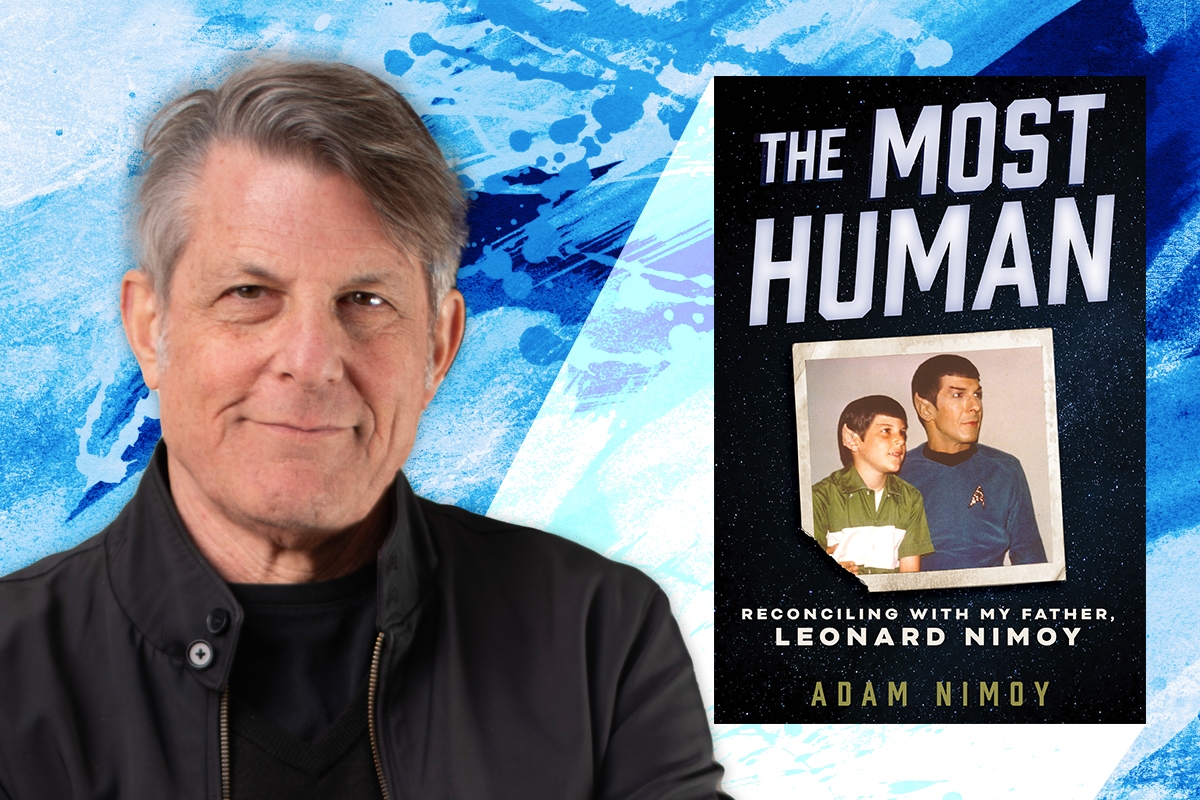

The night before I interview director and writer Adam Nimoy about his new autobiographical book, “The Most Human,” I watched the 2016 documentary he made about his father, “For the Love of Spock,” and cry.

“For the Love of Spock,” released a year after the “Star Trek” actor Leonard Nimoy’s death, is dense and funny and geeky. It’s full of moving tributes to Nimoy, the son of Ukrainian Jewish immigrants, from co-stars and fans. And while I’ve always known that the Vulcan salute from “Star Trek” was based on the Kohanim, or priestly, blessing, seeing it explained in the film was incredibly moving, knowing it was a symbol that Nimoy was exposed to at his own childhood synagogue. Here was a man, back in the 1960s and ’70s, who brought a deeply mystical Jewish symbol to all of America and beyond, and just like the blessing itself, it was passed on from one person to another, generation to generation. Married with the words “live long and prosper” — well, it hit quite deep.

