The Jewish diaspora encompasses so many languages, from Ladino to Hebrew to Yiddish, to lesser known tongues such as Yevanic (Judeo-Greek) and Aramaic. For many Ashkenazi Jews, in particular, using Yiddish words can be a fun and humorous way to celebrate our heritage and our ancestors, while also helping to keep the language alive.

While the wonderful language of Yiddish has so much to offer — in particular, its colorful curses, such as “gay cocken oifen yam,” which means, “go shit in the ocean” — the age-old tongue can sometimes be at a loss for the unique situations of modern life.

Fortunately, author Daniel Klein identified this conundrum — and solved it. “Yiddish doesn’t have the vocabulary for the modern world of Google, mixed marriages, new gender identities, and many more aspects of contemporary life,” he tells Kveller.

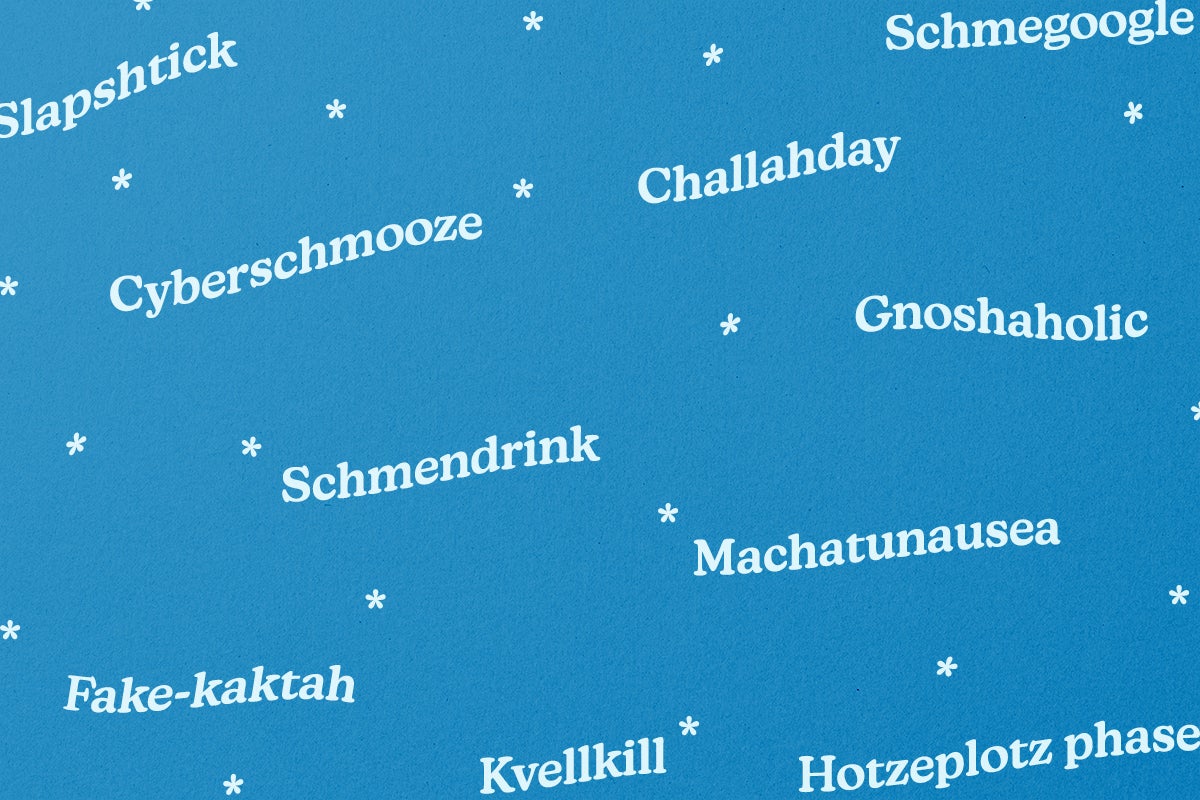

And yet, “as a language that picked up words as Jews emigrated from one nation to another, it has a capacity for adding new words to its vocabulary.” Drawing on his experience working in the writer’s room for TV host Merv Griffin, he created an updated vocabulary of new Yiddish expressions, Schmegoogle: Yiddish Words for Modern Times.

