In college, I had a professor tell me that no one ever lost their mind over a war, but over a broken shoelace. This concept basically boils down to how much we ask of ourselves. We tell ourselves that we can deal with something truly horrible — a war, say, or a global pandemic — just please don’t add on one more thing, lest we fall apart.

This idea has stuck with me ever since, and has proven to be one of the truest things I have known. In my own worst, most harrowing moments — staring at a mass on a scan of my mother’s pancreas in the middle of a routine doctor’s appointment — I have gritted my teeth and squinted out at the world, and done that thing we do, that trance-like, meditative work of getting to the other side, only to stub my toe on the way to put away laundry and fall apart in a pile of clean socks.

This toe-stubbing is what the past nine months have felt like for a lot of people. Not the people who have suffered in giant and terrible ways — as so many have — but the rest of us. For millions of us across the country, we have done this big work together. We have hunkered down; we have heard the sirens of too many ambulances; we have had holidays and board meetings and therapy via Zoom; we have written postcards to voters; we have skipped summer camp and become camp counselors ourselves; we have become at-home educators, activists, and leaders. We have scrambled for cleaning supplies; we have donated to good causes; and we have watched an endless loop of Tik-Tok outtakes, guest-starring in too many, even.

Some of it hasn’t been terrible. There has been delirious laughter; bonding over baking triumphs and failures; long walks and so much fresh air. In my suburban New York town, we have built an entirely new “hybrid” way of going to school, and despite some bumps, it more or less works. Some kids go to school on some days, other kids go on others. It’s not perfect but the kids are learning and growing. These days, the train station has a few more cars in its parking lot than in the spring, because some people have gone back into their offices and some back to the orthodontist. In other words, while Covid-19 remains a serious threat, we are moving along.

But sometimes — say, when there is a glitch with the WiFi at our house — I feel the frustration start to boil over. Sometimes, a school-supplied Chromebook freezes in the middle of a big test. Sometimes, someone can’t hear what the teacher said or someone missed out on weekend plans made at school. Sometimes, someone sat next to someone who was diagnosed with Covid. Sometimes, someone has to quarantine and look out from his window on a warm fall day and miss out, and miss out, and miss out. We have sent kids off to college — only to have them hole up in single dorm rooms, alone and far from the home that so recently supplied them with safety and extraordinary togetherness, just when they were supposed to want more freedom and less safety. We have swapped hugs for elbow bumps; kisses for waves; and we have stopped breathing near each other when what we need most is someone else’s breath in our ear.

As the pandemic continues, there is so much missing out. None of it seems so important in the scheme of things — nothing is too much when we have our health, when we have food, when we have each other. Of course. But I am finding that some days, these little things pile up and become too much to handle.

I continue to try to be a writer, even as I study AP World History late into the night with my 15-year-old; even as I have to help (parent input encouraged!) my 13-year-old son build a globe out of a blow-up beach ball for Earth Science. (The assignment actually was supposed to involve a pumpkin, but in some strange twist of pandemic fate, pumpkins were sold out everywhere.) Nevermind the fact that the only reason I had said beach ball was because we recently threw a backyard bar mitzvah for said son, without many of the people we love most. Instead, we used blow-up beach balls to decorate the lawn, with the vain hope of filling the void left by our loved ones’ absence. Nevermind that we are one cold front away from needing less lawn care and way more art supplies.

These days, I am left wondering how — and when — all of these micro-stressors will abate. Will this happen one month after a vaccine is widely distributed? Will it be a year after? When will we dance and sing and sweat together again, and will we even like it when we do? Or will there be a strange nostalgia for the safety of our hermetically sealed lives?

There was a time, after the tragic Sandy Hook school shooting in December 2012, that I used to cry after my kids got out of the car and headed into their school building. After a while, I stopped actively crying — but I continued to store those tears in the back of my throat. They accumulate there, and I think this is what post-traumatic stress is — it’s not always trauma in the aftermath of one big, terrible thing, but an accumulation of small, terrible things piled up and carried around with us. There comes a point when there are just so many small, terrible things that, once one more thing joins the heap, it breaks us. This is the shoelace moment — not the months-long quarantine, but that moment in the car line when you are first sending your child back to the classroom, equipped with a gallon of Purell and thin piece of fabric, the only things protecting them from a perplexing and deeply scary virus.

