When I started translating Yiddish children’s literature seven years ago, I was thinking both as a language teacher and a mother. What could my second-semester college students realistically read in the original? Were there any authentic Jewish children’s stories that could take my children into the culture of their Ashkenazic ancestors?

Pressing questions of identity also loomed: Could I productively fuse my work as a scholar with my task as a mother? Could my career-long investment in Yiddish culture offer something immediately meaningful to the Jewish community beyond the walls of academia?

My answer to all of those questions converged on a comprehensive anthology of Yiddish children’s literature, which has nearly 50 pieces that I selected and translated. During the years I worked on this project, I went from having two boys, ages 9 and 5, to parenting a high schooler, a middle schooler, and a preschooler. I thought of my kids as a focus group, noting what hooked them or bored them. I envisioned all the contexts in which my book would eventually be used: story hours at Jewish libraries, Hebrew school classes, summer camps, and day schools.

But just as my book was getting ready to meet its public, the coronavirus hit. As a result, nearly every aspect of our lives have been altered, from our careers to our kids’ schooling to our Jewish communal life. And yet, one bizarre silver lining to this entire experience is that I’ve found new relevance in these classic Yiddish children’s tales. Now that we’re seven or so months into the pandemic — with no end in sight — here are some Yiddish kidlit lessons I’ve learned that are helping me through the chaos of pandemic parenting.

1. It really could always be worse.

I am at least seven minutes into teaching a seminar on Zoom when the students finally get it through to me that my headphones aren’t working — apparently the audio wasn’t on as I breezily took attendance, shared my screen, and launched an activity. So I take the headphones off — and a neighbor’s leaf blower immediately turns on.

Equanimity returns and we find our groove… until my 4-year-old starts screaming for me. In the best of times, working moms spend a lot of energy concealing the claims that our children make on us, even when we are perfectly up-front about their existence. So it’s reflexively embarrassing. No tushies of minors were broadcast across state lines; I’m probably not afoul of any actual laws. It’s just… well… it could always be worse, right?

Fortunately, you can’t dig very deep into Jewish history without appreciating the many comforts and protections we have to mitigate the risk and minimize the suffering that come with a dangerous pandemic. “The Mute Princess” by Zina Rabinowitz is set (somewhat unusually for a Yiddish story) in Casablanca, where a silent girl of extraordinary beauty is brought to the Jewish orphanage by a local Arab. Her inability to speak turns out to be a symptom of the PTSD suffered when her parents died in an unspecified epidemic. It’s a hopeful story of resilience, though, as the girl finds care and community, recovering her faculty of speech. The lesson here? When the toll of these days shocks us into silence, we can help each other regain our voices.

2. Involve your children in your political passions.

A friend recently sent me a button that reads “Shtimt!” — “Vote!” in Yiddish. Wearing it opened up a great conversation about voting, democracy, and whether or not the president is, in my 4-year-old’s lexicon, “a good guy or a bad guy.” I described some of the incumbent’s signature policies and recent remarks, and he drew his own conclusions.

Yiddish children’s literature arose as an artifact of Jewish cultural nationalism. It wasn’t shy about politics — and we shouldn’t be either. Khaver Paver’s 1935 stories about “Labzik: A Clever Pup” (aka “Leftist Lassie”) were distributed through the Yiddish school system of the communist-aligned International Workers’ Order. In “Labzik and the Strike,” the whole family accompanies Berl the (Sewing Machine) Operator to picket harsh working conditions that the sweatshop bosses have introduced. As parents, we should all be ready to explain to our kids the ideals undergirding our political leanings in age-appropriate language.

3. Empathy is everything.

With an eight-year age gap, there is blessedly little conflict between my middle schooler and preschooler. But after months without in-person socializing and only a thin door separating virtual middle school from free-form homeschool pre-K, even the mellowest of tempers can turn gruff by lunchtime. “What do you think your brother is feeling?” we ask each of them.

In just 29 words, the Polish-Canadian poet Ida Maze evokes the question of empathy in the relationship between an older and a younger child:

If you were me,

And I were you,

I’d be in

Your shoes.

I would be eight,

And four’s what you’d be;

So then would you

Play with me?

4. Children learn all the time, so try not to stress about school.

If our kids are awake, they are learning from us — and not just academic subjects. For example, having my sons at home is an opportunity for them to see me doing work that brings me joy and fulfillment. What’s more, they witness my partner creating space for me to teach and write and speak with friends. Because we are all responsible for detoxifying masculinity, it’s especially important to me that they learn by example to be caring husbands and equal parents.

Kids also need some space to learn on their own; when we’re all cooped up at home together it’s all too easy to swoop in and solve every problem. In Sarah Liebert’s tale “Moe and Nicky,” two boys work as assistants to itinerant fruit and vegetable peddlers. On a blistering July day, they risk scorn and dismissal by skeptical adults as they figure out for themselves how to secure water for the horses left in their care while the bosses cool off. It’s a reminder that if you’re busy with work, or you’re taking a few minutes for yourself, your kids will be just fine.