As evident in the book’s title — which combines Google with “a long list of Yiddish put-down words that begin with sch” like, schmuck, schlemiel and schlemazel to name a few — most of the words in this fun dictionary are a mashup of an English word or phrase with a Yiddish one, creating puns and expressions that will make you laugh, ponder, and appreciate the evolution of language.

Klein includes language on all topics, from food to family to technology. Here are some of our favorites:

1. Challahday n. Cute slang for the Sabbath, during which challah (braided egg bread) is traditionally baked and eaten. Klein adds that the term “has been generalized to mean any special day or vacation day, with or without bread.” We always love new ways to celebrate the beauty that is Shabbat!

2. Cyberschmooze v. To engage in long, animated, and gossipy conversation on the internet (where basically all interactions happen during these pandemic days). This word comes from the Yiddish word schmooze, which means to talk intimately or cozily. Klein adds that this word is especially necessary in modern times, as Jews love to “yak a lot, always have, and continue to do so in cyberspace.” Too true.

3. E-chazerai n. Accumulated unanswered emails. This word stems from chazerai which is Yiddish for “garbage,” or “pig stuff.” Klein notes that the Yiddish language has a knack for finding a variety of words that invoke pigs (and also, penises).

4. Fake-kaktah adj. Pretending to be a wild, colorfully kooky person — but not fooling anyone. As in, “There goes Millie with that fake-kaktah laugh again.” This word is a combination of “fake” and the Yiddish word fakakta, meaning “ridiculous,” especially in behavior.

5. Gnoshaholic n. A person who can’t stop nibbling on food for virtually the entire day. As many of you know from our sister site, the Nosher, the word nosh (which is spelled here as “gnosh”) means “to nibble.”

6. Hotzeplotz phase n. A period of life when a person feels lost and aimless, often experienced by young people just out of college (or many of us living through a pandemic). Hotzeplotz is the Yiddish word for “the middle of nowhere.”

7. Kvellkill v. To brag so much and so often — particularly about one’s children — as to completely bore the listener. Since you are arriving at this article at Kveller (welcome!), you are likely aware that kvell is Yiddish word that means “experiencing pride for someone else, in particular one’s children.” Combined with the word “buzzkill,” kvellkill is kvelling taken too far. (Note: Determining when this happens is open to interpretation!)

8. Machatunausea n. The feeling of revulsion one feels at having to spend time with the parents of your child’s spouse. The origins of this word is the combination of nausea with the Yiddish word machatunim, which means the “parents of your daughter or son-in-law.” While holiday gatherings may normally inspire these feelings in parents with married children, we’re guessing that one bright spot of the pandemic is that machatunausea is lessened over Zoom.

9. Mini-megillah n. A post on social media that is too long to keep its reader’s attention, like a Twitter thread that just goes on and on. This term stems from the Yiddish word megillah, which means “long and tedious story.”

10. Patshke disorder n. A neurotic condition of culinarians who endlessly mess around in the kitchen, without ever getting the meal on the table. This disorder invokes the word patshken, which means “to dawdle or mess around unproductively in a room of the house” — particularly the kitchen.

11. Polischmerz n. The quality of having a dismal or depressing view of the national or world political situation. (Which just about everybody has these days!) This originates from the Yiddish word schmerz, meaning “pain,” which comes directly from a German word of the same meaning.

12. Schmatta-chic: a. The quality of a person who wears worn or old clothes as a fashion statement. Klein notes that this compound word is derived from shabby-chic, or the concept of wearing worn-down clothes as a fashion statement. Schmatta is the yiddish word for “rag.” Hence, schmatta-chic. Fun fact: this is Klein’s favorite of the words: “It’s the sound of it that gets to me.”

13. Schmendrink n. A ludicrous, super-sweet cocktail. (Think a mix of ginger liqueur and raspberry-lime sorbet.) Schmendrink combines the word drink with the Yiddish word schmendrick, meaning “fool.”

14. Slapshtick n. Old-fashioned and long-winded humor. For example, the endless, detailed jokes told at Catskills resorts in the mid-twentieth century. Klein gives the example: “Uncle Morty is doing his after-dinner slapshtick again.” Klein notes that this combination of slapstick humor and shtick, meaning a person’s particular interest or comedy, is “kinda fun, if you have a spare hour or two.”

Header image design by Grace Yagel