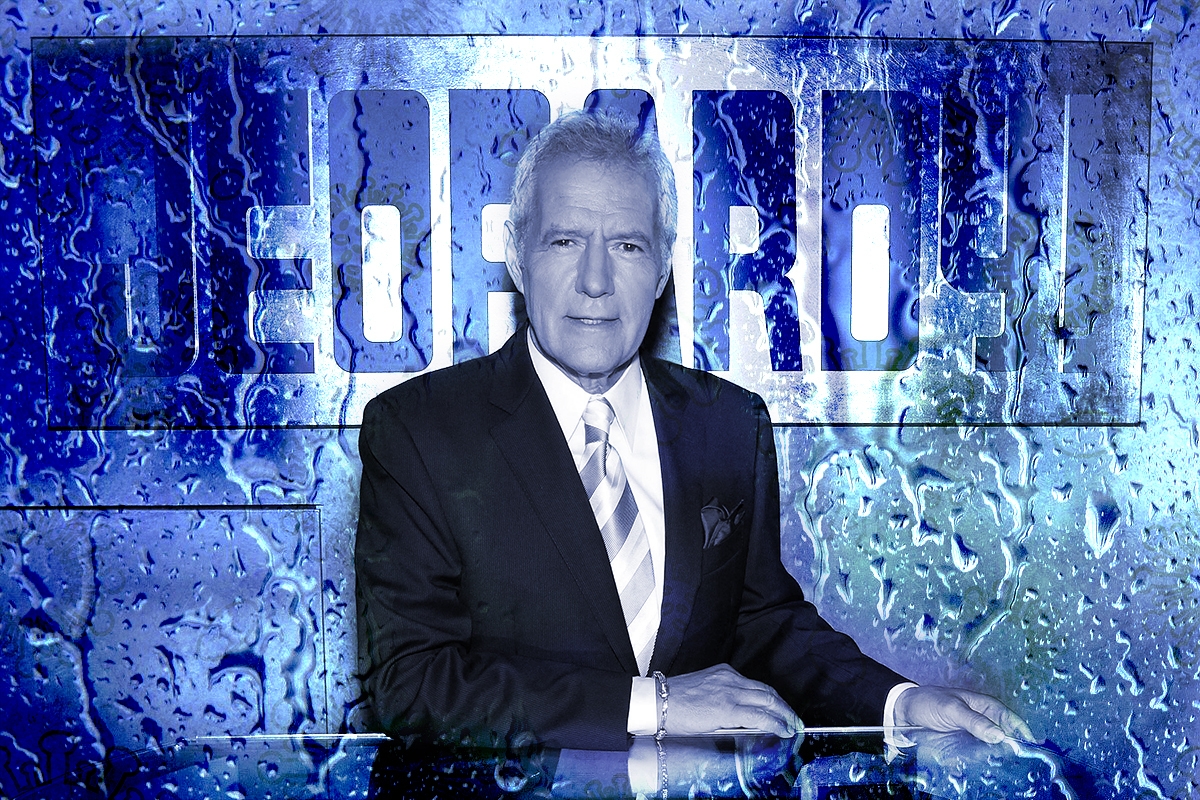

When Alex Trebek died on Sunday at age 80, it felt like an especially powerful loss for my family, considering that we sit and watch Jeopardy together every single night, spitting out answers in between forkfuls of dinner. When I heard the news, I once again cried in a new way. How would we go on without him? Yes, it’s a small thing for my family to lose him, when his own family has lost in such a big and personal way. But, when I found out, it was my one-thing-too-many, my broken shoelace after a war. I crumbled and, hands shaking, I called my brother, who cursed and then went silent on the other end. Like Trebek, our mother, ten years younger than Trebek, had died of pancreatic cancer — just six months before Covid-19 struck, when the global mood caught up to our personal mourning. She had followed Trebek’s progress closely. Irrationally, all I could think of in this moment was that she would be devastated. Broken.

One day, some day, we will view the pandemic in the rear-view mirror. But I, like the rest of us, will carry this time around with me into old age (God willing!). And so, when I one day stub a toe in the hallway after a harder-than-usual day, I might just say, I know this feeling. It is the shoelace breaking just when I was getting ready to lace up and go back out into the world. When that happens, just let me sit in the pile of socks for a second, and then I will get back up. Until then, I’ll take 2021 for $200, Alex.

Header Image by Frederick M. Brown/Getty Images