5. Children will have questions we can’t answer, and that’s OK.

In Judah Steinberg’s “Questions,” a little boy gradually comes to understand and interrogate his own privilege. Through posing a series of uncomfortable questions, he realizes that he benefits from all kinds of unseen labor, both from other people (the washerwoman, the carpenter) and animals (the cow, the mule, and so on). He finally poses the questions to his mother because, as he says, “a mother is the smartest thing in the world.” But even she cannot answer what amounts to one throbbing, existential “Whyyyy?”

“When I grow up,” the boy resolves, “I myself will find the answers to these questions!” That’s not a bad parenting outcome.

6. Tantrums are like weather systems; they pass.

Show me a home in which no door has been slammed or no curse word has escaped these past seven months, and I will show you where liars live. Moyshe Kulbak’s “The Wind that Got Angry” is a lyrical tale of a weary winter wind that cannot find a place to rest come spring. Cast out from every potential place of comfort, he retreats to a field and whips up a mad, gorgeous blizzard. Begged to desist by the single mother of two young children, the furious, desperate wind doubles down on his rage and shoves snow in her face. When she appeals again, the wind is finally appeased; the tantrum has spent itself. In other words, everything — both good and bad — comes to an end.

7. You’re doing better at this parenting thing than you think.

Things are incredibly tough now, but remember this: Every day that our kids have not been eaten by a bear, we are, in fact, #winning.

The Soviet Yiddish writer Leyb Kvitko built an entire career on portraying absent or incompetent parents; nobody could care as well for children, by his reckoning, as the Soviet State and its avatar, “Papa” Stalin. But even disastrous parenting mishaps can turn out cheerfully. As the title promises, “The Girl in the Mailbox” is the tale of a dad who takes his little girl along to mail a letter, and then absentmindedly chucks her into the mailbox instead. A disaster? Perhaps — but she has a fantastic time going along with the mail from Argentina to Poland and home again, where her father eagerly reclaims her. And hey, at least she can travel.

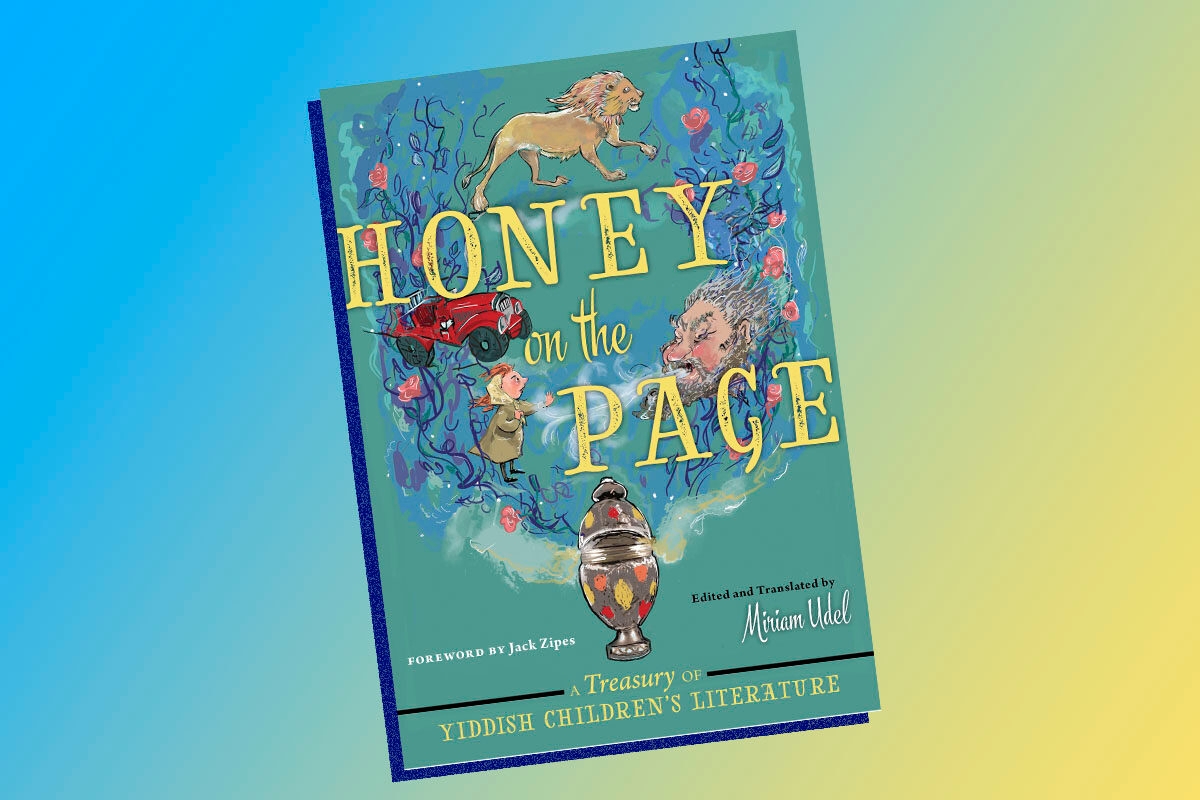

Header image via NYU Press