Five years ago, my grandmother passed away. She was like a parent to me, providing figurative and literal sustenance when my own parents could not. One of the ways she did this was through food, showing her love via the preparation of it: the cooking, the baking, and the presentation of it all.

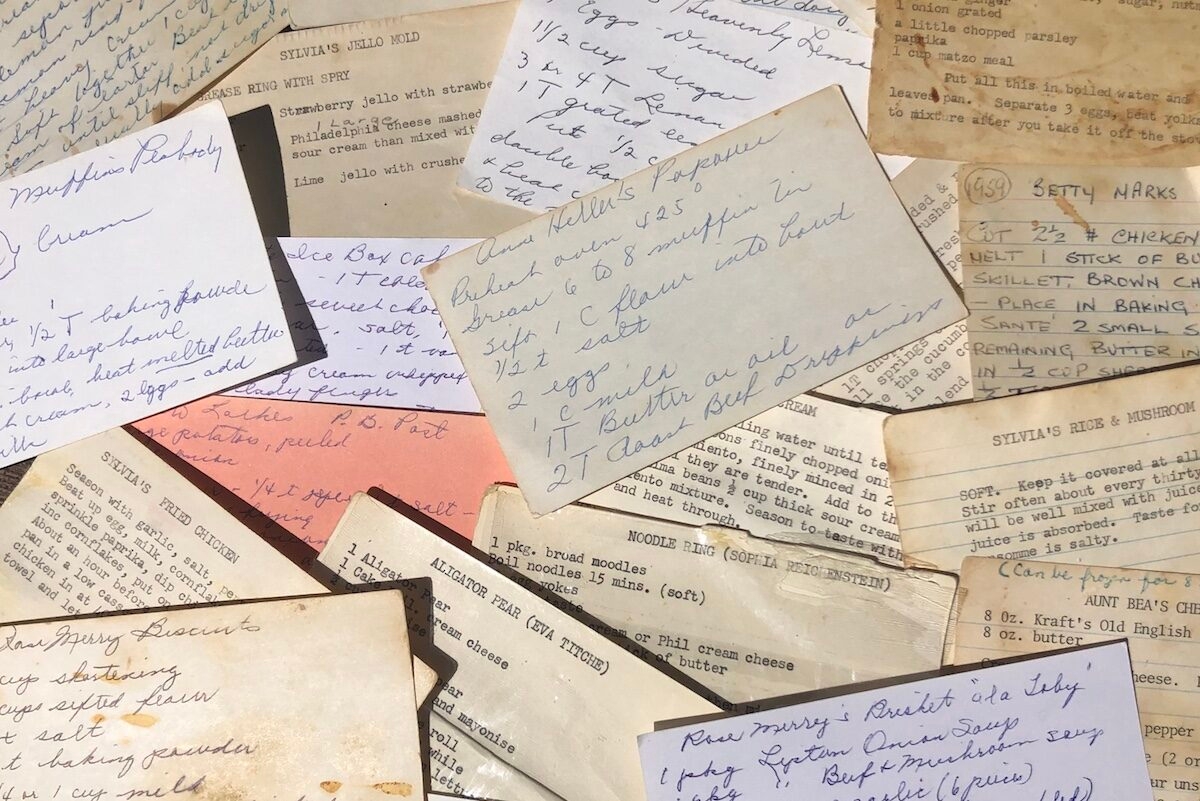

She kept her extensive collection of over 200 recipe cards in a Lucite box. She knew which color card went with what, and easily found what she was looking for. Years later, I am the proud owner of that recipe card collection.

I am generally the cook in my family, but in the “before times” we’d sometimes order in or go out to eat. This pandemic lockdown has given me fewer options, and now I’m cooking every breakfast, lunch, and dinner for my daughter, husband, and my mother, who is convalescing with us after a car accident.

A lot of people are embarking on projects these days. It makes sense, people aren’t finding entertainment outside of the home, and cooking is a multi-faceted form of entertainment: learning about or embracing cultures and heritage and feeding yourself and the people in your household. I like to cook, but continually having to produce culinary output is exhausting.

Turning to my grandmother’s recipe cards, however, has made this drab domestic task far more interesting. Over the course of our quarantine — and who knows, really, when things will truly get back to normal — I will try them all: two kinds of biscuits, matzoh balls, zucchini pancakes, and cheese straws, a cheddar cracker so delicate and rich the recipe calls for two sticks of butter.

The recipe cards are mostly on white index cards, with a few pinks and blues and the occasional neon in the pile. The bulk of them are discolored with age and smudged with unknown gravies and batters. Also in the collection are some recipes preserved from newspapers: Sauce Tomate from a 1980s New York Times article and one for French Dressing from the old Baltimore & Ohio Railroad. They are written in my grandmother’s competent cursive or typed via typewriter. They track her life journey from Memphis, where she was born, to New York where she raised her three daughters. The recipes include everything from dumplings and biscuits to “fancy” hors d’oevres fit for any respectable 1960s, dinner-party throwing housewife. (Our family photo albums attest to her talents at throwing such parties — for family, neighbors, and even the occasional foreign dignitary or celebrity.)

