“The Survivor,” which premieres on HBO just in time for Yom Hashoah, Holocaust Remembrance Day, packs a lot in its dense two hours — perhaps too much. Directed by celebrated Jewish director Barry Levinson, the new movie tells the story of Harry Haft, a Polish Jew who quite literally fought for his life as a boxer in Auschwitz.

The film is worth watching solely for the haunting performances by its cast, especially Ben Foster who plays Haft. Throughout, he transforms from an emaciated Auschwitz prisoner to a strapping young boxer arriving in America to, ultimately, a settled middle-aged family man. The Jewish actor and father of two told the Jewish Telegraphic Agency that the role “expanded my relationship to the courage of those who left to come here.”

Danny DeVito is also surprisingly endearing as a source of comedic relief in the role of Charlie Goldman, a trainer who reluctantly takes on Haft. Goldman is a Polish Jew who has been in America for much longer than Haft, and the two bond over losing loved ones to the Nazis and their Hebrew names.

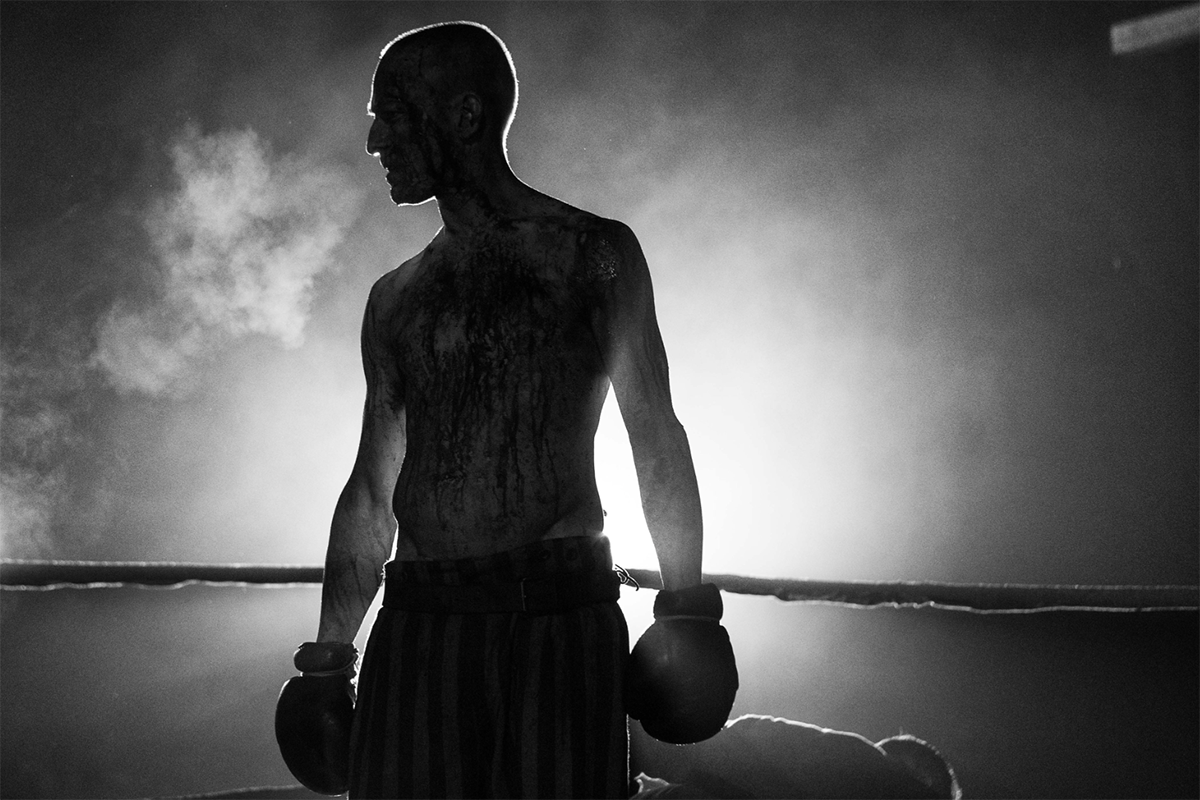

The movie doesn’t pull any punches when it comes to showing the horrors of the camps, from scenes of piling dead bodies to depictions of Haft’s mortal fights and all the many horrible things he had to do to survive. These flashbacks, in black and white, will not be unfamiliar to those who have seen many Holocaust movies — but they’re still wrenching to watch.

