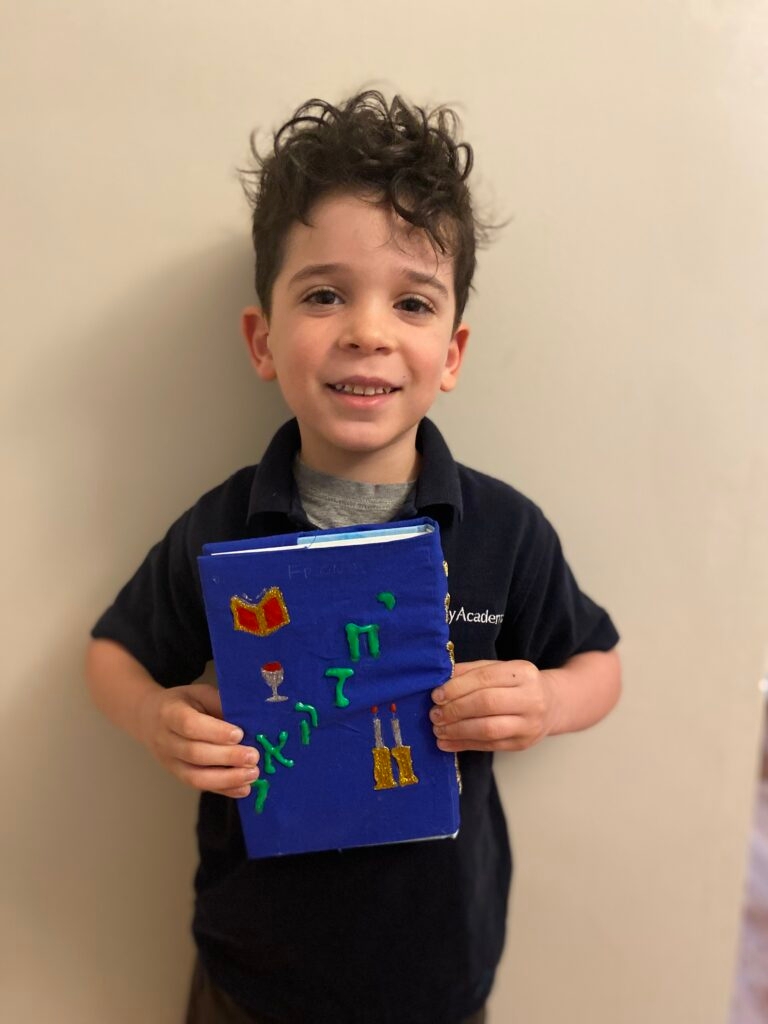

Sometime last May, my son brought home a package with a siddur — a Jewish prayer book — along with a blue hand-sewn cover and instructions. Celebrating the completion of the first year of elementary school by receiving a personalized siddur is a ritual common in Jewish day schools. My Facebook feed was filled with pictures of smiling parents at such events. We had until the end of May to decorate our child’s siddur, write a dedication and take a photo of our child with their new, adorned prayer book.

My mind immediately went to the siddur that I had received at Jewish day school back when I was in grade one. Unlike my son’s new siddur, filled with pictures and spiritual stories, my siddur had a no-frills brown cover, with gold Hebrew letters stitched on the side. I came home with instructions to cover my siddur so it would be protected from the wear and tear of daily use.

My siddur was expertly covered with wrapping paper that was found around the house. As the protective cover fell off, I’d absentmindedly trace the gold letters on the spine. I remember looking at other classmates’ more elaborate siddur covers, compared to my utilitarian wrapping paper. I remember a classmate of mine, the type who always had a full candy bar and a thermos of warm food in her lunch, whose cover featured beautifully designed embroidery. It was everything that mine was not — the type of siddur that a person with a chocolate bar in her lunch deserves.

That day my son brought home his new siddur, I was determined to be the mom who made him the perfect cover.

Fortunately, at the beginning of the pandemic, I had taken up embroidery. In March 2020, I was a stay-at-home mom with a 9-month-old and a 3.5-year-old and a partner who continued to work outside the house. I was stuck in a small apartment, with two small children each on different nap schedules, nowhere to go, nothing to do but look at each other. I know there were people who had it worse than me, but in my isolation it felt like my world was crumbling around me. I needed something to do beyond struggling to survive the day.