Passover falls in the early days of lockdown. We are not going to attend our family’s seder but I decided to make brisket, a dish that has brought my family together over countless meals. In a fashion that will be familiar to so many, the recipe in my grandmother’s collection says things like “add ketchup” — giving no indication as to how much — and “cook” providing no temperature or length of time. Also, we have no ketchup, though I find a bottle of Heinz chili sauce. So, in an amalgamation of my grandmother’s recipe and one I find online, I cook the brisket. When I serve it, my mother declares that it’s just like her mother’s. Success!

The next recipe I try is written on a sheet from my grandfather’s prescription pad: “Kisses or Meringues,” it reads, and the recipe is attributed to page 489 of The Settlement Cook Book, a cookbook created by Mrs. Simon Kander (actually Lizzie Black Kander, but you know, sexism) in Milwaukee in 1901 to help recent immigrants from Europe — mostly Jewish — become more “American.” My own copy of this cookbook is a 1941 edition that belonged to my grandmother. It has a floppy spine and is missing its cover.

Meringues were a mainstay at my grandmother’s house. She would make them and hide them in the laundry room or on top of the fridge. I found them, always, and ate at least five before the meal even began. “This is why we hide them from you,” she would say, and usually handed me a few more.

One dreary Seattle lockdown day, I pull out the Kitchenaid, something that always reminds me of my grandmother. I see my face reflected in the metal bowl and think of tongues scraping cookie dough off spatulas, fingers trailing in the sugary egg mix, my grandmother playfully swatting my hand away with a wooden spoon.

I’ve failed at this recipe before — whipping the egg whites, you have to get the consistency just right — but on this afternoon, my daughter and I produce perfect dollops of meringue. They are gone in a day.

My next attempts were popovers, which reminded me of trips to Neiman Marcus with my grandmother. This experience always felt very posh to me: I always wore my fanciest shoes. I still remember the squeak of patent leather on shiny floors and the smell of perfume wafting on the first floor. But eating at the cafe was the highlight of the trip: They served guests espresso cups of chicken consommé and a basket of popovers with strawberry butter. The popovers were still steaming; we broke into them quickly and asked for more.

Only later, as an adult, did I realize the reason she spent so much time with me and lavished me with these tiny luxuries. Her aim was to take me out of my house, which was a home filled with abuse and neglect. These journeys into a different world, these bites of food, her crow-footed eyed smiles — these were part of her plan to love me and love on me, because I got so little of it at home.

It worked. Popovers, of all foods, of all the dishes among her recipe cards, say “love” to me. Their crunchy exteriors and their airy, eggy insides are an indication that there can be significant differences between what’s outside and what’s in, between what we show people and what we keep hidden inside.

At least half of my grandmother’s recipes are attributed to friends and family: Aunt Bea, Rose Merry, Sophie Reichenstein, Eva Titche, Betty Marks — mostly Jewish women I’d heard of or knew, though some remain a mystery. On my grandmother’s popover recipe card — which is credited to her friend Anne Heller, and not Neiman Marcus — wet flour splotches cover the oven temperature. I look it up online and settle on 425 degrees. I mix all the ingredients in a blender, but leave out the roast beef drippings because I don’t have that on a random Monday morning.

After forty minutes, I pull them from the oven. I haven’t used enough grease, and the popovers stick in the muffin tin. “It’s OK!” my daughter says when she sees I’m near tears. “What matters is you tried.”

The earnestness in her face brings me back to the present. We eat the popovers, still warm from the oven, with our fingers. We spread homemade strawberry butter on it and it’s… not great. They are a little dry, and crumbly where we had to pull them from the edges of the tin. They are so far from the experience I remember at Neiman Marcus, and yet, in my daughter’s blue eyes, I see my grandmother, whose eyes were the same color. She would be pulling scraps from the tin and laughing along with us.

Aunt Bea’s Cheese Straws

My grandmother made these cheese straws for every dinner party and holiday meal that I ever attended. Despite the ingredient list, they are not heavy — cheese straws are delicate and somewhat soft cheese crackers, like high-end Cheez-its. I do not know who Aunt Bea is, but I thank her often for this recipe.

Ingredients

- 8 oz. sharp Cheddar cheese

- 2 softened sticks of butter

- scant pinch of salt

- 4 dashes of cayenne pepper

- 2-3 dashes of Tabasco sauce

- 2 heaping cups of flour, unsifted

Directions

1. Pre-heat oven to 350 degrees.

2. Cream butter and cheese.

3. Pack mixture into a cookie press (choose ridged attachment).

4. Push mixture into lines on greased or parchment lined cookie sheet.

5. Bake for 8 minutes.

6. Remove from cookie sheet while still hot.

Can be frozen for 8 months.

Image via Jennifer Fliss