Judaism was infused into Leonard’s son Adam’s life as well. “The Most Human,” out this week, starts and ends with Yom Kippur services, and just like Yom Kippur itself, it is a tale of atonement, perhaps the most important kind of atonement one can experience in a lifetime — that between a parent and a child. It’s both a heavy and at times breezy read. Nimoy doles out little tales of his life, passing them down from generation to generation. These vulnerable stories are about his father, yes, but also about his mother and her struggles, too; about his two children and his ex-wife; about his late second wife who died of cancer; about addiction; and about his work.

Telling these stories is the way Adam has always connected with his father. “My real connection with my dad in all honesty was a lot about me telling him stories,” Nimoy tells Kveller over Zoom. Theirs was a relationship “about storytelling.”

“I would entertain him, to try to reach out to him and connect with him. It would be stories about what I’m teaching in school, in my film classes, stories about while I was directing on set… stories about my kids. I was always telling him, ‘Dad, I gotta tell you what happened.’ He was very taciturn; he could be very distant, even when he [was] feeling OK towards me. He was just very introspective. That’s just his personality.”

It’s hard to connect this image of Leonard Nimoy as a father to that of him onscreen, or even on stage at press and fan events, where he would talk effusively and come across as funny, intelligent and charming. Yet for a lot of his life, Adam and his father didn’t get along. It didn’t help that for years, Adam was blunting his feelings with weed, while his father was numbing his own with alcohol. It especially didn’t help that Adam had to constantly experience the contrast of seeing his father as a cultural icon, this savior with a kind and calm public persona, when that was not what he experienced at home. Adam says they were possibly doomed from the get-go: himself, a son who grew up mostly in “Star Trek” affluence in Southern California, and his father, a man raised by immigrant parents in Boston in the height of the Depression. Whatever it was that made them like oil and water, it weighed heavily on Adam for much of his life. He would see his father be kind to fans and his film students and think to himself, “Why aren’t you available for me? Why aren’t you present with me?

In a wonderful hour-long conversation, in which Adam is as charming and wise as his father always seemed to be, Adam tells me stories too — like the one time he went to the dry cleaners after a particularly rough argument with his dad, and the man, realizing he was Spock’s son, said, “He must be a wonderful father,” telling him how the character of Spock saved his life during college. All Adam could think was, yeah yeah yeah, that very man just chewed me out for an hour, just give me my clothes.

But reading his book, it’s easy to see how much the Nimoys, father and son, had in common. Both writers — Leonard released his own autobiography, “I Am Spock,” as well as poetry collections and a photography collection called “Shekina;” both lovers of storytelling; both addicts who went on a road of recovery after or as their first marriages dissolved. Both parents. Both in the entertainment industry. Both passionate about politics and the Jewish concept of tikkun olam, healing the world. Both had difficult relationships with their own parents — Leonard’s parents didn’t want him to be an actor. Both found a way to connect to Judaism in their life and work. They even look alike, but that may just be confirmation bias. Would I know he was Leonard Nimoy’s son if I just saw him down the street, he wonders? Maybe he just has a “Jewish patriarch” look.

“He was so emblematic of our patriarchs,” Adam, who mentions the story of Abraham and the Binding of Isaac early in the book, tells me. “He looks like Abraham. He was so majestic. My dad and the power that he had over the world is something that’s not too far away from the influence of Abraham over the last 3000 years. It’s pretty powerful, the effect that Spock has had on the world, and the [Vulcan Salute] is known all over the world. But the weird part of it is that even though we connected on storytelling, Bible stories were not something that occupied our time.”

Adam Nimoy grew up in a Jewish home, sort of. He went to Yom Kippur services and they had Passover seders, but in the book, Adam shares that “although [Leonard] was steeped in Jewish culture, I would not call him a religious man.”

“There were a couple of occasions where I was very aware that my father was going to work on Yom Kippur, and I didn’t say anything. But it bothered me, because I would never work on Yom Kippur,” Adam muses. “I told my agent when I was working in Hollywood: I don’t work on Yom Kippur. He called me the Sandy Koufax of TV directors. And I had to pass up some jobs. There was a Steven Spielberg series, and I told them my problem, and they wouldn’t let me out that day.”

Yet Adam understands why his father pulled away from religion. “He was raised in a very Orthodox type of household, and so was my mother, and I think that they were a little bit like, ‘enough is enough, I need to live my own life,'” he says.