My Instagram feed started showing me sponsored embroidery tutorials. My boredom led me to believe that embroidery might be something I would want to try. I found an independent knit shop that had embroidery kits and somehow justified spending $70 on one. As soon as the kit was delivered to my door, I had a new hobby.

I immediately fell in love with the craft. It got me off my phone. It gave me a goal. There was something methodical and calming about stabbing a piece of stretched fabric over and over again. It was like beating on a drum. It gave me a new reason, other than being riddled with anxiety, to stay up until 3 in the morning.

A few months later, in June 2020, we decided to risk taking our children on a plane so that I could say goodbye to my dying grandmother — one of the women who raised me. Upon arriving, my family, which included my twin sister and her baby who had been born weeks before lockdown, was subjected to a strict two-week quarantine. Embroidery helped me count down the days until I could visit. It was a meditation that allowed me to hope I’d be given the chance to say goodbye.

And I did. After two weeks, with tears and trepidation, we went into the assisted living home. My grandmother had a good day. We were the daughters of the child she had lost too young. She always gave us her best self.

She died on the first night of Rosh Hashanah that year. COVID regulations required us to watch her funeral through a live stream. We decided to move back to my home city a few months later.

As new strands of COVID hit our new home and we were forced to quarantine once again, out came my embroidery kit. This time, rather than finishing any pieces, I created, then unraveled, each piece, taking more catharsis in the destruction than the creation.

Once we emerged, I packed away my thread and needles. The neatly organized rainbow of threads reminded me of the pandemic, the feeling of sickness in our body and of waking up every morning wondering if we would be able to see my grandmother before she died.

But when my son announced he would be bringing home his siddur cover to decorate, I felt determined to bring out my embroidery kit once again.

My son and I decorated most of the siddur cover with puffy fabric paint. (Well, at first it was my son and I, then he quickly got bored and went to do his own thing.) He insisted that I copy the design he brought home, which he had made in school. The puffy paint was quick to apply; mistakes were easy to fix. I was done in less time that I thought. But I wanted to sew his name on the spine of the cover as well, a trickier and more time-consuming task. The flimsy nature of the fabric meant I could not make a mistake and the thick coarse gold string meant the process would be finicky, and the thread tangle easily.

Every day my son asked me if I had started to sew his name on his siddur. I always replied that I had run out of time that night and would do it the next night. I finally started to sew on a day my son was home from school. It was Friday, due on Monday, and sewing was more appealing than playing or reading him another story. As I touched the gold thread against the fabric, I was taken back in time. I felt my hands on my own brown siddur with the gold writing. And then I had a flashback. One that I had not thought of in years and could not shake from my head until I wrote it down, and then for weeks afterwards.

In the months leading up to my older sister’s bat mitzvah, there was a loom on our dining room table. My mother, and the other women in her sisterhood group, had purchased looms to weave tallits and kippahs to gift to their daughters for their bat mitzvahs — religious garments that my mother and her friends were not given the opportunity to experience themselves.

I thought about how that loom sat on the dining room table as the tallit grew inch by inch. Then the loom sat on the table untouched after my mother suddenly died weeks before my sister’s bat mitzvah. Somehow, the tallit got finished and my sister wore it as we managed to celebrate her rite of passage.

At my own bat mitzvah, there was no loom on the table. There was no one to hand weave a tallit. But my grandmother crocheted the kippah I wore on the bimah. And my aunt, my mother’s sister, decorated a stuffed bear that wore a matching tallit and kippah.

It was those memories that weaved in and out as I fought with the string to create the letters of my son’s Hebrew name. I was sewing the letters and connecting myself to the work the women before me did, to create a memento for my firstborn. The string connected me to generations past and future. To my grandmother who knit me mittens, hats and blankets every winter to keep me warm. To the loom that sat on my dining room table, untouched after my mother’s premature death. As I handed my son his siddur, with his name hand-stitched down the spine by his mother, he joined that chain, and felt the love of creation.