An Alma Har’el show is a dream, and I mean that in every sense of the word. The Israeli director of “Honey Boy” and “Bombay Beach” turns 1960s Baltimore into a fantastical dreamscape in her first TV series, “Lady in the Lake.” The show is funny and uncanny and otherworldly, and also deeply grounded in the city and its history; the first two episodes are out today on Apple TV+.

Nobody marries reality and dream quite like Har’el. Every scene has a bit of both. From the city’s Thanksgiving Day parade, to a local pet shop central to the story, to the bar and the homes of the show’s heroines, every place is full of details that both ground it and make it look a little fantastical. Har’el even does that with the period aspect of the show — it feels both meticulously researched (Har’el asked her costume designer to look at photos of Jewish and Black women from 1960s Baltimore for inspiration) but also incredibly fresh and new.

“Lady in the Lake” is also a dream come true in other senses. It’s the first TV show starring Natalie Portman, and those who know about the actresses’ roots (her own directorial debut was an adaptation of Amos Oz’s “A Tale of Love and Darkness”) will find another layer of magic in the fact that the role is so complexly Jewish. Maddie Schwartz is a woman at a crossroads: She leaves her husband, Milton, to chase her dream of becoming a journalist. She is singularly resolved to find fame and success as a writer by unearthing the mysteries behind two very different local deaths: that of a young Jewish girl from her community, Tessie Durst, whose body she finds in the woods and that of a Black mother found in the lake, Cleo Johnson. Johnson, who becomes known as the titular lady in the lake, is the other heroine of the show and helps narrate both her and Maddie’s story. She’s played by Baltimore native Moses Ingram, who is stunning in the role.

Har’el beautifully weaves Maddie’s complex Jewish world, both literal and emotional: the way she connects with being the descendants of survivors, the way her local Jewish community shapes her life, the way antisemitism touches it, but also her relationship to white privilege. A straw that breaks the back of their marriage is Milton’s reaction to her using dairy dishes for the lamb; she finds Tessie’s body after being rejected by the synagogue’s search patrol for being a woman. And scenes of Jewish Baltimore, a kosher butcher and a Jewish funeral all have that same sense of eeriness and grounding.

“Alma really embraced fantasy and dreams in this series,” Portman shared in a press release. “It’s a beautiful way to get into the consciousness of these characters, to have these surreal moments. The show-stopping sixth episode, for instance, takes place entirely in Maddie’s head… She solves things in these fantasy sequences, too. They are very much her brain putting things together, subconsciously. You can see that she has these instincts that help her, or at least she thinks help her, to solve the mystery.”

Portman, who served as co-executive producer of the show, calls her director “a force” — Har’el had her hand in almost every part of the creative process, from co-writing the script to directing every episode and show-running all seven of them, too, her vision was clear and exacting.

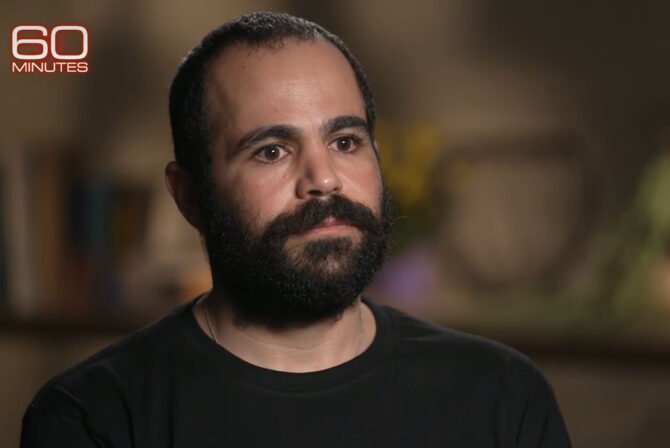

Alma Har’el looks dreamlike herself when I talk to her over Zoom, with her iconic mane of red hair on display, a gold chain on her neck and a jacket with hand-painted drawings of iconic cartoons. She’s sitting in front of a virtual background of Maddy’s own living room wallpaper, a densely painted forest. Ours is a short conversation, blanketed in Hebrew phrases of “how are you” and “thank you so much.” Just like I do when watching the show, I feel a little unmoored from reality in the most wonderful way.

I read that it was your first time directing in Hebrew.

Yes, it was, really was my first time directing anything scripted in Hebrew. My first film was done here in the U.S. and I never directed in Hebrew before. So I now have Natalie Portman, the incredible Natalie Portman, to thank for that.

That’s so exciting. And it’s also your first very Jewish project in a way. What was it like portraying this Jewish community of 1960s Baltimore? What was it important for you to show?

It was important for me because I feel like the we obviously live in a really challenging time. Not that it’s ever been an easy time to be Jews. But I think that there is a duality to our existence, especially Ashkenazi Jews, you know, who at once can be easily discriminated against and persecuted, and then at the same time, can, as a result of surviving their circumstances and assimilating, can become persecutors or oppressors. So, understanding that dualism and understanding the challenges that it comes with, but also the awareness that it can bring to human nature — not just as Jewish folks, but across the border — what we’re seeing around the world right now, the fragmentation that happens as a result of it. So all of that is fascinating to me and hopefully I captured some of some of that, and more.

Yeah, you really did. It was amazing. I had so many feelings watching the show… There’s this scene later on in the show — I don’t want to spoil it though we do see it briefly in the trailer — where Maddy wears a yellow star patch, the same one Jews wore in the Holocaust. We know that her mother lost her own mother and sibling in the Holocaust. Then there she is with this yellow star in this dream scene, as a chorus sings “Let My People Go…” It gave me goosebumps. What made you decide to dress her like that in the scene?

I think not a lot of people would notice it, but when Maddie is working for this newspaper, at a certain point on the show, without giving too much away, we see her, with her typewriter, and there’s three photos behind her on the wall taped to the wall: Barbra Streisand, Gloria Steinem and Anne Frank. And I think that those are her models of creativity and feminism. So I think that seeps into the sequence you’re speaking about, but if you combine that with the song that’s playing, it’s a clue. You know, the whole show — and especially episode six [an episode that’s almost entirely a dream sequence] — a lot of it is kind of constructed of clues of who we are and how character is destiny.

Yeah, I loved it. I love that you show these different women chasing their dreams. What it meant to be a Jewish woman at that time is very different. We think of all the incredible feminist icons of that time — Streisand and Steinem — but it was still so hard to be a woman with a dream.

It was incredibly challenging. I really was shocked — and wrote it into the script — when I found out that a woman couldn’t buy a car without her husband’s signature, and things like that. It wasn’t that long ago.