Antisemitism didn’t really touch Adam’s life nor his father’s as much as he could tell. “He was fearless. Coming out as a Jew, participating in Jewish stories. He did audiobooks about Isaac Bashevis Singer. He was in ‘Fiddler on the Roof.’ He did interviews where he shared the fact that he spoke Yiddish,” Adam recalls. He was clearly proud of being Jewish. In fact, one of the people who Adam still often shares stories with is theater director Ben Shaktman, who directed his father in “Fiddler” (Nimoy played Tevye, of course, another great Jewish patriarch) and “The Man in the Glass Booth,” in which Nimoy played a complex Holocaust survivor.

A lot of “The Most Human” is about the push and pull of Jewish generations. Adam’s grandparents, with whom he was very close, were very observant, his father less so, and Adam himself found a special connection to Judaism, a closer one, especially as a recovering addict.

“I’m very connected to Beit T’Shuvah,” a residential addiction treatment center in LA, he tells me. “I go to Shabbat services every Friday night. I study Torah on Fridays with the rabbi. I’m heartbroken about the world today, the war and antisemitism. But you know, I’m also a student of history. And we’ve seen this over and over and over again. We’re just going to have to get through, but it’s disheartening.”

Does he ever wonder how his father would react to this present moment, I ask him?

While he knows his father would always do what he could to stand up for Jewish people, he knows that current politics are complicated. “I think my dad and I would be talking about this a lot more,” he tells me. “He would be thinking very hard about what he could do to help repair the world. That’s who my father was.”

A lot of children of celebrities have a complicated feeling about their relationship with their parents’ fame. Adam doesn’t seem to at all. First off, he’s truly a fan of his father’s work — especially of Spock and his wisdom. He also acknowledges that his relationship with his father was the most pivotal relationship in his life. Most importantly, his desire to tell this story, about the very real and imperfect way he and his father made amends and healed their relationship, stems from his desire to heal the world.

That path to amends came along much later in life, as Adam made amends to his father after he sent him a particularly dramatic letter, as well as a pivotal moment when Adam’s late wife, Martha, fell ill. “He was my emotional support while my wife was sick,” Adam says, “and became the father that I always wanted and needed.”

Even before the publication of this book, that story inspired people to seek out a similar atonement with their loved ones. When he’s shared it anonymously at the Al-Anon and AA meetings he still attends, people come up to him and tell him, “I’m going to call my dad, I’m going to call my mom, I’m going to call my brother and my sister. I’m going to try again, with the tools of recovery, and see if I can reach out and repair our relationship.”

Ultimately, he hopes that this book resonates with readers and maybe inspires them to mend any broken relationships of their own.

“If I had been given a choice of having a dad who was not so successful, had a little more mundane lifestyle but was much more loving, or a dad who was going to fly across the universe and give me a life that was incredibly interesting, but he was gonna sometimes be a son of a bitch, I would have said, ‘OK, I think I can handle the son of a bitch. I would have picked him. I did pick him.”

His journey of recovery and acceptance made Adam Nimoy a better son, but perhaps even more importantly, a better father. He’s learned how to be more sensitized and present, to not make the mistakes of his father. The most important thing he learned about parenting, through recovery, is to just be there. “I want to let my kids be who they are, and not get in their way.”

“The great thing about not being high or drunk is I’m always available 24/7 if they need me. I’m supportive, and I am nonjudgmental,” he says.

His daughter Maddy works in movies and TV production, and his son Jonah is a drummer in a fun little band you might know — the Offspring — who at age 32 is touring the world.

That isn’t to say that his relationships with his kids are perfect. Adam regales me with another little story, of going to dinner with his son the night before and asking him to pull up his T-shirt because, while he is nonjudgmental, he is not a fan of his son being covered with tattoos. “I don’t have to see that you’ve got ink all over your chest and shoulders,” he told Jonah.

Jonah laughed and replied, “One of the purposes of my life is to irritate my parents.”

It’s a mission that remains true from generation to generation, from Jewish father to Jewish son. And yet it seems that in some ways, Adam Nimoy has healed a generational curse, letting himself have the kind of relationship with his children that he always wished he had with his father.

As our breezy interview wraps up and we say goodbye, Adam Nimoy lifts up his hand in that familiar gesture his father made so popular. “Live long and prosper,” he wishes me, and I clumsily salute back.