This week, I learned how to say “frustrated”in Hebrew (metuskelet). I also learned how to say “win” (menatzachat). In this mostly logical, often mind-boggling language, learning both words at the same time is not the least bit ironic. It makes perfect sense.

I signed up for Hebrew classes at the beginning of Covid. Having heard Mark Cuban, the Jewish entrepreneurial billionaire, speak about the gift of time, I decided to make the most of mine in isolation and learn a new language. I found Citizen Cafe, a Tel Aviv-based Hebrew language school focused on teaching conversational Hebrew, which offers online classes.

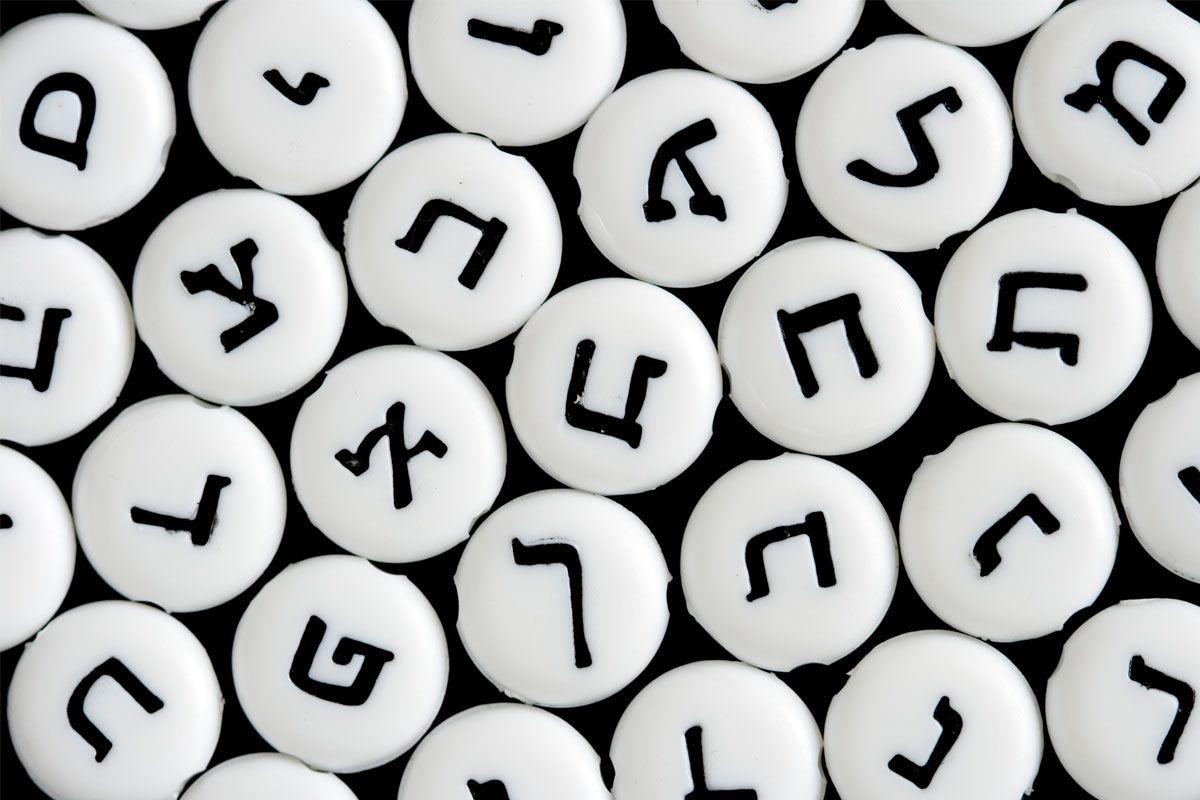

In the two years since I have fallen head over heels for this language that tortures me with its backward alphabet and right-to-left orientation. Its rolled Rs and guttural sounds ensure that even when I know the word, I won’t pronounce it correctly.

Hebrew is that cool, elusive kid. It marches to the beat of its own syntax. Unlike English, Spanish and French, which come from Latin, Hebrew is derived from, well, Hebrew. Originally a Biblical language that was primarily used for prayer and study, Hebrew was revived as a spoken language when Jews began arriving in Palestine. Eliezer Ben Yehuda, a Lithuanian who immigrated to Israel in 1881, is known as the father of modern Hebrew.

It is 8 a.m. on a Monday morning and Ori, my Hebrew teacher, starts the class with drills. I brace myself. This shouldn’t be hard, the questions Ori fires off in quick succession are all ones we have been practicing since the semester started five weeks ago. “Why don’t they live in the city anymore?” Ori asks. I know the answer, at least the individual words. “Because. They feel. Connected. To the Desert.” It takes me several tries to smash it together and blurt it out in rapid fire, like a true Israeli. I have come to learn that Israelis speak like they have just gulped down six espressos. There’s no slow Southern drawl or deliberate Midwestern speech cadence. Instead, every thought, every emotion is expressed in one run-on sentence. Hebrew is a work out. Ori’s expression brightens as he exclaims, “Exactly!”

I’m not sure why I’m spending so much time and money learning this language. Hebrew’s not exactly useful or spoken widely. But I was drawn to it. Perhaps it’s a do-over — a chance to undo my early years at a Hebrew day school, where I was uninspired by the Biblical Hebrew taught through Torah studies. Now I am learning conversational Hebrew, the living, breathing kind that is spoken in cafes and shuks. That’s spoken by Jews in Israel reinventing Middle Eastern cooking, creating critically acclaimed television and building life changing technology. Learning Hebrew isn’t bringing me closer to Judaism, but it is bringing me closer to Israel. And maybe that will turn out to be the same thing. Either way, I am all in.

I love that every Hebrew word has a secret — a three letter root that tips you off to the word’s meaning. So if you come upon a word you are unfamiliar with, like “to connect,” (lechaber) you can tell from its root (ח-ב-ר) it has something to do with relating to others/friendship. It’s like a linguistic GPS.

Recently we learned the word “to descend” (laredet). Its root (י-ר-ד) shows up when you are talking about the rain coming down (yored geshem) and when you are trying to download something (lehorid). It even shows up when you are talking about something of “lesser quality” (yarud). The root system enables Hebrew to push the boundaries of language in the most user-friendly way.

There is also a semantic precision to the language that delights my Type A personality. The word for knowing someone is totally different than knowing something. So in Hebrew, knowing David is different than knowing the standard deviation of five. In much the same way, having dinner at your boyfriend’s house is not expressed in the same way as having dinner at a restaurant. And going “outside” (hachutza) and standing “outside” (bachutz) are two entirely different things.

Many of the words, too, are like webs spanning entire ecosystems of meaning. The word “order” (seder) not only relates to an organization, but to tidy up (lesader) and a sequence (sidra). It is also the same word we use for the Passover ritual feast, which has a very specific order followed year after year.

There’s something freeing about knowing that I will never be great at speaking Hebrew; I can learn for the sake of learning. It’s empowering, too, to know that I have chosen to do something really hard. And I am doing it. I may always struggle with the word “frustrated” but I can say the word ”win” like I grew up in Tel Aviv. Even Ori is impressed. Maybe there is irony here after all.