little bit about the goat at the center of this book?

The idea of a “scapegoat” comes from the Torah ceremony for Yom Kippur in ancient times: The high priest would symbolically place the sins of the people on a goat’s head and then release the goat into the wilderness. For non-Jewish cultures this “scapegoat” idea is a source of pity, but I’m a scholar of Hebrew and Yiddish literature, and I had noticed how often goats appear in Jewish literature as much more affectionate figures, representing a kind of stoic integrity.

The medieval song “Chad Gadya” at the end of the seder is often interpreted as representing Jewish history. The “one little goat” represents the Jewish people, who “my father bought for two zuzim” — the father represents God, and the two zuzim (coins) represent the two tablets of the Ten Commandments. The various predators in the song are the different empires that conquered Israel, all of which wind up conquered themselves and vanquished. And even though the goat gets eaten, somehow he keeps reappearing as the song returns to the beginning over and over again.

To me this idea of the Jewish people as the scapegoat is something very powerful, not only because of the negative aspect of antisemitism’s persistence, but also because of the way that history has instilled a kind of integrity and resilience.

The goat in the book is the personification of that history. He has a deep integrity that children slowly learn to recognize. He doesn’t ask why people hate him or blame himself; he’s thoughtful and resourceful and always hilarious. He understands that this unearned hate is the way of the world, but he also understands his own endurance and power and inventiveness. The boy in the book learns to admire him. To me this is about young people coming to understand their place in this history, which isn’t really a history of horror but rather a history of mind-blowing creativity and resilience.

Your adult books, especially “People Love Dead Jews,” have definitely helped a lot of people navigate and illuminate this current moment for American Jews and Jewry around the world. What do you feel is the significance of putting out a children’s book that’s so full of Jewish specificities and experiences right now?

I started working on this book before I published “People Love Dead Jews,” so that wasn’t really on my mind when I came up with “One Little Goat.”

“People Love Dead Jews” was responding to the rising tide of antisemitism, which has gotten exponentially worse since I published it. Facing this organized effort to push Jews out of public life is especially hard for young people, and the grown-ups have been forced to pay a real tax in terms of devoting their resources and energy to pushing back against this hate. This book doesn’t ignore that problem, because that problem is inherent in the Passover story. But it introduces that problem through a story that brings readers in with a lot of joy and humor, and confidence and courage.

What are you hoping that young readers take from this book?

I hope they’ll have a blast reading it! But I also hope they’ll see how they are characters in this story that started thousands of years before they were born, and how this story cannot continue without them. As the family in the book tells the boy at the very beginning and again at the very end, “We’ve been waiting for you.”

You can pre-order “One Little Goat” on Bookshop.org, Amazon and wherever else you find your books.