In flashback scenes to Auschwitz, Billy Magnussen plays Deitrich Schneider, the SS officer who takes Haft under his wing. While Magnussen is always excellent at playing a complex villain, the scenes between the two are perhaps the least enlightening in the movie. In the film, reporter Emory Anderson (Peter Saarsgard), who approaches Haft to write a story about the “boxer who survived Auschwitz,” tells him that the most compelling part of his story is “the common ground between good and evil… Nazi and Jew.” But finding empathy for your abuser is not a prerequisite to healing, and finding the humanity in Nazis does not make for a successful Holocaust movie.

Yet what is interesting, and what the movie is thankfully more preoccupied with, is how one actually lives after surviving such horrors. Haft tries to build a life for himself in America, but he is haunted by the trauma of his past. Knowing that most of his family has perished, he looks for his lost love, Leah, the woman whose memory helped him survive. That is how he meets Miriam (Vicky Krieps), who helps survivors reunite with their loved ones.

But trauma is still at his tail — in the middle of a fight or practice, when hearing fireworks overhead, and in his dreams. Even in his happiest moments, like on his wedding day, Haft is haunted by what he endured in Auschwitz, memories that, throughout most of the movie, he keeps to himself. As his best friend tells him, his is a story that shouldn’t be told — it’s too dark and too shameful.

Many children of survivors tell a similar story — that of a parent haunted by their past, but reluctant to share it, steadfast about wanting to embody a kind of strength and authority that was taken from them during the war. There’s certainly nothing that projects that authority more than Haft, a virulent powerful man — the exact opposite of what one imagines when they think of Holocaust victims.

Yet that steadfast insistence of resilience comes at a price. As his future wife tells him in one scene, it makes him kind of an asshole: a father who is too rough on his son, too closed off for his wife.

At the end of the day, Haft is able to overcome some of his trauma by telling his story, shedding its shame and sharing its burden — especially with his family. The moments that he opens up with his loved ones are particularly powerful.

But “The Survivor” often feels like it’s following some kind of an imaginary checklist of requirements for Holocaust movies — addressing everything from loss of faith, to the argument that Jews went like sheep to the slaughter, to the whiteness of Jews, to the psychology of Nazis. In trying to pack in so much, it, unfortunately, weakens the overall affect. Some moments feel too heavily didactic, others downright schmaltzy — though certain schmaltzy moments, like Haft’s reunification with his long-lost love (a luminescent Dar Zuzovsky), might still draw a tear or two out of you.

One thing that Foster’s casting eclipses from the story is just how young Haft was — just 16 when he was sent to Auschwitz. It’s something that would’ve added to the complexity of this tale.

The movie also lays on particularly thick the promise of safety that living in America held. On multiple occasions, characters in the show extoll how wondrous it is that they could create a life for themselves in the U.S. — certainly a feeling increasingly common for survivors. One of the final scenes of the movie includes a Yiddish rendition of “God Bless America,” the Irving Berlin song that premiered on the eve of Kristallnacht. It’s a moving scene, even if the movie glosses over the fact the country closed its doors to Jews it could’ve saved during the war, or that finding a home in America, still, to this day, doesn’t mean finding a shelter from antisemitism.

Ultimately, “The Survivor” also serves as a reminder of how younger generations have helped to keep the memory of the Holocaust alive. It is thanks to the real Harry Haft’s son, Alan, that we even have this story, which he recounted in a book, and which was then adapted into the award-winning and haunting graphic novel “The Boxer.”

“The Survivor” may not be the best Holocaust movie you will ever see. Yet it tells a compelling story that is worth remembering, and one that we can feel grateful to have.